Asthma in adults - InDepth

Bronchial asthma - InDepth; Wheezing - asthma - InDepthAn in-depth report on how asthma is diagnosed, treated, and managed in adults.

Highlights

Asthma Guidelines

The U.S. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma recommend:

-

Assessment and Monitoring.

Doctors should use multiple measures to determine a patient's current condition and future risk for worsening of condition. Even patients who show few daily effects of asthma may be in danger of a sudden worsening of symptoms. -

Patient Education.

Patients should be taught skills to self-monitor and manage asthma. Doctors should give patients a written asthma action plan, which includes information on daily treatment and ways to recognize worsening asthma. -

Control of Environmental Factors and Other Asthma Triggers.

It is important to reduce exposure to allergens. Treating co-existing chronic conditions (such as rhinitis, sinusitis, and obesity) can also help improve asthma control. -

Medications.

A stepwise approach is recommended where medication types and doses are increased or decreased based on the level of asthma control.

Exercise-Induced Asthma

A short-acting beta-agonist (like albuterol) is recommended as the first-line treatment for exercise-induced asthma. For patients whose symptoms continue, a leukotriene antagonist (like montelukast) is the second option, along with a daily inhaled corticosteroid.

Newer Medicines

Mepolizumab, benralizumab, and reslizumab are anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibodies. Omalizumab is an anti-IgE monoclonal antibody. These biologic drugs have been approved for use in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma, which is a type of asthma with increased levels of eosinophils (a type of white blood cell) found in the airways.

Introduction

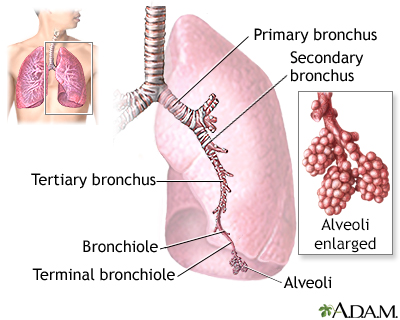

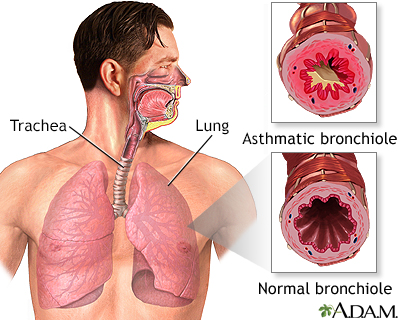

The word asthma comes from an ancient Greek word meaning panting. Essentially, asthma is an inflammatory lung condition that makes it difficult to breathe properly.When people inhale, the air travels through the following body structures:

- Air passes through the nose or mouth and then the pharynx (throat) into the lungs through progressively smaller airways called

bronchi

and thenbronchioles

. The lungs contain millions of these airways. - All bronchioles lead to

alveoli

, which are microscopic sacs where oxygen is taken in and carbon dioxide is expelled.

The major features of the lungs include the bronchi, the bronchioles, and the alveoli. The alveoli are the microscopic sacs lined by tiny blood vessels that take in oxygen and give up carbon dioxide.

Asthma is a chronic condition in which the airways undergo changes that are usually triggered by allergens, other environmental factors, or by infection. Asthma is characterized by two specific responses:

- The

hyperreactive

response (also called hyperresponsiveness) - The

inflammatory

response

These actions in the airway cause coughing, wheezing, and shortness of breath (dyspnea), the classic symptoms of asthma.

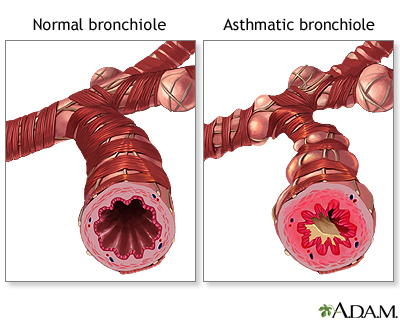

Hyperreactive Response

In the hyperreactive response, smooth muscles in the airways of the lungs constrict and narrow excessively in response to inhaled allergens or other irritants. This sudden contraction in the muscle walls of the bronchioles is called bronchospasm. Bronchospasms can result from many different health conditions (allergies, bronchitis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) but asthma is the most common cause.Everyone's airways constrict when exposed to allergens or irritants, but there are major differences in the hyperreactive response that occurs in people with asthma:

- When people

without

asthma breathe in and out deeply, the airways relax and open to rid the lungs of the irritant. - When people

with

asthma try to exhale, their airways do not relax and instead they narrow, causing hyperinflation of the lungs with unexpelled air. As asthma worsens, less air is able to get to the alveoli and the airways narrow further, causing patients to pant for breath. Smooth muscles in the airways of people with asthma may have a defect, perhaps a deficiency in a critical chemical that prevents the muscles from relaxing. And, during an asthma attack the airways narrow, making breathing difficult.

Inflammatory Response

Hyperreactivity is associated with the inflammatory response, which generally contributes to asthma in the following way:- In response to allergens or other environmental triggers, the immune system delivers white blood cells and other immune factors to the airways.

- These

inflammatory factors

cause the airways to swell, to fill with fluid, and to produce thick, sticky mucus. - This combination results in wheezing, breathlessness, an inability to exhale properly, and a phlegm-producing cough.

Inflammation appears to be present in the lungs of all patients with asthma, even those with mild cases, and plays a key role in all forms of the disease.

Causes

Doctors do not fully understand the causes of asthma. They believe the disorder is most likely caused by a combination of genetic (inherited) factors and environmental triggers (such as allergens and infections).

The Allergic Response (Allergens)

Nearly half of adults with asthma have an allergy-related condition, which, in most cases developed first in childhood. (In patients who first develop asthma during adulthood, the allergic response usually does not play a strong causal role.)

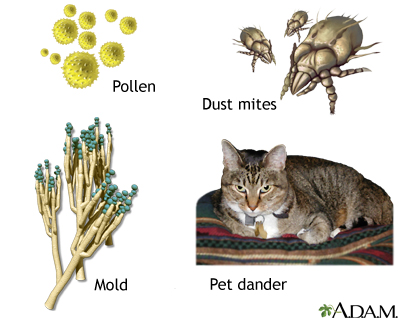

In people with allergies, the immune system overreacts when exposed to allergens. Allergic asthma is triggered by inhaling certain substances (allergens) such as:

- Dust mites, specifically mite feces, which are coated with enzymes that contain a powerful allergen. These are the primary allergens in the home.

- Animal dander. Cats harbor significant allergens, which can even be carried on clothing; dogs usually cause fewer problems. People with asthma who already have pets and are not allergic to them probably have a low risk for developing such allergies later on.

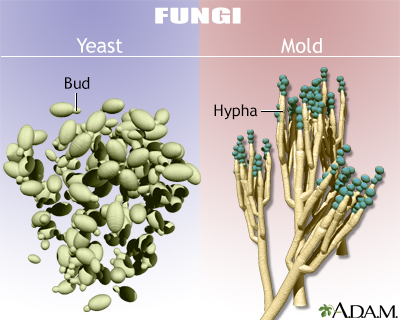

- Molds.

- Cockroaches. Cockroach dust is a major asthma trigger and may reduce lung function even in people without a history of asthma.

- Pollen from plants.

Environmental Factors (Irritants)

An asthma attack can also be triggered or aggravated by direct irritants to the lungs. Important irritants involved in asthma include cigarette smoke, indoor chemicals, and air pollution.

Infections

Respiratory viral and bacterial infections play a role in some cases of adult-onset asthma. In both children and adults with existing allergic asthma, an upper respiratory tract infection often worsens an attack.

Risk Factors

Sex

Before puberty, asthma occurs more often in males, but after adolescence, it is more common in females. In adults, women are more likely to report severe symptoms than men.

Hormonal fluctuations or changes in hormone levels may affect the severity of asthma in women. Many women with asthma experience fluctuations in severity that are associated with their menstrual cycle. Some women first develop asthma during or shortly after pregnancy, while others first develop it around the time of menopause (perimenopause).

Family History

Having a parent with asthma increases the risk of developing asthma by 3 to 6 times.

Race and Ethnicity

Non-Hispanic Black people have higher rates of asthma than non-Hispanic White people or other ethnic groups. They are also more likely to die of the disease. Race and ethnicity are, however, less likely to play a role in these differences in asthma prevalence than socioeconomic factors, such as having less access to optimal health care, and greater likelihood of living in an urban area (another asthma risk factor).

Allergies

People with allergic conditions like allergic rhinitis or atopic dermatitis have an increased risk of developing asthma.

Exposure to Environmental Factors

People who smoke or are exposed to secondhand smoke have an increased risk of asthma. Exposure to smog and air pollutants common in the urban environment and certain workplaces also increases the risk of developing asthma. [See "Causes" above.]

Obesity

Studies report a strong association between obesity and asthma. Evidence also suggests that people who are overweight (body mass index greater than 25) have more difficulty getting their asthma under control. Weight loss in anyone who is obese and has asthma or shortness of breath helps reduce airway obstruction and improve lung function.

Weight loss

An in-depth report on losing and managing weight safely for health benefits.

| Read Article Now | Book Mark Article |

GERD

Patients with asthma often also have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which is associated with acid reflux. It is not entirely clear which condition causes the other or whether they are both due to common factors. Acid reflux can worsen asthma symptoms. Treating GERD may help improve asthma control in some patients.

GERD

An in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of GERD.

| Read Article Now | Book Mark Article |

Aspirin-Induced Asthma

Aspirin-induced asthma (AIA) is a condition in which asthma gets worse after taking aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). AIA often develops after a viral infection. It is a particularly severe asthmatic condition, associated with many asthma-related hospitalizations. In about 5% of cases, aspirin is responsible for a syndrome that involves multiple attacks of asthma, sinusitis, and nasal congestion. Such patients also often have polyps (small benign growths) in the nasal passages. Patients with aspirin-induced asthma (AIA) should avoid aspirin and other NSAIDs, including ibuprofen (Advil and other brands, generic) and naproxen (Aleve, generic).

NSAIDs known as COX-2 inhibitors, such as Celexicob (Celebrex), are not associated with aspirin-induced asthma.

Prognosis

Doctors classify the severity of asthma into four groups (Intermittent, Mild Persistent, Moderate Persistent, and Severe Persistent) based on:

- Symptom frequency, ranging from fewer than 2 days per week to throughout the day.

- Nighttime awakenings, ranging from none to nightly.

- Short-acting beta2-agonist use for symptom control, ranging from 2 or fewer days per week to several times per day.

- Interference with normal activity, ranging from none to extremely limited activity.

- Lung function as measured by testing at the doctor's office.

- Number of exacerbations (sudden worsening) requiring oral corticosteroids, ranging from none to two or more in the last 6 months.

Persistent asthma is usually chronic, although it occasionally goes into long periods of remission. Long-term outlook generally depends on severity:

- In mild-to-moderate cases, asthma can improve over time, and many adults become symptom free.

- Even in some severe cases, adults may experience improvement depending on the degree of obstruction in the lungs and the timeliness and effectiveness of treatment.

- In about 10% of severe persistent cases, changes in the structure of the walls of the airways lead to progressive and irreversible problems in lung function.

Death from asthma is a relatively uncommon event, and most asthma deaths are preventable. It is very rare for a person who is receiving proper treatment to die of asthma. However, even when it is not life threatening, asthma can be debilitating and frightening. Asthma that is not properly controlled can interfere with school and work, as well as with daily activities.

Symptoms

Asthma symptoms vary in severity from occasional mild bouts of breathlessness to daily wheezing that lasts even when a patient takes large doses of medication. After exposure to asthma triggers, symptoms rarely develop abruptly but progress over a period of hours or days.

The classic symptoms of an asthma attack are:

Wheezing.

Wheezing when breathing out is nearly always present during an attack. Wheezing is a whistling sound caused by narrowed airways.Shortness of breath (dyspnea).

Shortness of breath is a major source of distress for patients with asthma. Breathing may be shallower and more rapid. Use of the muscles at the base of the neck and between the ribs may be more exaggerated than normal. Shortness of breath may worsen during exercise.Coughing.

In some people, the first (or only) symptom of asthma is a dry cough. Coughing may worsen at night or in the early morning.Chest tightness or pain.

Initial chest tightness without any other symptoms may be an early indicator of an asthma attack.

Not all patients experience the same signs or symptoms of asthma or experience them the same way.

The end of an attack is often marked by a cough that produces thick, stringy mucus. After an initial acute attack, inflammation lasts for days to weeks, even if it does not produce symptoms.

Symptoms of a Life Threatening Attack

The following signs and symptoms may indicate a life threatening situation:

- Rapid pulse

- Sweating

- Bluish skin color

- Anxiety or panic

- Grogginess, confusion, or difficulty talking

Asthma often progresses very slowly, but it may sometimes develop to a fatal or near-fatal attack within a few minutes. It is very difficult to predict when an attack will become very serious. Any symptoms that suggest a serious attack should be immediately treated with a rescue bronchodilator. If symptoms persist, call for emergency help.

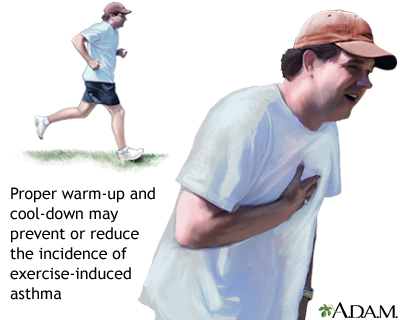

Exercise-Induced Asthma

Exercise-induced asthma (EIA), also called exercise-induced bronchoconstriction, is a limited form of asthma in which exercise triggers coughing, wheezing, or shortness of breath. This condition usually occurs during intense exercise in cold dry air. Symptoms start 5 to 10 minutes into exercise and then gradually resolve.

EIA is triggered only by exercise and is distinct from ordinary allergic asthma in that it does not produce a long period of airway hyperactivity, as allergic asthma does. Many people who have asthma also have EIA.

Nocturnal Asthma

Many patients experience a worsening of their asthma symptoms during the nighttime, especially during sleep. Attacks often occur between 2 to 4 a.m. Factors that increase the risk for nocturnal asthma include allergen exposure, sinus problems, GERD, chronic obstructive lung diseases, and the sleep-disordered breathing associated with obstructive sleep apnea.

Diagnosis

Your doctor will want to know any patterns or triggers associated with your asthma symptoms. Be sure to let your doctor know:

- Any possible allergic triggers.

- Whether symptoms are more frequent during the spring or fall (allergy seasons).

- Whether exercise, a respiratory infection, or exposure to cold air has ever triggered an attack.

- Any family history of asthma or allergic disorders, such as eczema, hives, or hay fever.

- Any occupational or long-term exposure to chemicals. If symptoms improve on weekends and vacation and are worse at work, the job may be the likely source of the asthma.

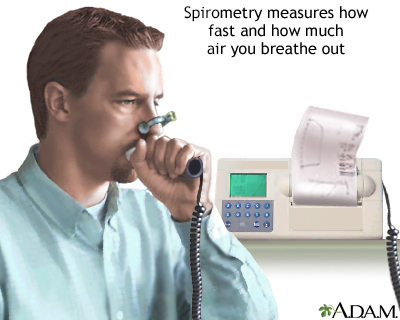

Lung Function Tests

If symptoms and a patient's history suggest asthma, the doctor will usually perform lung (pulmonary) function tests to confirm the diagnosis and determine the severity of the disease.A standard test uses a spirometer, an instrument that measures the amount of air taken into and exhaled out from the lungs. The patient breathes into a tube that is connected to a machine. The spirometer can give several measures of airflow:

- Vital capacity (VC) is the maximum volume of air that can be inhaled or exhaled, and is the total lung capacity (TLC). A spirometry test measures the forced vital capacity (FVC), as you breathe into TLC and then do a forced expiration to residual volume.

- Peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR), commonly called the peak flow rate, is the maximum flow rate that can be generated during a forced exhalation.

- Forced expiratory volume (FEV1) is the maximum volume of air expired in 1 second.

Spirometry is a painless study of air volume and flow rate within the lungs. Spirometry is frequently used to evaluate lung function in people with obstructive or restrictive lung diseases such as asthma.

If the airways are obstructed, these measurements will fall. Depending on the results, the doctor will take the following steps:

- If measurements fall, the doctor typically asks the patient to inhale a bronchodilator medication. This drug is used in asthma to open the air passages. The measurements are taken again. If the measurements are more normal, the drug likely has cleared the airways and a diagnosis of asthma is likely.

- If measurement results fail to show airway obstruction, but asthma is still suspected, the doctor may perform a

challenge test

. This involves administering a specific drug (histamine or methacholine) that usually increases airway resistance only when asthma is present, although some other conditions can cause false positive tests.

Allergy Tests

Your doctor may recommend skin or blood allergy tests, particularly if a specific allergen is suspected. Allergy skin tests may help diagnose allergic asthma, although they are not recommended for people with year-round asthma.

Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide (FeNO) Testing

Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) tests measure how much nitric oxide is in the air you breathe out. Nitric oxide (NO) is a gas that is considered to be a byproduct of inflammation in the lungs. FeNO can be used when there are doubts about asthma diagnosis in people ages 5 and older.

Ruling out Other Conditions

Many other health conditions have symptoms similar to asthma:

- Asthma and chronic obstructive lung diseases (chronic bronchitis and emphysema) affect the lungs in similar ways and both may be present in the same person. Unlike other chronic lung conditions, asthma usually first appears in patients younger than age 30 and with chest x-rays that are normal.

- Panic or anxiety disorder can coincide with asthma or be confused with it.

- Other conditions that must be considered during diagnosis are pneumonia, aspirin sensitivity, severe allergic reactions, pulmonary embolism, other lung obstructions, cancer, heart failure, tumors, psychosomatic illnesses, sarcoid, and certain rare disorders such as cystic fibrosis.

Treatment

General Approach for Treating and Managing Asthma

Asthma is often a chronic condition but you can effectively manage it by:

- Working with your doctor to develop a written Asthma Action Plan that addresses daily maintenance treatment, rescue medications, and what to do if your asthma worsens.

- Following appropriate drug treatments and making necessary lifestyle changes.

- Identifying and avoiding allergens and other asthma triggers.

- Doing regular self-monitoring at home, including tracking peak flow meter readings.

- Communicating regularly with your doctor.

Based on your age, symptoms, and asthma severity, your doctor will determine an individualized treatment plan. In general, doctors recommend a stepwise approach for treating asthma. Medications and dosages are increased when needed, and decreased when possible. Your record of peak flow meter readings can help your doctor manage your medications and make necessary adjustments.

These are the signs of well-controlled asthma:

- Asthma symptoms occur twice a week or less

- Rescue bronchodilator medication is used twice a week or less

- Symptoms do not cause nighttime or early morning awakening

- Symptoms do not limit work, school, or exercise activities

- Peak flow meter readings are normal or the patient's personal best

- Both the doctor and the patient consider the asthma to be well controlled

Treating Symptoms Versus Controlling the Disease

It is important to understand the difference between coping with asthma attacks and controlling the disease over time.

Medications for asthma fall into two categories:

Rescue (Quick-Relief) Medication.

Medications that open the airways (bronchodilators) are used to quickly relieve any moderate or severe asthma attack. These drugs are usually short-acting beta-adrenergic agonists (beta2-agonists) taken through an inhaler. Beta2-agonists and other rescue medications do not have any effect on the disease process itself. They are only useful for treating symptoms.Long-Term Control (Maintenance) Medication.

Long-term control medications focus on controlling the damaging inflammatory response associated with asthma and not simply treating symptoms. For adults and children over age 5 with moderate-to-severe persistent asthma, doctors recommend inhaled corticosteroids, which are sometimes accompanied by long-acting beta2-agonists when corticosteroids alone fail to control the disease.

Unfortunately, many patients do not understand the difference between medications that provide rapid short-term relief and those that are used for long-term symptom control. Make sure your doctor explains how to avoid overusing your short-term bronchodilator medications and underusing your long-term corticosteroid medications. The overuse of bronchodilators can have serious consequences, while not properly using steroids can lead to permanent lung damage.

Inhaler Devices

Most asthma drugs are taken through inhalers. The two basic inhaler devices are the metered-dose inhaler (MDI) and dry powder inhalers (DPIs). In a hospital setting, or when a patient cannot use an inhaler, a nebulizer may be used. A nebulizer is a device that administers the drug in a fine spray that the patient breathes in.

Metered-Dose InhalerThe metered-dose inhaler (MDI) is the standard device. It allows precise doses to be delivered directly to the lungs. The medicine is contained in a pressurized canister that is placed inside the plastic inhaler. MDIs are often used with a spacer, which is a tube that is attached to the inhaler. The spacer serves as a holding chamber for the medication sprayed by the inhaler. The spacer helps improve the ease and efficiency of medication delivery.

Dry Powder InhalersDry powder inhalers (DPIs) deliver a powdered form of beta2-agonists or corticosteroids directly into the lungs. Unlike an MDI, dry powder inhalers do not contain a propellant and do not require a spacer. Some patients find that they are more difficult to manage than MDIs.

Treatment of Asthma during Pregnancy

Guidelines from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) emphasize that most asthma medications are safe for pregnant women. The guidelines recommend that pregnant women with asthma have albuterol available at all times. Inhaled corticosteroids should be used for persistent asthma. Patients whose persistent asthma does not respond to standard dosages of inhaled corticosteroids may need a higher dosage or the addition of a long-acting beta-agonist to their drug regimen.

For severe asthma, oral corticosteroids may be necessary. The NAEPP notes that while it is not clear if oral corticosteroids are safe for pregnant women, uncontrolled asthma poses an even greater risk for a woman and her fetus. Pregnant women with asthma face increased risks for complications including pre-eclampsia (a condition associated with high blood pressure) and preterm delivery.

Treatment of Severe Persistent Asthma

Most patients with asthma respond well to standard medications, but a small percentage of people are treatment-resistant. In these cases, a doctor (preferably an asthma specialist) should confirm the asthma diagnosis and evaluate other conditions that might contribute to severe persistent asthma.

Diseases and lifestyle factors that can worsen asthma include rhinosinusitis, nasal polyps, obesity, smoking, obstructive sleep apnea, thyroid dysfunction, female hormonal fluctuations, and GERD. Medications such as ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, and aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can also worsen asthma. Addressing these conditions can help reduce asthma severity.

For patients who are not helped by high-dose inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta-agonists, guidelines recommend trying either:

- Omalizumab (Xolair) for patients where allergies play a large role in their asthma

- Mepolizumab (Nucala),benralizumab (Fasenra), or dupilumab (Dupixent) for patients with high levels of eosinophils

- Tiotropium (Spiriva)

Bronchial thermoplasty is an outpatient procedure approved by the FDA in 2010. It is reserved for select adult patients whose severe and persistent asthma has not been helped by inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta-agonist medications. The procedure uses radiofrequency energy to heat lung tissue and reduce the thickness of smooth muscle in the airways so that patients can breathe better. Current guidelines recommend against bronchial thermoplasty for most people with uncontrolled moderate to severe asthma due to the risks involved and the modest benefits. Some people who are willing to accept the risks may choose to undergo this therapy after consideration together with their health care provider.

Quick-Relief (Rescue) Medications

Quick-relief (rescue) medications work immediately to relax airways and quickly control acute asthma attacks. They are not useful for preventing attacks or controlling inflammation in the airways.

Short-Acting Beta2-Agonists

The standard quick-relief medication is a beta2-agonist inhaler. Beta2-agonists are bronchodilators. They relax and open constricted airways during an acute asthma attack.Specific short-acting beta2-agonists include:

- Albuterol (Proventil, Ventolin, ProAir, also called salbutamol outside the U.S.), is the standard short-acting beta2-agonist in the United States.

- Levalbuterol (Xopenex) is a newer type of beta2-agonist.

Short-acting beta2-agonists are usually administered through inhalation and are effective for 3 to 6 hours. They relieve the symptoms of acute attacks, but they do not control the underlying inflammation. They are used alone only for patients with intermittent asthma. Most patients with asthma use a beta2-agonist only for rapid symptom relief during an asthma attack, and use a long-term control medication to prevent attacks and reduce airway inflammation.

Side Effects of Beta2-AgonistsSide effects of all beta2-agonists may include:

- Anxiety.

- Tremor.

- Restlessness.

- Headache.

- Fast and irregular heartbeats. Notify a doctor immediately if this side effect occurs, particularly if you have an existing heart condition.

Beta2-agonists may have serious interactions with certain other drugs, such as beta-blockers. People with diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, hyperthyroidism, an enlarged prostate, or a history of seizures should use these drugs with caution.

Short-acting beta2-agonists become less effective when taken regularly over time, which increases the risk for overuse. Overdose can be serious and in rare cases even life threatening, particularly for patients with heart disease.

Oral (Systemic) Corticosteroids

Oral corticosteroids are generally used for asthma flare-ups that do not respond to inhaler medications. Common oral corticosteroids include prednisone, prednisolone, methylprednisolone, and hydrocortisone.

For asthma treatment, oral corticosteroids are typically used for short "bursts" of treatment lasting 5 to 10 days. In some severe cases, they may be used as maintenance therapy.

Short-term side effects of oral corticosteroids include mood changes and irritability, fluid retention and weight gain, and high blood pressure. Oral corticosteroids can cause severe side effects if taken for long periods of time. These side effects include cataracts, glaucoma, osteoporosis, diabetes, osteoporosis, susceptibility to infections, and other serious conditions.

If you need to take oral corticosteroids for more than 5 days, your doctor will gradually taper off the dose. Abruptly stopping oral steroids after using them for a prolonged period of time (30 days or longer) can cause withdrawal symptoms.

Anticholinergic Drugs

Two inhaled drugs, ipratropium bromide (Atrovent) and tiotropium (Spiriva), are bronchodilators that are not approved for asthma treatment but are sometimes used for this purpose. Ipratropium is used as a rescue medication. Tiotropium is being studied for use as a long-term control medication for patients with severe persistent asthma.

Possible benefits of anticholinergics include:

- They may be useful for certain older patients with asthma who also have emphysema or chronic bronchitis.

- Combining with a beta2-agonist might help patients who have not been helped by a beta2-agonist alone.

OTC Rescue Medications

Asthmanefrin is an over-the-counter (non-prescription) rescue bronchodilator that contains a form of epinephrine called racepinephrine. The medication is inhaled through an atomizer. Asthmanefrin came on the market in 2012 as a replacement for Primatene Mist. Primatene Mist was discontinued because its inhaler used chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) propellant. (CFCs are banned because of environmental concerns.)

Asthmanefrin does not use CFC. However, many doctors do not recommend the use of epinephrine products for asthma because the drug can raise heart rate and blood pressure, and may increase the risk for heart attack and stroke. In general, patients are much better off seeing a health care provider and using inhalers that are prescribed.

Long-Term Control (Maintenance) Medications

Long-term control (maintenance) medications are taken on a regular basis to prevent asthma attacks, control inflammation in the airways, and manage chronic symptoms.

Inhaled Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids, also called glucocorticoids or steroids, are powerful anti-inflammatory drugs. Steroids are not bronchodilators (they do not relax the airways) and have little short-term effect on symptoms. Instead, they work over time to reduce inflammation and prevent permanent injury in the lungs. They can also help prevent asthma attacks from occurring.

Taking a corticosteroid drug through an inhaler provides effective local anti-inflammatory activity in the lungs with very few side effects elsewhere in the body. (By contrast, steroids taken by mouth have considerable side effects throughout the body.) Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are recommended as the primary therapy for any patient needing long-term control medications for persistent asthma.

The most recent generation of inhaled steroids include beclomethasone (QVAR), budesonide (Pulmicort), ciclesonide (Alvesco), flunisolide (AeroBid), fluticasone (Flovent), mometasone furoate (Asmanex), and triamcinolone (Azmacort and others). These steroids are sometimes combined with a long-acting beta2-agonist in a single inhaler, such as budesonide-formoterol (Symbicort), fluticasone-salmeterol (Advair), or mometasone-formoterol (Dulera). Optimal timing of the dose is important and may vary depending on the medication.

Inhaled steroids are generally considered safe and effective and only rarely cause any of the more serious side effects associated with prolonged use of oral steroids. The following are possible side effects of inhaled steroids:

- Throat irritation, hoarseness, and dry mouth (the most common side effects). Using a spacer device and rinsing the mouth after each treatment can minimize or prevent these effects.

- Oral candidiasis (thrush). A yeast infection in the mouth, tongue, or throat may develop, especially if the mouth is not rinsed after use of the inhaled steroids.

- Rashes, wheezing, facial swelling (edema), fungal infections (thrush) in the mouth and throat, and bruising are also possible but not common with inhalators.

- Inhaled corticosteroids are associated with a higher risk for cataracts in patients over age 40, particularly with higher dosages. (No higher risk is observed in younger people.)

- Some studies report a higher risk for bone loss in patients who take inhaled steroids regularly, a side effect known to occur with oral steroids.

Long-Acting Bronchodilator Inhaled Drugs

There are two types of long-acting bronchodilators:

- Long-acting beta2-agonists (LABAs)

- Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs)

Long-acting beta2-agonists (LABAs) are bronchodilator drugs that help to open and relax the airways. Unlike the short-acting Beta2-agonists used for rescue medication, LABAs are used for long-term asthma control. They are not used for treating attack symptoms.

LABAs should never be used alone in the treatment of asthma in adults or children. They can be dangerous when used alone, because they can mask asthma symptoms, and they can increase the risk of asthma death unless paired with an inhaled steroid. LABAs should only be used in combination with another control medication, such as an inhaled corticosteroid. LABAs should be used for the shortest time possible, and should only be used by patients whose asthma is not adequately controlled by other asthma maintenance medications.

Patients may also benefit from as-needed LABA/ICS using formoterol as a LABA for symptom relief. Salmeterol-fluticasone (Advair), formoterol-budesonide (Symbicort), and formoterol-mometasone (Dulera) are long-acting beta2-agonists products combined with a steroid in a single inhaler that are used for treatment of moderate-to-severe asthma. The LABA-only versions of these drugs are salmeterol (Serevent Diskus) and formoterol (Foradil Aerolizer).

Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) are other long-acting bronchodilator drugs. Like LABAs, LAMAs are used to prevent asthma attacks rather than to treat attack symptoms. Also like LABAs, LAMAs are not used by themselves, but in combination with corticosteroids. Although LABAs are preferred over LAMAs when corticosteroids alone do not control asthma, if a LABA cannot be used or is not available, LAMAs can be used instead. LAMAs can also be used in addition to corticosteroids and LABAs when this combination is not sufficient to control asthma symptoms. Examples of LAMAs include umeclidinium (incruse), glycopyrrolate (Seebri), tiotropium (Spiriva) and aclidinium (Tudorza). Combination LAMA/LABA inhalers include umeclidinium/vilanterol (Anoro) and tiotropium/olodaterol (Stiolto).

Leukotriene Antagonists

Leukotriene antagonists (also called anti-leukotrienes or leukotriene modifiers) are pills that block leukotrienes. Leukotrienes are powerful immune system factors that, in excess, produce damaging chemicals that can cause inflammation and spasms in the airways of people with asthma. As with other anti-inflammatory drugs, leukotrienes are used for prevention, NOT for treating acute asthma attacks.

Leukotriene antagonists include montelukast (Singulair, generic) and zafirlukast (Accolate, generic). Zileuton (Zyflo) is a leukotriene inhibitor. These drugs may be used as second-line treatment for asthma control and are sometimes used for preventing exercise-induced asthma.

Side Effects and ComplicationsUpset stomach, headache, and sore throat are the most common side effects of leukotriene antagonists. Because zafirlukast and zileuton can raise liver enzyme levels, patients may need periodic liver tests.

In rare cases, leukotriene antagonists may cause mental health disturbances and behavioral changes. Mood problems include agitation, aggression, anxiousness, dream abnormalities, hallucinations, depression, insomnia, irritability, restlessness, tremor, and suicidal thinking. Patients who take a leukotriene antagonist drug should be monitored for signs of behavioral and mood changes. Doctors should consider discontinuing the drug if patients exhibit any of these symptoms.

Omalizumab

Omalizumab (Xolair) is FDA-approved for patients age 12 and older who have moderate-to-severe persistent asthma related to allergies. Omalizumab is a biologic drug that targets and blocks the antibody immunoglobulin E (IgE), a chemical trigger of the inflammatory events associated with an allergic asthma attack.

Omalizumab is given by injection every 2 to 4 weeks. It is used only to treat patients who have moderate-to-severe persistent asthma related to allergies whose symptoms are not controlled by inhaled corticosteroids.

Side Effects and ComplicationsAbout 1 in 1,000 patients who take omalizumab develop anaphylaxis (a life threatening allergic reaction). Patients can develop anaphylaxis after any dose of omalizumab, even if they had no reaction to a first dose. Anaphylaxis may occur up to 24 hours after the dose is given.

Omalizumab should always be injected in a doctor’s office, and health care providers should observe patients for at least 2 hours after an injection. Patients should also carry emergency self-treatment for anaphylaxis (such as an Epi-Pen) and know how to use it. With an Epi-Pen, or similar auto-injector device, patients can quickly give themselves a life-saving dose of epinephrine.

Anaphylaxis symptoms include:

- Difficulty breathing

- Chest tightness

- Dizziness

- Fainting

- Itching and hives

- Swelling of the mouth and throat

The FDA is currently reviewing whether omalizumab may be associated with increased risk for heart and vascular problems (ischemic heart disease, arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, and blood clots).

Anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibodies

Mepolizumab (Nucala), reslizumab (Cinqair), and benralizumab (Fasenra) are anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibodies FDA-approved for patients who have a high level of eosinophils. These drugs have been shown to reduce exacerbations in patients with severe asthma. They are not meant to be used in acute exacerbations or in patients with status asthmaticus.

Anti-IL-5 antibodies are administered once every 4 weeks and given either via subcutaneous injection or intravenous injection. Injections should be given in a provider's office and patients monitored for allergic reactions or even anaphylaxis. Some patients treated with mepolizumab (Nucala) have experienced opportunistic infections such as shingles or herpes zoster.

Theophylline

Theophylline is a bronchodilator drug. It relaxes the muscles around the bronchioles and also stimulates breathing. Since the introduction of inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta2-agonists, theophylline is not used as often for asthma treatment. It may still be used in some circumstances, such as for treating severe or nocturnal asthma. Theophylline is available in tablet, liquid, and injectable forms. Theophylline should not be used by people with peptic ulcers or GERD, and should be used with caution by anyone with heart disease, liver disease, high blood pressure, or seizure disorders.

Other Treatments

Immunizations

Patients with asthma should get an annual flu vaccine, and they should be vaccinated against pneumococcal pneumonia.

Annual flu vaccine

An in-depth report on the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of colds and flu.

| Read Article Now | Book Mark Article |

Treating Seasonal Allergies and Sinusitis

Patients with asthma and chronic allergic rhinitis may need to take medications daily. Patients with severe seasonal allergies may need to start medications a few weeks before the pollen season, and to continue medicine until the season is over. Treatment of allergies and sinusitis can help control asthma.

Allergies

An in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of common nasal allergies. Nasal allergies can be associated with sinus infla...

| Read Article Now | Book Mark Article |

Sinusitis

An in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of sinusitis.

| Read Article Now | Book Mark Article |

Immunotherapy ("allergy shots") may help reduce asthma symptoms, and the use of asthma medications, in patients with known allergies. They may also help prevent the development of asthma in children with allergies. Immunotherapy poses some risk for severe allergic reactions, however, especially for children with poorly controlled asthma.

Especially for children with poorly controlled ...

An in-depth report on how asthma is diagnosed, treated, and managed in children and adolescents.

| Read Article Now | Book Mark Article |

An oral form of immunotherapy that uses a sublingual (under-the-tongue) tablet has been researched. Recent reviews indicate that sublingual therapy may be helpful for milder asthma. However, this therapy has not been shown to improve more persistent asthma, and safety has not been well studied in patients with more severe asthma. Furthermore, many questions remain including dosage and duration of treatment. Sublingual therapy has recently been FDA-approved for allergic rhinitis caused by grass and ragweed allergies. At this time, sublingual immunotherapy is not approved or recommended for asthma treatment in the United States.

Preventing and Treating Respiratory Infections

Respiratory infections, including the common cold, can interact with allergies to worsen asthma. People with moderate to severe asthma are at increased risk of developing severe COVID-19 if infected.

People with asthma should try to minimize their risk for respiratory tract infections. Using alcohol-based hand rubs and washing hands are simple but effective preventive measures. Vaccinations for viral respiratory infections are also important.

Treating Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Asthma and GERD often co-exist. Some patients find that treatment of GERD helps improve their asthma symptoms. GERD treatment includes:

- Avoiding heavy meals and meals with fried food.

- Avoiding caffeine, chocolate, onions, and garlic.

- Avoiding eating or drinking at least 3 hours before bedtime.

- Elevating the head of the bed by 6 inches.

- Taking medications such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Be sure to talk to your doctor before taking these medicines. The use of PPI drugs to improve asthma symptoms is controversial. Studies indicate that these drugs do not help with asthma symptoms.

Managing Hormonal-Related Asthma

Women who suspect that menstrual-related changes may influence asthma severity should keep a diary of their menstrual dates and times of asthma attacks. Sometimes, adjusting medications in anticipation of menstruation may help prevent attacks.

Alternative Therapies

Many people with asthma turn to alternative therapies including high-dose vitamins (such as Vitamin D), homeopathic remedies, probiotics, isoflavone, omega-3 fatty acids, and herbal supplements. There is no evidence that any of these treatments are helpful for asthma.

However, because stress can worsen asthma symptoms and make breathing more difficult, alternative therapies that focus on relaxation and stress reduction may be helpful. These modalities include:

- Breathing and relaxation techniques, including meditation and yoga

- Biofeedback

- Hypnosis

- Acupuncture

- Massage therapy

Managing Asthma at Home

Asthma Action Plans

Asthma action plans create a written document for patients to manage asthma during stable times and to more easily identify when asthma is worsening. Important components of a home program include:

- A clearly written plan for taking asthma medications when condition is stable.

- Instructions for what medications to take if asthma gets worse.

- Education regarding the difference between long-term control medications and quick-relief medications.

- Monitoring of asthma on a daily basis. Symptom monitoring is adequate for patients with intermittent or mild persistent. asthma. Peak flow monitoring should be performed in patients with moderate or severe persistent asthma or those with a history of more severe exacerbations (sudden worsening or increase in severity of symptoms).

- A list of environmental control measures that need to be taken to control exposure to allergens.

- When to seek medical care.

Monitoring Peak Flow

A peak flow meter is a handheld plastic device for measuring peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR). PEFR measures how fast you can expel air out of your lungs and is an indication of lung functioning. Changes in the PEFR may indicate problems with asthma control even before symptoms appear.

It is a good idea to keep a written record of your peak flow meter readings. This data can help your doctor adjust medications and recognize problems before they become serious. Patients who self-manage their asthma with peak air flow measurements and appropriate medication use have fewer hospitalizations and unplanned doctors' visits, and generally have a better quality of life than those who rely only on the occasional doctor or emergency room visit to control symptoms.

To use a peak flow meter, stand or sit upright, set the meter to zero, take a deep breath and exhale hard and fast into the meter. Write down the number that appears on the meter.

Tips for regular peak flow monitoring include:

- Patients with severe asthma should take PEFR readings 2 or 3 times a day. The overall goal should be to achieve less than a 20% (and ideally only 10%) variation in readings between evening and morning rates.

- For mild-to-moderate asthma, a single reading each morning is usually sufficient, but check with your doctor.

- It is important to use the meter at the same times each day and to stand or sit in the same position to keep an accurate record.

- Keep an ongoing record of your readings to help detect any worsening of symptoms.

- Record any asthma attacks, exposure to allergens or triggers, and medications taken.

Peak low measurements are individually tailored to establish your normal range. Readings are then categorized as either being in the green, yellow, or red zone. Peak flows in the green zone are 80% to 100% of your personal best readings, readings in the yellow zone are 50% to 80% of your personal best readings, and peak flows in the red zone are less than 50% of your personal best readings. Patients should seek medical attention when their peak flows fall within the red zone.

Avoiding Environmental Triggers

It is important to avoid and control triggers that lead to asthma attacks.

Controlling PetsPatients who already have pets and are not allergic to them probably have a low risk for developing allergies. If pets trigger asthma, take the following precautions:

- If possible, keep pets outside.

- If this isn't possible, confine pets to carpet-free areas outside the bedroom. Cats harbor significant allergens, which can even be carried on clothing. Dogs usually cause fewer problems.

- Wash animals once a week to reduce allergens. Dry shampoos, available for both cats and dogs, can remove allergens from the skin and fur and are easier to administer than wet shampoos.

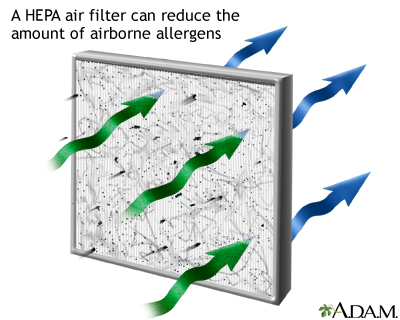

Spray furniture polish is very effective for reducing both dust and allergens. Air purifiers and vacuum cleaners with High Efficiency Particle Arresting (HEPA) filters can help remove particles and small allergens found indoors. Neither vacuuming nor the use of anti-mite carpet shampoo is, however, effective for removing mites in house dust. In fact, vacuuming stirs up both mites and cat allergens. If possible, avoid carpets and rugs.

A High Efficiency Particle Arresting (HEPA) filter can remove the majority of harmful particles, including mold spores, dust, dust mites, pet dander, and other irritating allergens from the air. Along with other methods to reduce allergens, such as frequent dusting, the use of a HEPA filtration system can help control the amount of allergens circulating in the air. HEPA filters can be found in most air purifiers, which are usually small and portable.

Bedding, Curtains, and Bedroom Environment- Replace curtains with shades or blinds, and wash bedding using the highest temperature setting.

- Encase mattress and pillows in special dust mite proof covers (synthetic pillows may pose a higher risk for asthma attacks than feather pillows, or no pillow at all).

- Wash pillows in water hotter than 130°F (55°C), or in cooler water with detergent and bleach.

- Wash sheets and blankets weekly in hot water.

- Avoid sleeping or lying on cushions or furniture that are cloth covered.

Living in a damp house is counterproductive. Dust mites thrive in humidity and damp houses increase the risk for mold. Humidity levels should not exceed 30 to 50 percent:

- Fix all leaky faucets and pipes, and eliminate collections of water around the outside of the house.

- Dehumidify basements, but empty dehumidifiers and clean them daily with a vinegar solution.

- Clean often any moldy surfaces in the basement or in other areas of the home.

- Avoid prolonged used of vaporizers to manage symptoms during asthma attacks.

Electric stoves and ovens are healthier than gas ones for people with asthma. Gas ovens release nitrogen dioxide, a substance that can aggravate asthma symptoms. Even smoky cooking can worsen asthma. Kerosene (used in space heaters and lamps) may also produce allergic reactions.

Exterminating Pests (Cockroaches and Mice)- Use a professional exterminator to eliminate cockroaches. (Cleaning the house using standard housecleaning techniques may not eliminate the cockroach allergens.)

- Exterminate mice and attempt to remove all dust, which might contain mouse urine and dander.

- Keep food and garbage in closed containers.

- Keep food out of bedrooms.

Cigarette smoke can accelerate the decline in lung function related to asthma. Even exposure to secondhand smoke can double the risk of an asthma-related emergency room visit. Everyone should quit smoking and encourage others around them to quit.

Smoking

An in-depth report on the health risks of smoking and how to quit.

| Read Article Now | Book Mark Article |

Avoiding Outdoor Allergens

- Avoid scheduling camping and hiking trips during times of high pollen count (generally, May and June for grass pollen and mid-August to October for ragweed in the eastern United States).

- Avoid strenuous activity when ozone levels are highest, which usually occur in early afternoon, particularly on hot hazy summer days. Levels are lowest in early morning and at dusk.

- Asthma attacks are often triggered by thunderstorms, perhaps because storms stir up pollen and spores or because of the build-up of ozone that accompanies such storms.

- Patients who are allergic to mold should avoid barns, hay, raking leaves, and mowing grass. Exposure to automobile fumes may worsen asthma. Fungi in car air conditioners can also be a problem.

- Air pollution can worsen asthma.

Exercise

Asthma is no reason to avoid exercise. Historically, about 10% of Olympic athletes have asthma. Some studies indicate that long-term exercise even helps control asthma and reduce hospitalization. Exercise can help control weight, which can help with asthma symptoms. Patients should consult their doctors before starting any exercise program, however.

People who enjoy running should probably choose an indoor track to avoid pollutants and to avoid cold, dry air in the cold months. Swimming is excellent for people with asthma. Yoga, which uses stretching, breathing, and meditation techniques, may also have particular benefits.

Hints for Reducing Exercise Induced Asthma (EIA)EIA occurs only after exercise and is more likely to happen during regular paced activities in cold, dry air. The following are some suggestions for reducing its impact:

- Warm-up and cool-down before and after exercise.

- Choose activities that do not require exposure to cold, dry air.

- Participate in activities with short bursts of exercise (such as tennis and football) rather than exercises involving long-duration pacing (such as cycling, soccer, and distance running).

- Breathe through a scarf or through the nose. This helps warm up the airways when exercising in cold air.

- Use any prescribed medications as directed.

Treatment guidelines for exercise-induced asthma recommend:

- A short-acting beta2-agonist (albuterol) taken 15 minutes before exercise is the first choice, and lasts for 2 to 3 hours.

- A leukotriene antagonist drug taken daily is the second choice for patients who continue to have exercise asthma symptoms. These patients should also use daily an inhaled steroid for maintenance control.

Resources

- American Lung Association -- www.lung.org

- American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology -- acaai.org

- American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology -- www.aaaai.org

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute -- www.nhlbi.nih.gov

- Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America -- www.aafa.org

References

Bardin PG, Price D, Chanez P, Humbert M, Bourdin A. Managing asthma in the era of biological therapies. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(5):376-378. PMID: 28463176 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28463176/.

Beasley R, Holliday M, Reddel HK, et al; Novel START Study Team. Controlled trial of budesonide-formoterol as needed for mild asthma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(21):2020-2030. PMID: 31112386 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31112386/.

Boulet LP, O'Byrne PM. Asthma and exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in athletes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(7):641-648.PMID: 25671256 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25671256/.

Boulet LP, Godbout K. Diagnosis of asthma in adults. In: Burks AW, Holgate ST, O'Hehir RE, et al, eds. Middleton’s Allergy: Principles and Practice. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 51.

Brozek JL, Bousquet J, Agache I, et al. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) guidelines-2016 revision. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(4):950-958. PMID: 28602936 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28602936/.

Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(2):343-373. PMID: 24337046 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24337046/.

Cloutier MM, Dixon AE, Krishnan JA, Lemanske RF Jr, Pace W, Schatz M. Managing asthma in adolescents and adults: 2020 asthma guideline update from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. JAMA. 2020;324(22):2301-2317. PMID: 33270095 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33270095/.

Del Giacco SR, Bakirtas A, Bel E, et al. Allergy in severe asthma. Allergy. 2017;72(2):207-220. PMID: 27775836 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27775836/.

Expert Panel Working Group of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) administered and coordinated National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Coordinating Committee (NAEPPCC), Cloutier MM, Baptist AP, Blake KV, et al. 2020focused updates to the asthma management guidelines: a report from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Coordinating Committee Expert Panel Working Group. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(6):1217-1270. PMID: 33280709 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33280709/.

Farne HA, Wilson A, Powell C, Bax L, Milan SJ. Anti-IL5 therapies for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9:CD010834. PMID: 28933516 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28933516/.

Fuchs O, Bahmer T, Rabe KF, von Mutius E. Asthma transition from childhood into adulthood. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(3):224-234. PMID: 27666650 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27666650/.

Israel E, Reddel HK. Severe and difficult-to-treat asthma in adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(10):965-976. PMID: 28877019 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28877019/.

Jolliffe DA, Greenberg L, Hooper RL, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent asthma exacerbations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(11):881-890. PMID: 28986128 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28986128/.

Lemière C, Vandenplas O. Asthma in the workplace. In: Broaddus VC, Mason RJ, Ernst JD, et al, eds. Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016:chap 72.

Lugogo N, Que LG, Gilstrap DL, Kraft M. Asthma: clinical diagnosis and management. In: Broaddus VC, Mason RJ, Ernst JD, et al, eds. Murray and Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016:chap 42.

Mauer Y, Taliercio RM. Managing adult asthma: The 2019 GINA guidelines. Cleve Clin J Med. 2020;87(9):569-575. PMID: 32868307 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32868307/.

McCracken JL, Veeranki SP, Ameredes BT, Calhoun WJ. Diagnosis and management of asthma in adults: a review. JAMA. 2017;318(3):279-290. PMID: 28719697 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28719697/.

Nasim F, Iyer VN. Bronchial thermoplasty-an update. Ann Thorac Med. 2018;13(4):205-211. PMID: 30416591 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30416591/.

Parsons JP, Hallstrand TS, Mastronarde JG, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline:exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(9):1016-1027. PMID: 23634861 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23634861/.

Smith LJ, Kalhan R, Wise RA, et al; American Lung Association Asthma Clinical Research Centers. Effect of a soy isoflavone supplement on lung function and clinical outcomes in patients with poorly controlled asthma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(20):2033-2043. PMID: 26010632 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26010632/.

Sobieraj DM, Weeda ER, Nguyen E, et al. Association of inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting ß-agonists as controller and quick relief therapy with exacerbations and symptom control in persistent asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;319(14):1485-1496. PMID: 29554195 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29554195/.

Sobieraj DM1, Baker WL1, Nguyen E, et al. Association of inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting muscarinic antagonists with asthma control in patients with uncontrolled, persistent asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;319(14):1473-1484. PMID: 29554174 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29554174/.

van de Griendt EJ, Tuut MK, de Groot H, Brand PLP. Applicability of evidence from previous systematic reviews on immunotherapy in current practice of childhood asthma treatment: a GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e016326. PMID: 29288175 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29288175/.

Viswanathan RK, Busse WW. Management of asthma in adolescents and adults. In: Burks AW, Holgate ST, O'Hehir RE, et al, eds. Middleton's Allergy: Principles and Practice. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 52.von Mutius E, Smits HH. Primary prevention of asthma: from risk and protective factors to targeted strategies for prevention. Lancet. 2020;396(10254):854-866. PMID: 32910907 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32910907/.

Wechsler ME, Yawn BP, Fuhlbrigge AL, et al; BELT Investigators. Anticholinergic vs long-acting ß-agonist in combination with inhaled corticosteroids in black adults with asthma: the BELT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(16):1720-1730. PMID: 26505596 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26505596/.

Woodruff PG, Bhakta NR, Fahny JV. Asthma: pathogenesis and phenotypes. In: Broaddus VC, Mason RJ, Ernst JD, et al, eds. Murray and Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016:chap 41.

-

Asthma - description

Animation

-

Your lungs: The inflammatory response

Animation

-

The inflammatory response: Symptoms and causes of airflow limitation

Animation

-

Asthma symptoms, triggers, and management

Animation

-

Asthma - description

Animation

-

Your lungs: The inflammatory response

Animation

-

The inflammatory response: Symptoms and causes of airflow limitation

Animation

-

Asthma symptoms, triggers, and management

Animation

Related Information

ecReview Date: 5/31/2021

Reviewed By: Stuart I. Henochowicz, MD, FACP, Clinical Professor of Medicine, Division of Allergy, Immunology, and Rheumatology, Georgetown University Medical School, Washington, DC. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.