Exercise - InDepth

Fitness recommendations - InDepth; Exercise - physical activity - InDepthAn in-depth report about the benefits and types of exercise.

Highlights

Overview

- Exercise is important for physical health and mood.

- The American Heart Association recommends that individuals do moderate exercise for at least 150 minutes per week, or vigorous exercise for 75 minutes per week. This is in addition to moderate to high-intensity muscle strengthening exercises 2 days a week.

- No one is too young or too old to exercise.

- Find an activity you enjoy, vary your activity daily, or join a group exercise program. Group exercise can take place in a number of settings including community (local centers and churches), hospital, and workplace.

Benefits of Exercising

- Exercise is associated with lower all-cause mortality in healthy individuals, as well as in those with long-term (chronic) diseases, diabetes, and older adults. People who engage in physical activity of around 150 minutes per week have 33% lower risk of all-cause mortality than physically inactive people.

- Exercise helps the heart, both by improving exercise capacity and by reducing the risk of heart disease and premature death. In addition, people with heart disease can gain important benefits from exercising, though they need medical clearance and may need special precautions.

- A recent review of available studies has shown that exercise benefits patients at all stages of dementia, improving balance, mobility, and the ability to perform basic activities of daily living.

- Aerobic exercise and resistance training, alone or in combination, improves blood sugar control in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Tips for Exercising

- Drink plenty of fluids before, during, and after a workout.

- Warming up and cooling down are important parts of every exercise routine. They help the body make the transition from rest to activity and back again, and can help prevent soreness or injury, such as in older people.

- Wear clothing that wicks moisture away from the body if you expect to sweat a lot.

- Be aware of temperature, humidity, and air quality when exercising indoors or outside. Exercising in very hot or cold temperatures can pose a hazard if you are not prepared.

- When exercising, listen to your body for warning symptoms, such as pain, numbness, or trouble breathing.

Motivation

- Develop an interest or hobby that requires physical activity.

- Adopt simple routines such as climbing the stairs instead of taking the elevator, walking instead of driving to the local newsstand, or canoeing instead of zooming along in a powerboat.

- Try cross-training (alternating between several types of exercises).

- Exercise with friends. Walking in groups can be an effective way to increase physical activity.

Introduction

To enjoy a long and healthy life, everyone should make wise lifestyle choices that include eating a healthy diet, exercising regularly, and maintaining normal weight. The combination of inactivity and eating the wrong foods is the second most common preventable cause of death in the United States (smoking is the first).

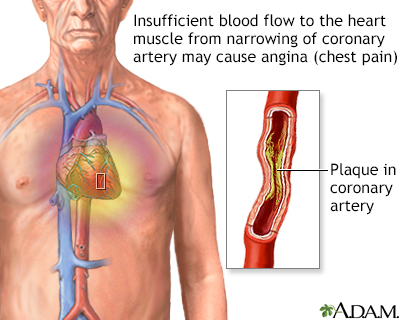

Most research on the benefits of exercise focuses on heart protection. Studies clearly show that exercise helps the heart. In addition, studies are reporting that even people with heart disease may gain important benefits from exercising, though they need medical clearance and may need special precautions.

Evidence suggests that our genes evolved to favor exercise. In other words, during prehistoric times, if a person couldn't move quickly and was not strong, that person died. Those who were fit survived to reproduce and pass on their "fitter" genes. Some researchers believe that with our current inactive lifestyle, these genes produce a number of bad effects, which can lead to many long-term (chronic) illnesses.

The benefits of exercise include:

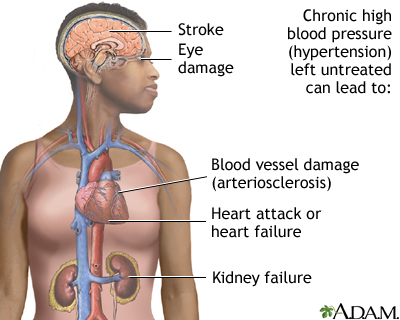

- Decreased risk of cardiovascular (heart) disease, high blood pressure, and stroke

- Decreased risk of colon and breast cancers

- Decreased risk of type 2 diabetes

- Decreased risk of osteoporosis

- Decreased risk of depression and dementia

- Decreased body fat

- Improved metabolic processes (the way the body breaks down and builds necessary substances)

- Improved movement of joints and muscles

- Improved oxygen delivery throughout the body

- Improved sense of well-being

- Improved strength and endurance

- Reduced inflammation

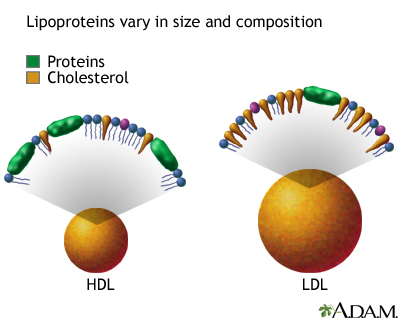

- Increased HDL (good) cholesterol

In addition, exercise can help change other dangerous lifestyle habits. Exercise increases the likelihood of not smoking and appears to decrease nicotine withdrawal and smoking cravings. Other studies seem to indicate that starting exercise training motivates people to choose healthier diets.

No one is too young or too old to exercise. The American Heart Association recommends that individuals do moderate exercise, such as brisk walking, for at least 150 minutes per week (such as 30 minutes per day for 5 days a week), or vigorous exercise for 75 minutes per week. However, vigorous exercise carries risks that people should discuss with a health care provider. You should always check with your provider before starting a new exercise program, especially if you have any of the following risk factors:

- A symptom you have never told your provider about

- Arthritis of the hips or knees

- Blood clots

- Chest pain

- Long-term (chronic) lung disease

- Diabetes

- Eye injury or recent eye surgery

- Family history of a cardiovascular disease

- Foot or ankle sores that will not heal

- Heart disease

- Heart palpitations

- Hernia

- High blood pressure

- History of smoking

- Infections

- Joint swelling

- Obesity

- Pain or trouble walking after a fall

- Shortness of breath

About 50% of all people who begin a vigorous training program drop out within a year. The key to reaching and maintaining physical fitness is to find activities that are exciting, challenging, and satisfying.

Recommended Exercise Methods

A few simple rules are helpful as you develop your own routine.

- Do not eat for 2 hours before vigorous exercise.

- Drink plenty of fluids before, during, and after a workout.

- Adjust your activity level according to the weather and reduce it when you are fatigued or ill.

When exercising, listen to the body's warning symptoms, and consult a provider if exercise causes chest pain, irregular heartbeat, unusual fatigue, nausea, unexpected breathlessness, or lightheadedness.

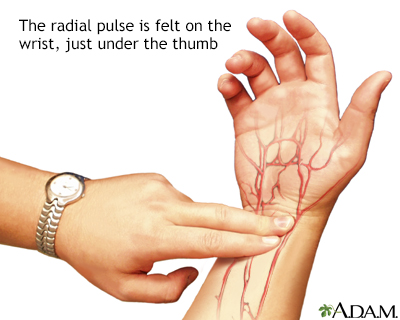

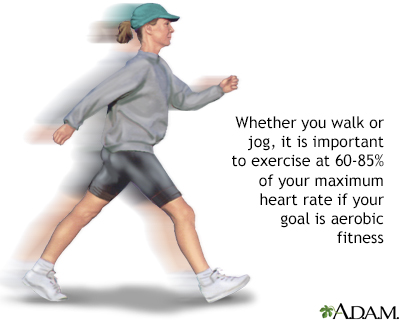

Heart Rate Goal

Heart rate is the standard guide for determining aerobic exercise intensity. It is useful for people training at aerobic intensity, or people with certain cardiac risk factors who have been set a maximum heart rate by their provider. You can determine your heart rate by counting your pulse, or by using a heart rate monitor, such as a wearable fitness band or activity watch. To feel your own pulse, press the first two fingers of one hand gently down on the inside of the wrist or under the jaw on the right or left side of the front of the neck. You should feel a faint pounding as blood passes through the artery. Each pounding is a beat.

Heart rate terms that are important for exercise are:

Resting Heart RateThe average heart rate for an adult at rest is 60 to 80 beats per minute. It is usually lower for people who are physically fit, and often rises as you get older. You can determine your resting heart rate by counting how many times your heart beats in 1 minute in resting conditions. The best time to do this is in the morning after a good night's sleep before you get out of bed.

Maximum Heart RateTo determine your own maximum heart rate per minute subtract your age from 220. For example, if you are 45, you would calculate your maximum heart rate as follows: 220 - 45 = 175.

Target Heart RateYour initial target rate is 50% to 75% of your maximum heart rate. You should measure your pulse off and on while you exercise to make sure you stay within this range. After about 6 months of regular exercise, you may be able to increase your target heart rate to 85% (but only if you can comfortably do so).

Certain heart medications may lower your maximum and target heart rates. Always check with your provider before starting an exercise program.

Note: Swimmers should use a heart rate target of 75% of the maximum and then subtract 12 beats per minute. The reason for this is that swimming will not raise the heart rate quite as much as other sports because of the so-called "diving reflex," which causes the heart to slow down automatically when the body is immersed in water.Target Heart Rates for a One-minute Pulse Count | ||

Age | Low | High |

(50% max) | (75% max) | |

20 | 100 | 150 |

30 | 95 | 142 |

40 | 90 | 135 |

50 | 85 | 127 |

60 | 80 | 120 |

Source: American Heart Association | ||

- After running at top pace for 15 minutes, round off the distance run to the nearest 25 meters.

- Divide that number by 15.

- Subtract 133.

- Multiply the total by 0.172, and then add 33.3.

Olympic and professional endurance athletes train for VO2 max levels above 80. Non-athletes VO2 max levels vary according to sex and age and range from 30 to 50 for males and 20 to 40 for females. For the average person exercising for fitness and health, calculating or using this value is not necessary.

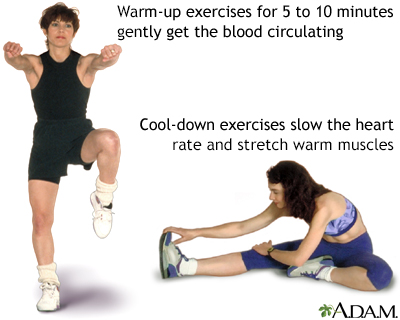

Warm-Up and Cool-Down

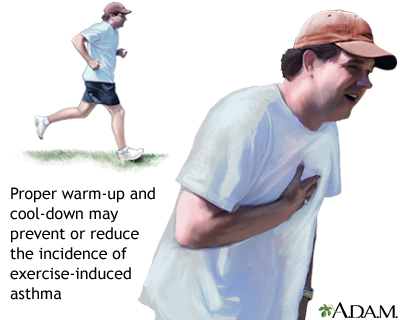

Warming up and cooling down are important parts of every exercise routine. They help the body make the transition from rest to activity and back again, and may help prevent soreness or injury, such as in older people.

- Perform warm-up exercises for 5 to 10 minutes at the beginning of an exercise session. Older people need a longer period to warm up their muscles. Stretching exercises, gentle calisthenics, and walking are ideal.

- To cool down, you should walk slowly until the heart rate is 10 to 15 beats above your resting heart rate. Stopping too suddenly can sharply reduce blood pressure, and is dangerous for older people. It may also cause muscle cramping.

- Stretching may be appropriate for the cooling down period, but it must be done carefully for warming up because it can injure cold muscles.

By properly warming up the muscles and joints with low-level aerobic movement for 5 to 10 minutes, one may help avoid injury. Cooling down after exercise by walking slowly, then stretching muscles, may also prevent strains and blood pressure fluctuation.

For most people, exercise may be divided into three general categories:

- Aerobic or endurance

- Strength or resistance

- Flexibility

A balanced program should include all three. Speed training is also a major category, but generally only competitive athletes practice it.

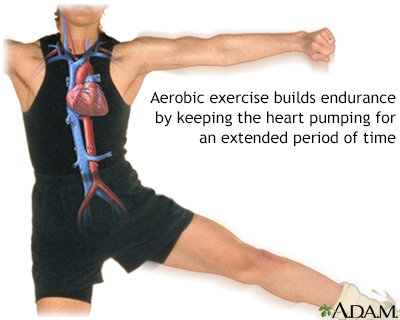

Aerobic (Endurance) Training

Benefits of Aerobic ExerciseRegular aerobic exercise provides the following benefits:

- Protection from heart attack, stroke, type 2 diabetes, dementia, depression, colon and breast cancers, and early death

- Builds endurance

- Keeps the heart pumping at a steady and high rate for a long time

- Boosts HDL (good) cholesterol levels

- Helps control blood pressure

- Strengthens the bones

- Helps maintain normal weight

- Improves one's sense of well-being

Aerobic exercise is usually categorized as high or low intensity. High-intensity aerobic exercise is further classified as high or low impact. Examples of each include the following:

- Low- to moderate-impact exercises: Examples include walking, swimming, biking, stair climbing, step classes, rowing, skating, and cross-country skiing. Nearly anyone in reasonable health can engage in some low- to moderate-impact exercise. Brisk walking burns almost as many calories as running for the same distance and poses less risk for injury to muscle and bone.

- High-impact exercises: Examples include running, dance exercise, tennis, racquetball, squash, soccer, and basketball. High impact exercises are excellent for cardiovascular conditioning, but they increase the risk of complications and are generally not suitable for people who are overweight, older, out of condition, or have an injury, arthritis, or other medical problem.

Aerobic Regimens

As little as 1 hour a week of aerobic exercises is helpful, but 3 to 4 hours per week are best. Some research indicates that simply walking briskly for 3 or more hours a week reduces the risk for coronary heart disease by 45%. In general, the following guidelines are useful for most individuals:

- For most healthy young adults, the best approach is a mix of low- and higher-impact exercise. Two weekly workouts will maintain fitness, but 3 to 5 sessions a week are better.

- People who are out of shape or older should start aerobic training gradually. For example, they may start with 5 to 10 minutes of low-impact aerobic activity every other day and build toward a goal of 30 minutes per day, 3 to 7 times a week. (For heart protection, weekly total is the key.)

- Swimming is an ideal exercise for many older people, and for certain people with physical limitations. People with physical limitations include pregnant women, individuals with muscle, joint, or bone problems, and those who suffer from exercise-induced asthma (EIA).

- People who seek to lose weight should concentrate on calories burnt each week, not the number of workout sessions.

One way of gauging the aerobic intensity of exercise is to aim for a "talking pace," which is enough to work up a sweat and still be able to converse with a friend without gasping for breath. As fitness increases, the "talking pace" will become faster and faster.

ShoesChoose a good pair of athletic shoes that are made well and fit well. They should support the ankle and provide cushioning for walking as well as for impact sports such as running or aerobic dancing. See the chart below.

Airing out the shoes and feet after exercising reduces chances for skin conditions such as athlete's foot. You can also purchase socks made with quick-drying fabrics that absorb sweat.

ClothingComfort and safety are the key words for workout clothing. For outdoor nighttime exercise, a reflective vest and light-colored clothing must be worn. Bikers, inline skaters, and equestrians should always wear safety devices such as helmets, wrist guards, and knee and elbow pads. Goggles are mandatory for indoor racquet sports. For vigorous athletic activities, such as football, ankle braces may be more effective than tape in preventing ankle injuries.

If you are going to sweat, or workout in warm conditions, choose fabrics that pull sweat away from your skin and dry quickly. Many quick-drying fabrics are synthetic, made of polyester or polypropylene. Look for terms like moisture-wicking, Dri-FIT, CoolMax, or Supplex. Wool is also a good choice to keep you cool, dry, and naturally odor free. Some workout clothing is made with special antimicrobial solutions to combat odor from sweat.

Cotton clothing is OK for light activities, but it is not the best choice. Cotton absorbs sweat and does not dry quickly. Because it stays wet, it can make you cold, which can be dangerous in cold weather. In warm weather, it is not as good as synthetic fabrics at keeping you cool and dry if you sweat a lot.

Avoid working out in fabrics that do not breathe, like Gore-Tex, plastics, or rubber-based materials.

In general, make sure your clothing does not get in the way of your activity. You want to be able to move easily. Clothing should not catch on equipment or slow you down.

You can wear loose-fitting clothing for activities like:

- Walking

- Gentle yoga

- Strength training

- Basketball

You may want to wear form-fitted, stretchy clothing for activities like:

- Running

- Biking

- Advanced yoga/Pilates

- Swimming

You may be able to wear a combination of loose and form-fitting clothing. For example, you might wear a moisture-wicking loose t-shirt, with fitted shorts.

Aerobic Exercise Indoor EquipmentHome aerobic exercise machines can be adapted to any fitness level and used day or night. Before investing in any exercise machine, however, it is wise to first test it at a gym. In addition, initial supervised training when using these machines can reduce the risk of injury that might occur with self-instruction.

Very inexpensive exercise machines tend to be flimsy and hard to adjust, but many sturdy machines are available at moderate prices. The higher-end models may utilize computers to record calories burned, speed, and mileage. Their readouts may provide motivation and gauge the intensity of a workout; however, they are not always accurate.

The following are a few observations on specific equipment:

- A good floor mat is important to provide cushioning for all home exercises.

- A simple jump rope improves aerobic endurance for people who are able to perform high-impact exercise. Jumping rope should be done on a floor mat plus a surface that has some give to avoid joint injury.

- For burning calories, the treadmill has been ranked best, followed by stair climbers, the rowing machine, cross-country ski machine, and stationary bicycle. (Elliptical trainers, however, may be even better than treadmills for increasing heart rate, calorie expenditure, and oxygen consumption.)

- Stationary bikes condition leg muscles and are fairly economical and easy to use safely. The pedals should turn smoothly, the seat height should adjust easily, and the bike's computer should be able to adjust intensity.

- Stair machines also condition leg muscles. They offer very intense, low-impact workouts and may be as effective as running with less chance of injury.

Rowing and cross-country ski machines exercise both the upper and lower body.

Shoes for Sports | ||

| Aerobic dancing | Sufficient cushioning to absorb shock and pressure that are many times greater than ordinary walking. Arches that maintain side-to-side stability. Thick upper leather support. Toe-box. Orthotics may be required for people with ankles that over-turn inward or outward. Soles should allow for twisting and turning. | |

| Cycling | Rigid support across the arch to distribute pressure during pedaling. Heel lift. Cross-training or combination hiking/cycling shoes may be sufficient for casual bikers. Toe clips or specially designed shoe cleats for serious cyclers. In some cases, orthotics may be needed to control arch and heel and balance forefoot. | |

| Running | Sufficient cushioning to absorb shock and pressure. Flexible at the ball of the foot. Sufficient traction on sole to prevent slipping. Consider insoles or orthotics with arch support for problem feet. | |

| Tennis | Low-traction soles. Snug-fitting heels with cushioning. Padded toe box with adequate depth. Soft-support arch. | |

| Walking | Lightweight. Breathable upper material (leather or mesh). Wide enough to accommodate ball of the foot. Firm padded heel counter that does not bite into heel or touch ankle bone. Low heel close to ground for stability. Good arch support. Front provides support and flexibility. | |

Sports such as basketball, football, soccer | Choose sport-specific sneakers or cleats that match the activity. | |

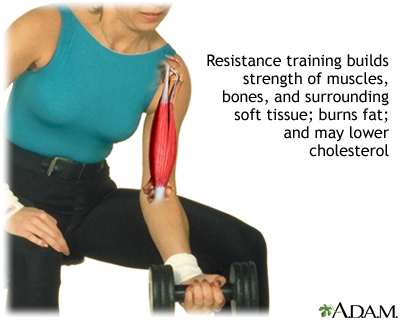

Strength or Resistance Training

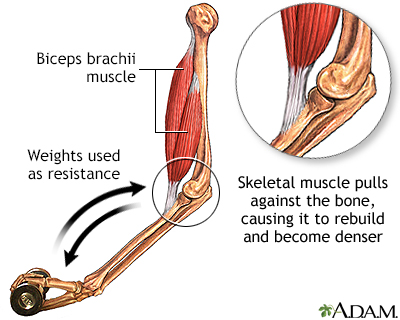

Benefits of Strength ExerciseWhile aerobic exercise increases endurance and helps the heart, it does not build upper body strength or tone muscles. Strength-training exercises provide the following benefits:

- Build muscle strength while burning fat

- Help maintain bone density

Strength training exercises are also associated with a lower risk for heart disease, possibly because it lowers LDL (the so-called "bad" cholesterol) levels.

Strength exercise is beneficial for everyone, independent of age. It is the only form of exercise that can slow and even reverse the decline in muscle mass, bone density, and strength that occur with aging.

Note: People at risk for cardiovascular disease should not perform strength exercises without checking with a provider.Types of Muscle ContractionsThere are three types of muscle contractions involved in strength training:

- Isometric contractions do not change the length of the muscle. An example is pushing against a wall.

- Concentric contractions shorten muscles. An example is the "up" phase of the biceps curl.

- Eccentric contractions lengthen muscles. An example is the "down" phase as weights are lowered.

Strength Training Regimens

Strength training involves intense and short-duration activities. For beginners, adding 10 to 20 minutes of modest strength training 2 to 3 times a week may be appropriate. The following are some guidelines for starting a strength regimen:

- The sequence of a strength training session should begin with training large muscles and multiple joints at higher intensity, and end with small muscle and single joint exercises at lower intensities.

- You should perform both shortening and lengthening muscle actions. Emphasizing the movements that lengthen muscles is of increasing interest. This approach involves slowing and increasing the duration of these "down" movements. It appears to significantly increase blood flow, and some evidence suggests it may achieve stronger muscles more quickly. It may also improve heart function compared to standard movements. Exercises that lengthen muscles may be particularly beneficial for older people and some people with long-term (chronic) health problems. This type of training increases the risk for muscle soreness and injury, however, and this approach is still controversial.

- Strength training involves moving specific muscles in the same pattern against a resisting force (such as a weight) for a preset number of times. This is called a repetition. People should first choose a weight that is about half of what would require a maximum effort in one repetition. In other words, if it would take maximum effort to do a single repetition with a 10-pound (4.5 kilogram) dumbbell, the person would start with a 5-pound (2.3 kilogram) dumbbell. In the beginning, most people can start with one set of 8 to 15 repetitions per muscle group with low weights. As individuals are able to perform 1 or 2 repetitions over their routine, weights can be increased by 2% to 10%.

- Breathe slowly and rhythmically. Exhale as the movement begins. Inhale when returning to the starting point.

- The first half of each repetition typically lasts 2 to 3 seconds. The return to the original position lasts 4 seconds.

- Joints should be moved rhythmically through their full range of motion during a repetition. Do not lock up the joint while exercising it.

- For maximum benefit, allow 48 hours between workouts for full muscle recovery.

Unlike aerobic exercise, strength training almost always requires some equipment. Strength-training equipment does not, however, have to cost anything.

- Any heavy object that can be held in the hand, such as a plastic bottle filled with sand or water, can serve as a weight.

- Dumbbells (1 to 10 pounds [0.45 to 4.5 kilograms]) and resistance bands are inexpensive, portable, and effective.

- Wearable wrist weights help strengthen and tone the upper body.

- Ankle weights strengthen and tone muscles in the lower body. They should not be worn during high-impact aerobics or jumping.

- Hand grips strengthen arms and are good for relieving tension.

- A pull-up bar can be mounted in a doorway for chin-ups and pull-ups.

More elaborate and expensive home equipment for working body muscles is also available. No one should purchase or use strength-training equipment without instruction from a professional.

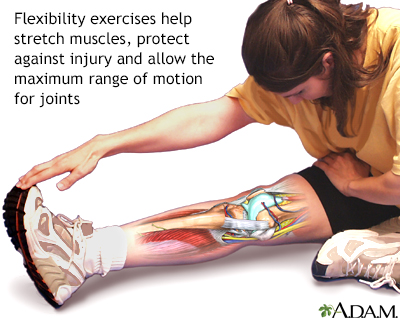

Flexibility Training (Stretching)

Benefits of Flexibility TrainingFlexibility training uses stretching exercises. Many stretching exercises are particularly beneficial for the back. In general, flexibility training provides the following benefits:

- Prevents cramps, stiffness, and injuries

- Improves joint and muscle movement (improved range of motion)

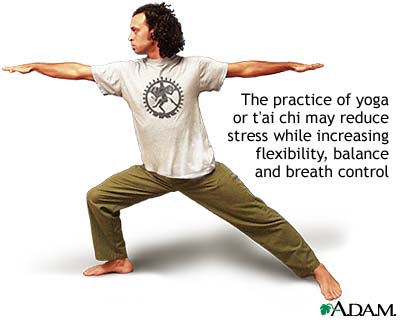

Certain flexibility practices, such as yoga and Tai chi, also involve meditation and breathing techniques that reduce stress. Such practices appear to have many health and mental benefits. They may be very suitable and highly beneficial for older people, and for people with certain long-term (chronic) diseases.

Flexibility Training Regiments

Providers recommend performing stretching exercises for 10 to 12 minutes at least 3 times a week. The following are some general guidelines:

- When stretching, exhale and extend the muscles to the point of tension, not pain, and hold for 20 to 60 seconds. (Beginners may need to start with a 5- to 10-second stretch.)

- Breathe evenly and constantly while holding the stretch.

- Inhale when returning to a relaxed position. Holding your breath defeats the purpose; it causes muscle contraction and raises blood pressure.

- When doing stretches that involve the back, relax the spine to keep the lower back flush with the mat, and to work only the muscles required for changing position (often these are only the abdominal muscles).

Specific Exercise Tips for Older People

Studies continue to show that it is never too late to start exercising. Older adults who exercise twice a week can significantly increase their body strength, flexibility, balance, and agility. Even small improvements in physical fitness and activity can prolong life and independent living, even for those who increase their physical activity after the age of 50 years.

Still, according to the 2010 Healthy People report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 46% of people ages 65 to 74 years did not engage in any leisure time physical activity in 2008, the last year for which figures were available. In people over age 75 years, the percentage of those not engaged in any leisure time physical activity was 56%.

The following tips for exercising may be helpful:

- Any older person should have a complete physical and medical examination, as well as professional instruction, before starting an exercise program.

- Start low and go slow. For sedentary, older people, one or more of the following programs may be helpful and safe: Low-impact aerobics, gait (step) training, balance exercises, Tai chi, self-paced walking, and lower legs resistance training, using elastic tubing or ankle weights. Even in the nursing home, programs aimed at improving strength, balance, gait, and flexibility have significant benefits.

- Strength training assumes even more importance as one ages, because after the age of 30 years everyone undergoes a slow process of muscular weakening (atrophy). This process can be reduced or even reversed by adding resistance training to an exercise program. As little as 1 day a week of resistance training improves overall strength and agility. Strength training also improves heart and blood vessel health.

- Flexibility exercises promote healthy muscles and help reduce the stiffness and loss of balance that accompanies aging.

- Chair exercises may be performed by people who are unable to walk.

- Older women are at risk for incontinence accidents during exercise. This can be reduced or prevented by performing Kegel exercises, limiting fluids (without risking dehydration), going to the bathroom frequently, and using leakage prevention pads or insertable devices.

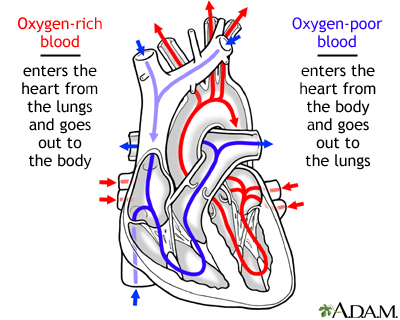

How Exercise Affects the Heart

Inactivity is one of the major risk factors for heart disease. Exercise helps improve heart health, and can even reverse some heart disease risk factors.

Like all muscles, the heart becomes stronger as a result of exercise, so it can pump more blood through the body with every beat and continue working at maximum level, if needed, with less strain. The resting heart rate of those who exercise is also slower because less effort is needed to pump blood.

A person who exercises often and vigorously has the lowest risk for heart disease, but any amount of exercise is beneficial. Studies consistently find that light-to-moderate exercise is even beneficial in people with existing heart disease. Note, however, that anyone with heart disease or cardiac risk factors should seek medical advice before beginning a workout program.

The heart is a large muscular organ that pumps blood throughout the body. Valves inside the heart open and close. This controls how much blood enters or leaves the heart.

Effects of Exercise on Heart Disease and Cholesterol

Exercise has a number of effects that benefit the heart and circulation (blood flow throughout the body). These benefits include improving cholesterol and fat levels, reducing inflammation in the arteries, helping weight loss programs, and helping to keep blood vessels flexible and open. Studies continue to show that physical activity and avoiding high-fat foods are the two most successful means of reaching and maintaining heart-healthy levels of fitness and weight.

The American Heart Association recommends that individuals perform moderate exercise for at least 150 minutes per week, or 75 minutes per week of vigorous exercise. Muscle-strengthening activities at least 2 days a week are also recommended. This recommendation supports similar exercise guidelines issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Coronary Artery DiseasePeople who maintain an active lifestyle have a 45% lower risk of developing heart disease than do sedentary people. Experts have been attempting to define how much exercise is needed to produce heart benefits. Beneficial changes in cholesterol and lipid levels, including lower LDL (bad cholesterol) levels, occur even when people performed low amounts of moderate- or high-intensity exercise, such as walking or running 12 miles a week. Benefits occur even with very modest weight loss, suggesting that overweight people who have trouble losing pounds can still achieve considerable heart benefits by exercising.

Some studies suggest that for the greatest heart protection, it is not the duration of a single exercise session that counts but the total weekly amount of energy expended.

Resistance (weight) training has also been associated with heart protection. It may offer a complementary benefit to aerobics. If you have heart disease or risk factors for heart disease, check with your provider before starting resistance training.

Effects of Exercise on Blood PressureRegular exercise helps keep arteries elastic (flexible), even in older people. This, in turn, ensures good blood flow and normal blood pressure. Sedentary people have a 35% greater risk of developing high blood pressure than physically active people do.

For lowering blood pressure, the American Heart Association recommends an average of 40 minutes of moderate to vigorous aerobic activity 3 to 4 times per week. Experts recommend at least 30 minutes of exercise on most -- if not all -- days. Studies show that yoga and Tai chi, an ancient Chinese exercise involving slow, relaxing movements, may lower blood pressure almost as well as moderate-intensity aerobic exercises.

Anyone with existing high blood pressure should discuss an exercise program with their provider. Before starting to exercise, people with moderate-to-severe high blood pressure should lower their blood pressure, and be able to control it with medications. Everyone, especially people with high blood pressure, should breathe as normally as possible through each exercise. Holding your breath during strength exercises increases blood pressure.

Effects of Exercise on Heart FailureTraditionally, heart failure patients have been discouraged from exercising. Now, exercise performed under medical supervision is proving to be helpful for select patients with stable heart failure.

Progressive resistance training may be particularly useful for heart failure patients, since it strengthens muscles, which commonly weaken in this disorder. Simply performing daily handgrip exercises can improve blood flow through the arteries.

Experts warn, however, that exercise is not appropriate for all heart failure patients.

Effects of Exercise on Stroke

Physical activity lowers stroke risk.

All stroke survivors should have a medical evaluation before starting an exercise program.

The effects of exercise on stroke are less established than those on heart disease, but most studies show benefits.

Exercise Programs for High-Risk Individuals

Anyone with heart disease or risk factors for developing heart disease or stroke should seek medical advice before beginning a workout program. People with heart disease can nearly always exercise safely as long as they are evaluated beforehand and advised on effort limits. Some will need to begin their workout under medical supervision. Still, it is often difficult for a provider to predict health problems that might arise as the result of an exercise program. At-risk individuals should be very aware of any symptoms warning of harmful complications while they exercise.

Some believe that anyone over 40 years old, whether or not they are at risk for heart disease, should have a complete physical examination before starting or intensifying an exercise program. Some providers use a questionnaire for people over 40 to help determine whether they need an examination. The questions they use often include:

- Has any provider previously recommended medically supervised activity because of a heart condition?

- Does physical activity bring on chest pain?

- Has chest pain occurred during the previous month?

- Does the person faint or fall over from dizziness?

- Does bone or joint pain intensify during or after exercise?

- Has medication been prescribed for hypertension (high blood pressure) or heart problems?

- Is the person aware of, or has a provider suggested, any physical reason for not exercising without medical supervision?

Those who answer "yes" to any of the above questions should have a complete medical examination before developing an exercise program.

Some people should get a cardiac evaluation and a stress test.

Stress TestA stress test helps determine the risk for a heart problem resulting from exercise. Anyone with a heart condition or history of heart disease should ask their health care provider about whether to have a stress test before starting an exercise program. Some health care professionals also recommend this test before a vigorous exercise program for older people who are sedentary, even in the absence of known or suspected heart disease. The test is expensive, however. Many providers believe that it is not necessary for older people who start low to moderate intensity exercise such as walking and have no evident health problems or risk factors.

Heart Attack and Sudden Death from Strenuous Exercise

A small percentage of heart attacks occur after heavy physical work.

High-Risk IndividualsIn general, the following people should avoid intense exercise or start it only gradually with careful medical supervision:

- People who have diabetes, uncontrolled seizures, uncontrolled high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, heart failure, unstable angina, significant aortic valve disease, or aortic aneurysm should check with their provider before starting an exercise program.

- People with moderate-to-severe hypertension: Moderate or severe high blood pressure (systolic blood pressure over 160 mm Hg or diastolic (lower number) pressure over 100 mm Hg) should be brought to lower levels before a person starts a vigorous exercise program.

- Sedentary people should be cautious and build the intensity of their exercise up slowly.

People should keep the risk for heart attack from exercise in perspective, however. Some form of exercise, carefully personalized, has benefits for most of the individuals mentioned above. In many cases, particularly when the only risk factors are a sedentary lifestyle and older age, exercise can often be increased over time until it is intense.

Episodes of exercise-related sudden death in young people are rare but of great concern. Some are preceded by fainting, which is due to a sudden and severe drop in blood pressure. It should be noted that fainting is relatively common in athletes, but it should always result in a careful medical evaluation. Young people with genetic or congenital (present at birth) heart disorders should avoid intensive competitive sports.

High dose anabolic steroids and products containing ephedra have been associated with cases of stroke, heart attack, and even death. Energy drinks and supplements have also raised concern.

Hazardous Activities for High-Risk IndividualsThe following activities may pose particular dangers for high-risk individuals:

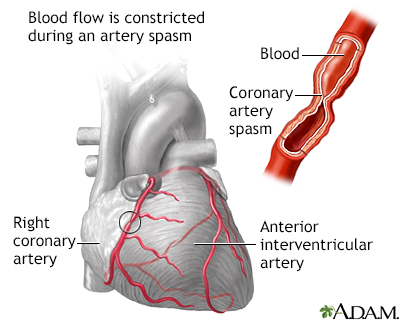

- Intense exercise may be hazardous for people with risk factors for heart disease, such as with older people, and in harsh weather conditions such as heat, humidity, or extreme cold. Snow shoveling heads the list; other examples include running, race walking, singles tennis, heavy lifting, heavy gardening. These workouts tend to stress the heart, raise blood pressure for a brief period, and may cause spasms in the arteries leading to the heart. (See image: Coronary Artery Spasm)

- Some studies suggest that competitive sports, which couple intense activity with aggressive emotions, are more likely to trigger a heart attack than other forms of exercise.

Young men who die suddenly during a workout may have previously experienced, and ignored, warning signs of heart disease. In addition to avoiding risky activities, the best preventive tactic is simply to listen to the body and seek medical help at the first sign of symptoms during or following exercise. These symptoms include:

- Irregular heartbeat

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain

- Lightheadedness or dizziness

- Fainting

How Exercise Affects Diabetes

Moderate aerobic exercise can lower your risk for type 2 diabetes.

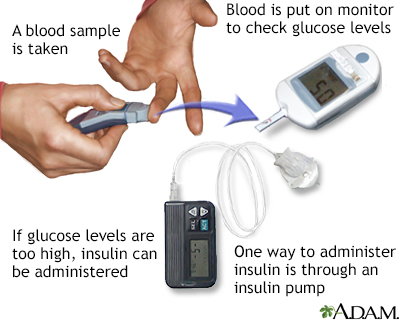

Exercise has positive benefits for those who have diabetes. It can lower blood sugar levels, improve insulin sensitivity, and strengthen the heart. Strength training, which increases muscle and reduces fat, may be particularly helpful for people with diabetes. In a recent study of overweight adults, intensive lifestyle interventions (frequent individual and group diet and activity counseling) were shown to be more effective than three annual diabetes support and education (DSE) visits in improving type 2 diabetes remission rates.

People with diabetes who begin a new or vigorous exercise program should have their eyes examined, and discuss footwear and heart risks with their doctor.

Type 1 DiabetesAerobic exercise has significant and particular benefits for people with type 1 diabetes. It increases sensitivity to insulin, lowers blood pressure, improves cholesterol levels, and decreases body fat.

Type 2 DiabetesAerobic exercise and resistance training, alone or in combination, improves control of blood sugar levels in people with type 2 diabetes. Training of more than 150 minutes per week is associated with better control, but even shorter time periods improve control.

For improving blood sugar control, the American Diabetes Association recommends at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity physical activity (50% to 70% of maximum heart rate) or at least 90 minutes per week of vigorous aerobic exercise (more than 70% of maximum heart rate). Exercise at least 3 days a week, and do not go more than 2 consecutive days without physical activity.

Strength TrainingStrength training, which increases muscle and reduces fat, is also helpful for people with diabetes who are able to do this type of exercise. The American Diabetes Association recommends performing resistance exercise 3 times a week. Build up to 3 sets of 8 to 10 repetitions using weight that you cannot lift more than 8 to 10 times without developing fatigue. Be sure that your strength training targets all of the major muscle groups.

Some Precautions for People with Diabetes Who Exercise

The following are precautions for all people with diabetes, whether type 1 or 2:

- Because people with diabetes are at higher than average risk for heart disease, they should always check with their providers before starting a demanding exercise program. For people who have been sedentary, or have other medical problems, lower-intensity exercises are recommended, using programs they designed with their providers.

- Strenuous strength training or high-impact exercise is not recommended for people with uncontrolled diabetes. Such exercises can strain weakened blood vessels in the eyes of people with retinopathy (a common diabetic complication). High-impact exercise may also injure blood vessels in the feet.

Patients who are taking medications that lower blood glucose, particularly insulin, should take special precautions before starting a workout program.

- Wear good, protective footwear to help avoid injuries and wounds to the feet.

- Glucose levels swing dramatically during exercise. People with diabetes should monitor their levels carefully before, during, and after workouts.

- People should probably avoid exercise if glucose levels are above 300 mg/dL or under 100 mg/dL.

- To avoid hypoglycemia (low blood sugar), people with diabetes should inject insulin in sites away from the muscles they use the most during exercise.

- People with diabetes should drink plenty of fluids. Before exercising, they should avoid alcohol and certain medications, such as beta blockers, which increase the risk of hypoglycemia.

- Insulin-dependent athletes may need to decrease insulin doses, or take in more carbohydrates, prior to exercise.

A person with diabetes must regularly check their blood sugar (glucose) level.

How Exercise Affects the Bones and Muscles

Exercise is critical for strong muscles and bones. Muscle strength declines as people age, but studies report that when people exercise they are stronger and leaner than others in their age group.

Exercise may help kids lower their risk of long-term (chronic) pain in the future.

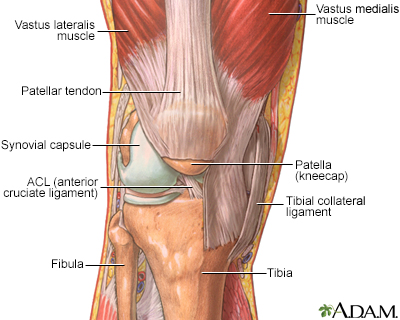

Joints are complex structures. They are designed to bear weight and move the body. Above the knee is the femur (thigh bone). Below the knee is the tibia (shin bone) and fibula. The kneecap is also called the patella. It rides on top of the lower portion of the femur and the top portion of the tibia. The muscles and ligaments connect these bones, and the space between them is cushioned by fluid-filled capsules (synovia) and cartilage. When you exercise, the muscles pull on the bones, strengthening them. The range of motion of a joint represents how far it can be flexed (bent) and extended (stretched).

Effects of Exercise on Osteoarthritis

Joints require motion to stay healthy. Long periods of inactivity cause the arthritic joint to stiffen and the adjoining tissue to weaken. A moderate exercise program that includes low-impact aerobics, flexibility exercises, and strength training has benefits for people with arthritis, even though it does not slow down the disease progression. Many people who start an exercise program report less disability and pain. They are also better able to perform daily chores, and they remain independent longer than their inactive peers. Older people and those with medical problems should always check with their provider before starting an exercise program.

The following are useful exercises for people with osteoarthritis:

- Strengthening exercises build muscle strength. Exercises to strengthen leg muscles are a reasonable first step, even before using pain relievers. Health care professionals fear that people who rely on painkilling drugs may overuse knees, which do not have strong enough muscle tissue to protect the joints from further damage. Strengthening the thigh muscles is certainly protective for those who have not developed osteoarthritis.

- Range-of-motion exercises increase the amount of movement in a joint and muscle. Examples are yoga and Tai chi, which focus on flexibility, balance, and proper breathing.

- Low-impact aerobic workouts help stabilize and support the joints. Cycling and walking are beneficial, and swimming or exercising in water is highly recommended for people with arthritis. People with arthritis should avoid high-impact sports, such as running, tennis, and racquetball.

- Some researchers are now focusing on "power" training, which involves improving the muscle's ability to move more rapidly against resisting forces, such as gravity. For example, such training helps people stand up or climb stairs more quickly. Muscle power declines more rapidly than muscle strength and may be particularly important in older people.

Exercises Effect on Fractures and Falls

Exercise is very important for slowing the progression of osteoporosis, and extremely important for reducing the risk of falling, which causes fractures. Falls are one of the leading causes of death in people over the age of 65 years. Exercise helps build balance and flexibility, which reduces the risk of falling.

Specific exercises may be helpful for reducing the risk of fractures:

- Weight-bearing exercise is very beneficial for bones in people of all ages, including older people. This approach applies tension to muscle and bone, and the body responds to this stress by increasing bone density, in young adults by as much as 2% to 8% a year. Careful weight training can also be very beneficial for older people, particularly women. In addition to improving bone density, weight-bearing exercise reduces the risk of fractures by improving muscle strength and balance, thus helping to prevent falls.

- Regular brisk long walks improve bone density and mobility. In one study, for example, older women reduced their risk of hip fracture by over 40% by working out just 4 hours a week.

- Exercises specifically targeted to strengthen the back can be beneficial in improving posture, and may even reduce kyphosis (hunchback) in people with osteoporosis.

- Low-impact exercises, particularly yoga and Tai chi, which improve balance and strength, have been found to decrease the risk of falling. In one study, Tai chi reduced this risk by almost half.

Note on Female Athlete Triad

Some young female athletes who exercise very intensely, and are subject to intense pressure to remain thin, are at risk for the female athlete triad. This syndrome is a combination of three disorders -- an eating disorder, loss of menstrual periods, and osteoporosis.

Effect of Exercise on Back Pain

People who do not exercise regularly face an increased risk for low back pain, such as during times when they suddenly have to perform stressful, unfamiliar activities. These activities may include shoveling, digging, or moving heavy items. Although no definitive studies have been done to prove the relationship between lack of exercise and low back pain, sedentary living is probably a contributing risk factor for this condition.

Lack of exercise leads to the following conditions that may threaten the back:

- Muscle inflexibility can restrict the back's ability to move, rotate, and bend.

- Weak stomach muscles can increase the strain on the back and can cause an abnormal tilt of the pelvis (hip bones).

- Weak back muscles may increase the load on the spine and the risk of disk compression.

- Obesity puts more weight on the spine and increases pressure on the vertebrae and disks. However, studies report only a weak association between obesity and low back pain.

People with sudden and severe back pain should not exercise. However, exercise plays a very beneficial role in relieving long-term (chronic) back pain.

Exercise should be considered as part of a broader program to return to normal home, work, and social activities. In this way, the positive benefits of exercise not only affect strength and flexibility but they also alter and improve the person's attitudes toward their disability and pain.

Repetition is the key to increasing flexibility, building endurance, and strengthening the specific muscles needed to support the spine. Some exercise programs used for prevention or treatment of long-term (chronic) low back pain include:

- Low-impact aerobic exercises: Low-impact aerobic exercises, such as swimming, bicycling, and walking, can strengthen muscles in the abdomen and back without over-straining the back. Programs that use strengthening exercises while swimming may be a particularly beneficial approach for many people with back pain.

- Lumbar extension strength training: Exercises called lumbar extension strength training are proving to be effective. Generally, these exercises attempt to strengthen the abdomen, and improve lower back mobility, strength, and endurance. They also enhance flexibility in the hip and hamstring muscles, and in the tendons at the back of the thigh.

- Yoga, Tai chi, and Chi kung: These exercises combine low-impact physical movements and meditation. They are based on principles of disciplining the mind to achieve a physical and mental balance. They can be very helpful in preventing recurrences of low back pain. This approach deserves further research.

- Flexibility exercises: Whether flexibility exercises alone offer any significant benefit for long-term (chronic) back pain is uncertain.

- Retraining deep or core muscles: Studies are finding a link between low back pain and poor motor control of deep muscles in the back and trunk. According to these studies, contraction exercises specifically designed to retrain these muscles may be effective for people with both acute and chronic pain.

It is important for any person who has low back pain to have an exercise program guided by professionals who understand the limitations and special needs of back pain, and who can address individual health conditions.

Negative Effects on the BackImproper or excessive exercise can also cause back pain.

How Exercise Affects the Lungs

People with long-term (chronic) lung problems have difficulty exercising. Shortness of breath is a major limitation in most people, but in about a third, muscle fatigue is an even greater problem. Although exercise does not improve lung function, training helps many people with long-term (chronic) lung disease by helping limb muscles use oxygen effectively, thus improving endurance and reducing breathlessness.

Effects of Exercise on Respiratory Infections (Colds and the Flu)

In people who already have colds, exercise has no effect on the illness' severity or duration. People should avoid strenuous physical activity when they have fevers, muscle aches, or other symptoms of a widespread viral illness.

Effects of Exercise on Asthma

People with asthma who enjoy running should consider using an indoor track, to avoid pollutants and cold winter air. Swimming is particularly beneficial for people with asthma. Yoga practice, which uses stretching, breathing, chest expansion, and meditation techniques may have specific benefits that include stress reduction as well as airway opening.

Exercise-Induced Asthma (EIA)EIA occurs when exercise triggers coughing, wheezing, or shortness of breath. It occurs most often in children and young adults and during intense exercise in cold dry air. EIA is triggered only by exercise. Unlike allergic asthma, there is no long-term increase in airway activity. People who have only EIA do not need long-term maintenance therapy. The warm-up and cool-down periods, which are important for any exercise regimen, may help reduce EIA events. EIA is not a reason to exclude people from physically demanding occupations.

Hints for Reducing EIAEIA occurs only after exercise and is more likely to occur with regularly-paced activities in cold, dry air. The following are some suggestions for reducing the impact of EIA:

- For those with long-term (chronic) asthma, follow the provider's instructions for using long-term control medications, particularly inhaled corticosteroids, when prescribed.

- Warm-up and cool-down periods are important.

- People with EIA might do better with activities that involve short bursts of exercise (tennis, football), rather than with exercises involving long-duration regular pacing (cycling, soccer, and distance running). In winter, indoor exercise is the best. Swimming is particularly desirable because of the humidity.

- When exercising in cold air, breathing through a scarf or through the nose helps warm up the airways.

EIA is distinct from allergic asthma in that it does not produce a long-term increase in airway activity. People who have asthma only when they exercise may be able to control their symptoms with preventive measures, such as warm-up and cool-down exercises.

Effects of Exercise on Emphysema

Walking is the best exercise for people with emphysema. Patients should try to walk 3 to 4 times daily for 5 to 15 minutes each time. Devices that assist ventilation may reduce breathlessness that occurs during exercise.

Strengthening Exercises for the LimbsExercising and strengthening the muscles in the arms and legs helps some people improve their endurance and reduce breathlessness.

Inspiratory muscle training involves exercises and devices that make inhaling (breathing in) more difficult, in order to strengthen breathing muscles. Yoga or martial arts exercises, such as Tai chi, which emphasize breathing techniques and balanced movements, may be particularly beneficial for people with emphysema.

How Exercise Affects Weight

Exercising helps people reduce their weight, maintain weight loss, and fight obesity. Research has shown that women who regularly exercise but do not change their diet can lose significantly more weight than less active women.

Thirty minutes of moderate-intensity exercise may be adequate to maintain cardiovascular health, but it might not prevent weight gain. An hour or more of daily moderate exercise may be needed to promote weight loss. Children may need more activity.

Losing significant weight requires both exercise and calorie restriction. In addition, if a person exercises without dieting, any actual weight loss may be minimal because dense and heavier muscle mass replaces fat. Nonetheless, regardless of weight loss, a fit body will look more toned and be healthier.

People who exercise are more likely to stay on a diet plan. Exercise improves psychological well-being and replaces sedentary habits that usually lead to snacking. Exercise may even act as a mild appetite suppressant.

Exercising without dieting still adds health benefits, maybe even lowering the death rate of overweight, unfit people. People who have trained for a long time may develop more efficient mechanisms for burning fat and are able to stay leaner.

Lifting weights builds muscle, which burns calories more efficiently than other body tissues.

The following are some suggestions and observations on exercise and weight loss:

- The treadmill burns the most calories of standard aerobic machines. Exercise sessions as short as 10 minutes, which are done frequently (about 4 times a day), may be the most successful program for obese people.

- The more strenuous the exercise, the longer the body continues to burn calories before returning to its resting level. This state of fast calorie burning can last from as little as a few minutes after light exercise to as long as several hours after prolonged or heavy exercise.

- Resistance (strength) training is excellent for reducing fat and building muscles. It should be performed 2 or 3 times a week.

- Fidgeting may be very helpful in keeping pounds off. Regular exercise is certainly the best course, but for people who must sit for hours at work, frequently shifting positions while sitting may have some benefit.

- It is important to realize that as people slim down, they burn fewer calories per mile of walking or running. The rate of weight loss slows down, sometimes discouragingly so, after an initial dramatic head start using diet and exercise combinations. People should be aware of this trend and keep adding to their daily exercise routine.

- Changes in fat and muscle distribution may differ between men and women as they exercise. Men tend to lose abdominal fat (which lowers their risk for heart disease faster than reducing general body fat). In women, aerobic and strength training are more likely to result in fat loss in the arms and trunk. However, they do not gain muscle tissue as easily in those areas.

Because obesity is one of the risk factors for heart disease, anyone who is overweight must discuss their exercise program with a physician before starting.

How Exercise Affects Other Conditions

Physical activity makes you healthier. It lowers your risk for cardiovascular disease and reduces bone loss. Physical activity also helps the body use calories more efficiently, which helps you eliminate body fat and lose weight. It also helps you maintain weight loss by increasing your metabolism and reducing your appetite.

People who engage in physical activity of around 150 minutes per week have 33% lower risk of all-cause mortality than physically inactive people.

Effect of Exercise on Cancer

A number of studies have indicated that regular exercise may reduce the risk of breast, colon, lung, bladder, endometrium, kidney, stomach, and esophagus.

Regular exercise may protect against breast cancer. Exercise can help reduce body fat, which in turn lowers levels of cancer-promoting hormones, such as estrogen. The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends engaging in 45 to 60 minutes of physical activity at least 5 days a week.

Exercise can also help women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer and may help reduce the risk of breast cancer recurrence. Studies indicate that both aerobic and weight training exercises benefit the body and the mind, and improve quality of life for breast cancer survivors.

A sedentary lifestyle increases the risk of developing colorectal cancer. Regular exercise may help reduce risk.

Exercise also has a beneficial effect on people receiving treatment for cancer. Aerobic and resistance training can reduce fatigue in patients undergoing chemotherapy or radiation treatments for cancer. Fatigue is a common side effect of such treatments.

In people who have completed their cancer treatments, exercise improves physical well-being and quality of life.

Effects on the Gastrointestinal Tract

Endurance athletes often report stomach problems, such as bloating, diarrhea, and gas, even at rest. Moderate regular exercise, however, might reduce the risk for some intestinal disorders. These disorders include irritable bowel syndrome, indigestion, and diverticulosis. Older people who exercise moderately may have a lower risk for severe gastrointestinal bleeding.

Effects on Neurological Diseases and Mental Decline

Studies have shown that regular exercise, particularly walking, may help reduce one's risk for memory loss or cognitive decline. Epidemiologic studies have found an association between increased exercise and slower rate of functional decline in older adults. To date, there are no clear explanations for this apparent benefit. Aerobic exercise has been linked to improved reaction time in people of all ages.

Exercise seems to improve the physical and emotional well-being of people who already have Alzheimer disease. As little as 60 minutes each week may reduce depression, wandering, and falls.

People with existing neurological diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, and Alzheimer disease, should be encouraged to exercise. Specialized exercise programs that improve mobility are particularly valuable for patients with Parkinson disease. Patients with neurological disorders who exercise have less stiffness, as well as reduction in, and even reversal of, muscle wasting. In addition, the psychological benefits of exercise are extremely important in managing these disorders. Exercise machines, aquatic exercises, and walking are particularly useful.

Effects on Emotional Disorders

In The American Psychiatric Association's guidelines for the treatment of people with major depressive disorder, exercise and other healthy behaviors (good nutrition, sleep hygiene, reducing use of tobacco, alcohol, and other harmful substances) are recommended for helping improve mood symptoms.

Both aerobic exercise and resistance training can help improve mood symptoms for people with depression. Aerobic workouts can raise chemicals in the brain, such as endorphins, adrenaline, serotonin, and dopamine that produce the so-called runner's high. Yoga practice, which involves rhythmic stretching movements and breathing, may help improve and stabilize mood. Meditation may also be helpful.

Although there is little evidence that exercise can correct major depression, studies have suggested benefits in mild-to-moderate depression in adults.

- Older people, depressed people may experience modest benefits from exercise, even in those who do not respond to antidepressants. Simply participating in a group activity may help improve mood.

- Teenagers who are active in sports have a greater sense of well-being than their sedentary peers. The more vigorously they exercise, the better their emotional health.

- Physical inactivity is strongly linked to depression in children 8 to 12 years of age.

- Exercise decreases some of the most troublesome emotional symptoms of menopause. Women who exercise during menopause showed less anxiety, stress, and depression than inactive women with menopause did.

Effect of Exercise on Pregnancy

Moderate exercise in healthy pregnant women does not increase the risk for miscarriage, preterm labor, or rupture of the membrane. Not exercising increases the risk for complications, including low-birth weight babies. Exercising increases the fetal heart rate, which in turn protects the baby.

Healthy women with normal pregnancies should exercise at least 3 times a week, being careful to warm up, cool down, and drink plenty of liquids. Many prenatal calisthenics programs are available.

The following are specific exercises that may benefit the pregnant woman:

- Swimming and water aerobics may be the best option for most pregnant women. Water exercises involve no impact, overheating is unlikely, and swimming face down promotes optimum blood flow to the uterus.

- Performing yoga exercises under the guidance of informed instructors can be very helpful.

- Walking is also beneficial.

To strengthen pelvic floor muscles, women should do Kegel exercises at least 6 times a day. This involves contracting the muscles around the vagina and urethra for 3 seconds 12 to 15 times in a row.

The following precautions are generally recommended for pregnant women who exercise:

- Fit women who have exercised regularly before pregnancy may work out intensely as long as the provider approves and no discomfort occurs. However, excessive exercise can cause undernourishment of the fetus.

- As a rule for previously sedentary, low-risk expectant mothers, the pulse rate should not exceed 70% to 75% of the maximum heart rate, or more than 150 beats per minute. Any sedentary expectant mother should check with her provider before starting an exercise program.

- Vigorous exercise may improve the chances for a timely delivery. All pregnant women, however, should avoid high-impact, jerky, and jarring exercises, such as aerobic dancing, which can weaken the pelvic floor muscles that support the uterus.

- During exercise, women should monitor their temperature to avoid overheating, a side effect that can damage the fetus. (Pregnant women should also not use hot tubs or steam baths, which can cause fetal damage and miscarriage.)

Complications

Exercise may lead to injury. Always exercise with care. Be sure you have clear instructions on how to perform your exercises and how to use any equipment you exercise with.

Injuries from High-Impact Exercise

Competitive running or high-impact aerobics pose a high risk of a number of injuries to the bones and muscle. Injuries to knees, ankles, hips, back, shoulders, and elbows are all possible.

Preventing High-Impact InjuriesThe following may be helpful for preventing injury:

- Wear shock-absorbing footwear with weight-dampening inserts.

- Combine weight lifting with jumping exercises. This may prevent injury by strengthening hamstrings and improving coordination.

- Vary training and alternate easy and harder workouts.

- Be careful to warm up, cool down, and stretch. Flexibility is the key to preventing many muscle strains.

- Take days off now and then. The risk of injury increases when athletes train more than 5 times a week.

Most mild or moderate injuries respond well to a simple, four-step treatment: rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE). This combination works well for both spot injuries and long-term (chronic) problems. Ice packs, which reduce inflammation and pain, can help new injuries, and can be useful for the first few hours after a chronically injured area is exercised. How much or how long to compress the injury is unclear.

Evidence suggests that early movement is helpful, although taping or bracing in people with a recurrent ankle sprain is known to be protective. It may not be helpful in those without a previous ankle injury.Minor injuries, like sprains, may be treated at home if broken bones are not suspected. The acronym RICE can help you remember how to treat minor injuries: "R" stands for rest, "I" is for ice, "C" is for compression, and "E" is for elevation. Pain and swelling should decrease within 48 hours. Gentle movement may help, but pressure should not be put on a sprained joint until pain is completely gone. This can take up to a few weeks.

Heat, ultrasound, whirlpool, and massage may speed healing if applied a day or two after the initial injury, or for warm-up before another workout session.

Female Athlete Triad

Some young female athletes who exercise very intensely, and are subject to intense pressure to remain thin, are at risk for a syndrome known as the female athlete triad. This combination of symptoms includes loss of menstruation, eating disorders, and osteoporosis. Eating disorders among young female athletes are estimated at 15% to 62%. Women at higher risk include ballet dancers, gymnasts, and divers. Continued intense exercise causes a stress response in which estrogen (the primary female hormone) levels are reduced. Estrogen loss can lead to infertility and osteoporosis. Iron loss and anemia may also be a problem in women who exercise frequently, even at moderate intensity. A provider should be consulted for any of these concerns.

Improper Mechanics and Its Effect on the Back and Shoulders

Incorrect movements can literally cause mechanical problems in the muscles. These problems are usually the result of improper exercise instruction, and lack of attention. A single jerky golf swing, or the incorrect use of exercise equipment (such as free weights, nautilus, and rowing machines), can cause serious back injuries.

Between 30% to 70% of cyclists feel low back pain. Pain may be improved by adjusting the angle of the bicycle seat.

Dehydration

Everyone should drink lots of fluid during intense exercise. Thirst is often a poor indicator of dehydration in people who exercise, particularly older people. During a tough workout in a hot environment, the body can lose 2 liters of fluid per hour through sweat.

Anyone who exercises intensely should take the following precautions:

- Drink 6 to 8 ounces (180 to 240 mL) of fluid about 15 minutes before a workout, and then pause regularly during exercise to drink more.

- Water is the best choice for replenishing body fluids. Glucose-sodium-potassium solutions, the so-called "sports drinks," which promise instant energy, appear to be no better than water at improving endurance during prolonged intense running.

- Caffeinated beverages like coffee and soft drinks give short bursts of energy, but can actually cause fluid loss. Caffeine before a workout has been shown to temporarily raise blood pressure, and reduces blood flow to inactive limbs.

- Avoid salt tablets. They can increase your risk of dehydration. It is better to drink beverages that have some sodium in them than to take it in concentrated form.

Contrary to popular belief, drinking fluids will not cause cramps. Drinking enough, in fact, helps prevent the painful involuntary muscle spasms that sometimes occur during exercise.

Hyperthermia (Overheating)

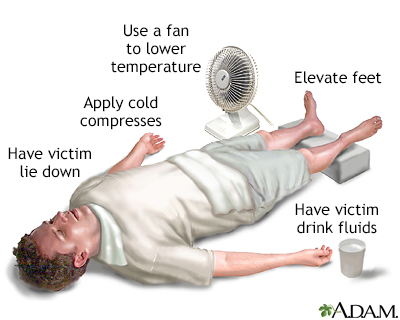

Overheating, or hyperthermia, can be a problem with hard exercise, or when working out in hot weather. Overheating can cause mild to life-threatening conditions. Heat exhaustion, a moderate form of hyperthermia, is characterized by the following symptoms:

- Lightheadedness, nausea, headache, hyperventilation, fatigue, and loss of concentration

- A high temperature (above 103ºF [39.4ºC]), possibly accompanied by complaints of chills and clammy skin

Individuals should rest in a cool, dry place, drink plenty of fluids, and bring down their body temperature with ice packs pressed against the skin.

Heat StrokeHeat stroke is the most dangerous complication of hyperthermia. The victim may suddenly stop sweating, after which symptoms such as altered consciousness, seizures, and even coma may quickly follow. Heat stroke is a medical emergency and requires immediate cooling of the victim in an ice-water bath or with ice packs. Complications from exercising in high temperatures may persist as late as the following day, even if the weather has cooled down.

Try these tips to help prevent heat-related illness:

- Drink plenty of fluids. Drink before, during, and after your workout. Drink even if you do not feel thirsty. You can tell you are getting enough if your urine is light or very pale yellow.

- Do not drink alcohol, caffeine, or drinks with a lot of sugar, such as soda. They can cause you to lose fluid. Water is your best choice for less-intense workouts. If you will be exercising for a couple of hours, you may want to choose a sports drink. These replace salts and minerals as well as fluids. Choose lower-calorie options. They have less sugar.

- Make sure the water or sports drinks are cool, but not too cold. Very cold drinks may cause stomach cramps.

- Limit your training on very hot days. Try training in early morning or later at night.

- Choose the right clothing for your activity. Lighter colors and wicking fabrics are good choices.

- Protect yourself from direct sun with sunglasses and a hat. Do not forget sunscreen (SPF 15 or higher).

- Rest often in shady areas or try to stay on the shady side of a walking or hiking trail.

Frostbite and Hypothermia

Precautions are also necessary in cold weather. When exercising in winter dress in layers, including gloves and socks, which create insulated air pockets that trap heat. In cold weather, wear shoes with less ventilation than those worn in the summer. Fingers, toes, ears, and nose are most susceptible to frostbite. Frostbite progresses from stinging or aching to numbness. Fingers and toes may become white. Soaking the hands and feet in warm water can help, but only once there is no risk of refreezing, since a second bout of frostbite after thawing can quicken tissue damage.

Get plenty of food and fluids. You need both food and fluids to fuel your body and keep you warm. If you skimp on either, you increase your risk for cold weather injuries. Eating foods with carbohydrates give you quick energy. If you are only out for a short time, you may want to carry a snack bar to keep your energy going. If you are out all day skiing, hiking, or working, be sure to also bring food with protein and fat to fuel you during many hours. Drink plenty of fluids before and during activities in the cold. You may not feel as thirsty in cold weather, but you still lose fluids through your sweat and when you breathe.

Hypothermia can be life-threatening and can occur even after long exposure to temperatures that are above freezing. The condition is characterized by extreme fatigue, mental confusion, apathy, and a lack of coordination. The victim should be warmed as soon as possible with blankets, body heat, and warm fluids.

Motivation

Motivation, or a lack thereof, is one reason many people stop exercising. Here are some tips for avoiding burnout:

- Think of exercise as a menu rather than a prescription. Choose a number of different physical activities that are personally enjoyable such as sports, dancing, or biking. Although experts say you should get 30 minutes of aerobic exercises at least 5 times a week, those times can be divided into shorter periods -- such as 10 minute sessions. In addition, people can achieve health benefits from other exercise programs, including weight training, yoga, or Tai chi.

- Stick to a prepared schedule and record progress.

- Develop an interest or hobby that requires physical activity.

- Adopt simple routines such as climbing the stairs instead of taking the elevator, walking instead of driving to the local newsstand, or canoeing instead of zooming along in a powerboat.

- Try cross training (alternating between exercise types). Studies suggest it is more beneficial than focusing only on one form of exercise.

- Exercise with friends.

- Join a gym or take classes. Many affordable programs are available.

- For those who can afford them, personal trainers can be very helpful and are available in many gyms and exercise clubs. Personal trainers without any connection to a well-reputed gym or fitness club should be certified by a major fitness organization, such as the Aerobics and Fitness Association of America (AFAA) or the American Council on Exercise (ACE).

- Exercise videos may also be helpful, but people should be sure they are suited to their individual age and health needs, and bear the AFAA seal.

- Consider getting a dog. Studies show that dog owners walk up to twice as much as those who do not own a dog. Regular walking is a good way to improve health.

Motivation factors may differ by gender. In one study, weight loss was the greatest motivator to exercise for women, and muscle tone was the primary motivator for men. Unfortunately, effects on appearances may take a long time to show, discouraging people from continuing an exercise program even though their health is improving.

Motivating Children and Adolescents

Overweight among children and adolescents have now become an epidemic in the United States. Children should be vigorously active for at least 20 to 60 minutes for 3 to 5 days a week. Parents and schools must be imaginative and rigorous in encouraging children to exercise.

Children who engage in moderate to vigorous physical activities are likely to have lower blood pressures, lower LDL (bad) cholesterol levels, and smaller waist circumferences than children who are less active. Lifestyle interventions can yield benefits for weight control and heart health.

Role of ParentsParents must make conscious efforts to limit sedentary activities, and to encourage physical ones for their children. This includes monitoring the time children spend on the computer, smartphone, in front of the TV, or playing video games. In fact, decreasing the amount of time children spend in front of a screen leads to a reduction in their body mass index (BMI), an indicator of obesity. This loss in BMI in children is the result of increased activity and reduced snacking.

Parents should suggest different forms of entertainment. Even children who aren't interested in joining a Little League team may enjoy a round of catch with their parents, walking in the park, or swimming in a local lake.

Role of SchoolsEarly school physical education (PE) programs can make a significant difference, and the earlier these routines are learned the more likely they will be carried forth into a healthy adulthood. There are also physical benefits to PE programs that are just now becoming known. For example, a study found that incorporating jumping exercises into an elementary school's PE program increased children's bone densities, a measure of bone strength. In general, school-based physical activity promotion programs have some positive effects on habits and health, such as reduced television viewing and lowered cholesterol. So far however, studies have not proven that these programs boost overall activity levels.

Schools should emphasize team cooperation or individual improvement and self-mastery. Studies have shown that people tend to give up more quickly and feel less competent if their perceptions of success are based only on comparison to their peers.

People mature at different rates, and there seems to be a genetic component to coordination, strength, speed, and one's response to resistance exercise. Nonetheless, everyone should strive to be as fit as they possibly can, given their strengths and limitations.

Stages for Adopting Healthy Behavior

The decision to adopt a healthier behavior, whether it is more exercise, weight loss, or quitting smoking, is not as simple as just deciding to do it. Behavior change expert James Prochaska and his colleagues outlined a theory, which has been supported by numerous studies, showing that people cycle through a variety of stages before a new behavior is successfully adopted over the long-term. It may help you to understand how this works. As you read the description of each stage -- specifically as it relates to exercise -- you may find yourself nodding and saying to yourself, "Yes, that's me!"

Stage 1: Pre-ContemplationPeople at this stage have no plans or desire to exercise. They are not even considering exercising. They are generally unaware of the specific benefits that exercise can bring -- exercise may seem more like a hassle than something worth doing. Or, they may simply have "failed" in the past and have given up.