Urinary tract infection - InDepth

Cystitis - InDepth; UTI - InDepth; UTIs - InDepth; Bladder infection - InDepth; UTI - InDepth; Cystitis - bacterial - InDepth; Pyelonephritis - InDepth; Kidney infection - InDepthAn in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of urinary tract infections.

Highlights

Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs)

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are a common type of infection typically caused by bacteria (most often E. coli). Cystitis is an infection of the bladder (lower urinary tract infection) caused by bacteria that travel up the urethra to the bladder. Pyelonephritis is an infection of the kidneys and ureters (upper urinary tract infection), a much more serious condition.

Risk Factors

Women are more susceptible to UTIs than men, and their infections tend to recur. One reason is that the urethra (the tube that carries urine away from the bladder) is shorter in women than in men. Sexual intercourse also increases a woman's risk of developing UTIs. Contraceptive spermicides and diaphragms are additional risk factors. When women reach menopause, the decrease in estrogen thins the lining of the urinary tract, which increases susceptibility to bacterial infections.

Pregnancy does not increase the risk of getting a UTI, but it can increase the risk of developing a serious infection that could potentially harm the mother and fetus. Pregnant women should report any symptoms of UTIs to their doctors, and should get screened and treated for asymptomatic bacteriuria (presence of significant numbers of bacteria in the urine without symptoms).

Symptoms

Symptoms of UTIs may include:

- Strong urge to urinate frequently, even immediately after the bladder is emptied

- Painful burning sensation when urinating

- Discomfort, pressure, or bloating in the lower abdomen

- Pain in the pelvic area or back

- Cloudy or bloody urine, which may have a strong smell

- Fever

A urine test can determine if these symptoms are caused by a bacterial infection. Older people may have a urinary tract infection but have few or no symptoms.

Treatment

Antibiotics are used to treat bacterial UTIs. Most cases of UTIs clear up after a few days of drug treatment, but more severe cases may require several weeks of treatment.

Guidelines recommend using nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole as first-line antibiotic treatments for UTIs. Fluoroquinolones (such as ciprofloxacin) are now only recommended when other antibiotics are not appropriate.

Cranberries for UTI PreventionCranberry juice appears to offer little benefit for preventing recurrent UTIs, according to a review by the Cochrane Collaboration. Other studies have suggested that cranberry products may be helpful by preventing harmful bacteria from attaching and sticking to urinary tract cells.

Male Circumcision and UTIsBabies rarely get UTIs but when they do, these infections are much more common in boys than in girls. A recent policy statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) states that boys who are circumcised are less likely to get UTIs during their first year of life than uncircumcised boys. While noting the potential health benefits of male circumcision (including reduced risks for acquiring sexually transmitted diseases), the AAP recommends that the decision to circumcise should be left to parents, in consultation with their child's doctor.

Introduction

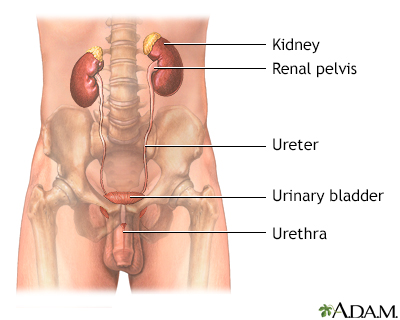

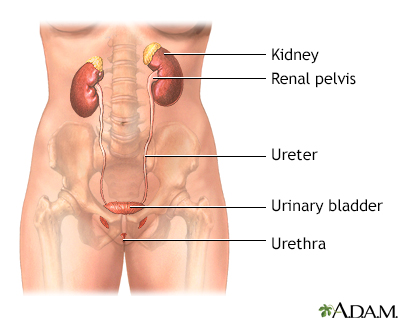

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is a condition in which one or more parts of the urinary system (the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra) become infected. UTIs are among the most common of all bacterial infections and can occur at any time of life. Nearly 95% of cases of UTIs are caused by bacteria that typically multiply at the opening of the urethra and travel up to the bladder. Much less often, bacteria spread to the kidney from the bloodstream.

The male and female urinary tracts are similar except for the length of the urethra.

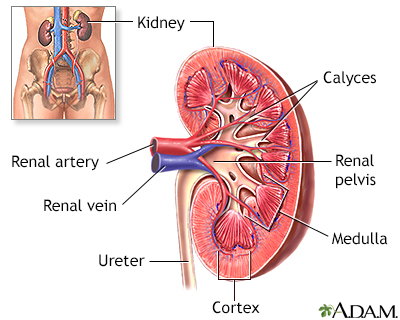

The Urinary SystemThe urinary system helps maintain proper water and salt balance throughout the body and also expels urine from the body. It is made up of the following organs and structures:

- The two kidneys, located on each side below the ribs and toward the middle of the back, play a major role in this process. They filter waste products, water, and salts from the blood to form urine.

- Urine passes from each kidney to the

bladder

through thin tubes calledureters

. - Ureters empty the urine into the bladder, which rests on top of the

pelvic floor

. The pelvic floor is a muscular structure similar to a sling running between the pubic bone in front to the base of the spine. - The bladder stores the urine. When the bladder becomes filled, the muscle in the wall of the bladder contracts, and the urine leaves the body via another tube called the

urethra

. In men the urethra is enclosed in the penis. In women, the urethra is short, which explains the significantly higher risk for UTIs.

Infection does not always occur when bacteria are introduced into the bladder. A number of defense systems protect the urinary tract against infection-causing bacteria:

- Urine functions as an antiseptic, washing potentially harmful bacteria out of the body during normal urination. (Urine is normally sterile, that is, free of bacteria, viruses, and fungi.) Urine is also slightly acidic (low pH), which also inhibits bacterial growth.

- The ureters join into the bladder in a manner designed to prevent urine from backing up into the kidney when the bladder squeezes urine out through the urethra.

- The prostate gland in men secretes infection-fighting substances.

- The immune system defense mechanisms employ cells of the bladder lining, immune cells, and antibacterial substances secreted in the mucous lining of the bladder to eliminate many organisms.

- In healthy women, the vagina is colonized by lactobacilli, beneficial microorganisms that maintain a highly acidic environment (low pH) that is hostile to other bacteria. Lactobacilli produce hydrogen peroxide, which helps eliminate bacteria and reduces the ability of Escherichia coli (E coli) to adhere to vaginal cells. (E coli is the major bacterial culprit in urinary tract infections.)

UTIs are generally classified as:

- Uncomplicated or complicated, depending on the factors that trigger the infections

- Primary or recurrent, depending on whether the infection is occurring for the first time or is a repeat event

Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs)

Uncomplicated UTIs are due to a bacterial infection, most often caused by E coli. UTIs affect women much more often than men.

CystitisCystitis, or bladder infection, is the most common UTI. It occurs in the lower urinary tract (the bladder and urethra) and is much more common in women. In most cases, the infection is brief and acute and only the inner surface of the bladder is infected. Deeper layers of the bladder may be harmed if the infection becomes persistent, or chronic, or if the urinary tract is structurally abnormal.

Pyelonephritis (Kidney Infection)Sometimes, the infection spreads to the upper urinary tract (the ureters and kidneys). This is called pyelonephritis, or more commonly, a kidney infection.

Complicated Urinary Tract Infections

Complicated infections, which occur in men and women of any age, are also caused by bacteria but they tend to be more severe, more difficult to treat, and more likely to recur. They are often the result of:

- An anatomical or structural abnormality that impairs the ability of the urinary tract to clear out urine and therefore bacteria

- Catheter use in the hospital setting or long-term indwelling catheter in the outpatient setting

- Bladder and kidney dysfunction, or kidney transplant (especially in the first 3 months after transplant)

- Immunocompromised state caused by other conditions (such as AIDS, cancer, or following organ transplantation)

Recurrences can occur in people with complicated UTI if the underlying structural, anatomical, or immune abnormalities are not corrected.

Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections

Most women who have had an uncomplicated UTI have occasional recurrences. Many of these women get another infection within a year of the previous one. A much smaller number of women have ongoing, recurrent urinary tract infections, which follow the resolution of a previously treated or untreated episode.

Recurrence is often categorized as either reinfection or relapse:

-

Reinfection.

Most cases of recurring UTIs are reinfections. A reinfection occurs several weeks after antibiotic treatment has cleared up the initial episode. It can be caused by the same bacterial strain that caused the original episode or a different one. The infecting organism is usually introduced from fecal matter and moves up through the urinary tract. -

Relapse.

Relapse is the less common form of recurrent UTI. It is diagnosed when a UTI recurs within 2 weeks of treatment of the first episode and is due to treatment failure. Relapse usually occurs in kidney infection (pyelonephritis) or is associated with obstructions such as kidney stones, structural abnormalities or, in men, chronic prostatitis.

Asymptomatic Urinary Tract Infection (Asymptomatic Bacteriuria)

An asymptomatic UTI (also called asymptomatic bacteriuria) is when a person has no symptoms of infection but has a significant number of bacteria that have colonized the urinary tract. The condition is harmless in most people and rarely persists, although it does increase the risk for developing symptomatic UTIs.

Screening and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria is not usually necessary except for the following people:

-

Pregnant women.

Pregnant women with asymptomatic bacteriuria have an increased risk of acute pyelonephritis in their second or third trimester. Therefore, they need screening and treatment for this condition. Guidelines recommend that pregnant women be screened for asymptomatic bacteriuria at 12 to 16 weeks gestation or at the first prenatal visit, if later. -

People undergoing urologic surgery (such as prostate surgery in men).

The presence of an infection during surgery can lead to serious consequences.

Causes

Bacteria that cause UTIs include:

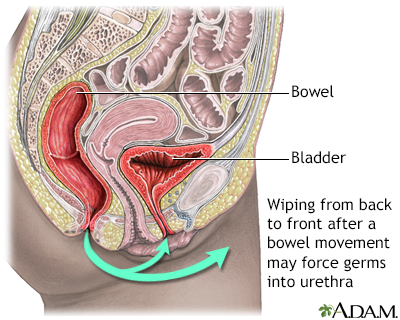

- Escherichia (E) coli is responsible for more than 80% of all UTIs and for most uncomplicated cystitis cases in women, especially younger women. E coli is generally a harmless microorganism originating in the intestines. It is usually found in feces (stool). The strains of E coli that cause UTIs have special properties that make it easier for them to live in and infect the urinary tract. These strains are called uropathogenic. If uropathogenic E coli (UPEC) spread to the vaginal opening, they may invade and colonize the bladder, causing an infection. The spread of E coli to the vaginal opening most commonly occurs when women wipe themselves from back to front after urinating, or after sexual activity.

- Staphylococcus saprophyticus accounts for 5% to 15% of UTIs, mostly in younger women.

- Klebsiella species, Proteus mirabilis, and Enterococci account for most of the remaining bacterial organisms that cause UTIs. They are generally found in UTIs in older women.

- Rare bacterial causes of UTIs include Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis, which are typically harmless organisms.

Organisms in Severe or Complicated Infections

- The bacteria that cause kidney infections (pyelonephritis) are generally the same bacteria that cause cystitis. There is some evidence that the E. coli strains causing pyelonephritis are more virulent (able to spread and cause illness).

- Complicated UTIs that are related to physical or structural conditions are generally caused by a wider range of organisms. E. coli is still the most common organism, but others include Klebsiella, Citrobacter species, and P. mirabilis.

- Fungal organisms, such as Candida species can cause UTIs. (Candida albicans causes the "yeast infections" that also occur in the mouth, digestive tract, and vagina.)

- Other bacteria associated with complicated or severe infections include Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter, and Serratia species as well as gram-positive organisms (including Enterococci species).

Bacterial Strains in Recurrent UTIs

Recurring infections, as opposed to reinfection, are often caused by different bacteria than those that caused a previous or first infection.

Acidity and Infection Resistance

Changes in the amount or type of acid within the genital and urinary tracts contribute to lowering the resistance to infection. For example, beneficial organisms called lactobacilli increase the acidic environment in the female urinary tract and thereby reduce the risk of infection.

Risk Factors

UTIs are far more common among women than among men. Most women will develop a UTI at some time in their lives, and many will have recurrences.

Specific Risk Factors in Women

Structure of the Female Urinary TractIn general, the higher risk for UTIs in women is mostly due to the shortness of the female urethra, which is about 1.5 inches (4 centimeters) compared to 8 inches (20 centimeters) in men. Bacteria from the vagina or fecal matter at the anal opening can be easily transferred to the opening of the urethra.

The female and male urinary tracts are similar except for the length of the urethra.

Sexual ActivityFrequent or recent sexual activity is the most important risk factor for UTIs in young women. Nearly 80% of all UTIs in premenopausal women occur within 24 hours of intercourse. UTIs are very rare in celibate women. However, UTIs are not sexually transmitted infections.In general, it is the physical act of intercourse itself that produces conditions that increase susceptibility to the UTI bacteria, with some factors increasing the risk. For example, women having sex for the first time or who have intense or frequent sex are at risk for a condition called "honeymoon cystitis."

Certain types of contraceptives can also increase the risk of UTIs. In particular, women who use diaphragms tend to develop UTIs. The spring-rim of the diaphragm can bruise the area near the bladder, making it susceptible to bacteria. Spermicidal foam or gel used with diaphragms, and spermicidal-coated condoms, also increase susceptibility to UTIs. Most spermicides contain nonoxynol-9, a chemical that is associated with increased UTI risk.

PregnancyIn pregnant women, the presence of asymptomatic bacteriuria is associated with an increased risk of kidney infection, which can cause early labor and other serious pregnancy complications. For this reason, pregnant women should be screened and treated for asymptomatic bacteriuria. Pregnant women are more susceptible to kidney infection because as the uterus enlarges it compresses the ureters and bladder. This causes urine to back up into the kidney, increasing the risk of bacterial infection.

MenopauseThe risk for UTIs, both symptomatic and asymptomatic, is highest in women after menopause. This is primarily due to a decrease in estrogen, which thins the walls of the urinary tract and reduces its ability to resist bacteria. Estrogen loss can also reduce certain immune factors in the vagina that help block E. coli from attaching to vaginal cells. For some women, topical estrogen therapy helps restore healthy bacteria and reduce the risk of recurrent UTIs. (Oral hormone replacement therapy is not helpful for UTIs.)

Other aging-related urinary conditions, such as urinary incontinence, can increase the risk for recurrent urinary tract infections.

AllergiesWomen who have skin allergies to ingredients in soaps, vaginal creams, bubble baths, or other chemicals that are used in the genital area are at increased risk for UTIs. In such cases, the allergies may cause small injuries that can introduce bacteria.

Antibiotic UseAntibiotics often eliminate lactobacilli, the protective bacteria, along with harmful bacteria. This can cause an overgrowth of E. coli in the vagina.

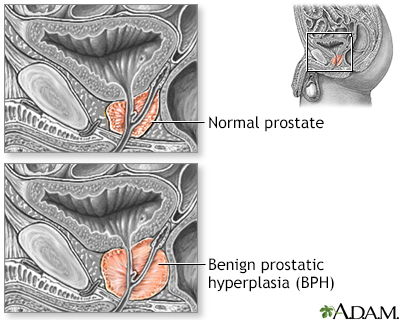

Specific Risk Factors in Men

Men become more susceptible to UTIs after the age of 50, when they begin to develop prostate problems. Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), enlargement of the prostate gland, can produce obstruction in the urinary tract and increase the risk for infection. In men, recurrent UTIs are also associated with prostatitis, an infection of the prostate gland. Although UTIs are less common in men, they can cause more serious problems in men than in women. Men with UTIs are more likely to require hospitalization than women.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

An in-depth report about the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

| Read Article Now | Book Mark Article |

Specific Risk Factors in Children

UTIs are rare during infancy but they are much more common in boys than in girls. Boys who are circumcised are far less likely than uncircumcised boys to develop UTIs by the time they are 1 year old. After the age of 2 years, UTIs are more common in girls. As with adults, E. coli is the most common cause of UTIs in children.

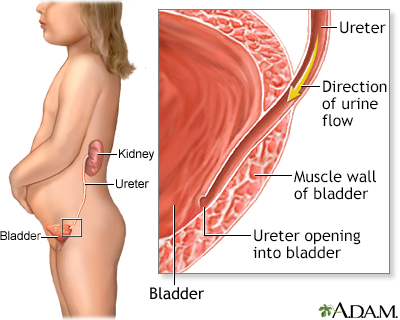

Vesicoureteral Reflux (VUR)Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is the cause of up to half of the UTIs that occur during childhood. VUR also puts children at risk for UTI recurrence.

VUR is a condition in which the urine backs up into the kidneys. Normally, urine travels from the kidneys through the ureters, and into the bladder. When the bladder becomes filled, the muscle in the bladder wall contracts, and the urine leaves the body through another tube called the urethra. There is a valve-like mechanism at the point where the ureters join the bladder at an angle, through a tunnel under the mucosal lining. The job of these valves is to keep urine from flowing backward towards the kidneys when the bladder contracts. If the ureters enter the bladder through a shorter tunnel then these valves do not work well and urine may remain in the bladder where bacteria can grow. The backflow of urine may also carry any infection from the bladder up into the kidneys.

A child may be:

- Born with problems with these valves.

- Born with defects in the anatomy of the lower urinary tract that cause reflux.

- Have problems with nerve supply or function of the bladder, such as spina bifida.

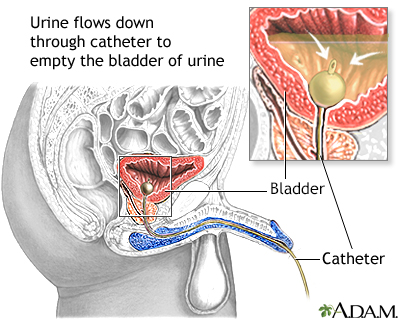

Catheterization and UTI Risk

Most UTIs that develop in hospitalized people are due to urinary catheters. The longer any urinary catheter is in place, the higher the risk for growth of bacteria and an infection. In most cases of catheter-induced UTIs, there are no symptoms. However, due to the risk for infection spreading, anyone requiring a catheter should be screened for infection. Catheters should be used only when necessary and should be removed as soon as possible.

All older adults who are immobilized, catheterized, or dehydrated are at increased risk for UTIs. Nursing home residents, particularly those who are incontinent, are at very high risk.

Medical Conditions that Increase the Risk of UTIs

DiabetesDiabetes (type 1 and type 2) puts women at significantly higher risk for asymptomatic bacteriuria. The longer a woman has diabetes, the higher the risk. Control of blood sugar does not affect the risk for this condition. Diabetes damages nerves that assist with bladder function, leading to problems in emptying and controlling the bladder. As a result, urinary tract infections in people with diabetes are more frequent, more difficult to treat, and associated with more severe infections that can affect the kidneys. UTIs caused by fungi are also more likely to occur in people with diabetes.

Kidney ProblemsNearly any kidney disorder, including kidney stones, increases the risk for complicated UTIs.

Neurogenic BladderA number of brain and nerve disorders can affect the nerves of the bladder and cause problems with the ability to empty the bladder and control urine leakage. Multiple sclerosis, stroke, spinal cord injury, and diabetic neuropathy are common examples.

Immune System ProblemsPeople with immunocompromised systems, such as those who have HIV/AIDS or who are undergoing treatment for cancer, are at increased risk for all types of infections, including UTIs and pyelonephritis.

Urinary Tract AbnormalitiesSome people have structural abnormalities of the urinary tract that cause urine to stagnate or flow backward into the upper urinary tract. A prolapsed bladder (cystocele) can result in incomplete urination so that urine collects, creating a breeding ground for bacteria. Tiny pockets called diverticula sometimes develop inside the urethral or bladder wall and can collect urine and debris, further increasing the risk for infection.

Complications

In most cases, UTIs are annoyances that cause urinary discomfort. However, if left untreated, UTIs can develop into very serious and potentially life-threatening kidney infections (pyelonephritis) that can permanently scar or damage the kidneys. The infection may also spread into the bloodstream (called sepsis) and elsewhere in the body.

UTIs in pregnant women pose serious health risks for both mother and child. UTIs that occur during pregnancy have a higher than average risk of developing into kidney infections. Any pregnant woman who suspects she has a UTI should immediately contact her doctor. Many doctors recommend that women receive periodic urine testing throughout their pregnancies to check for signs of bacterial infection.

In some adults, recurrent UTIs may cause scarring in the kidneys, which over time can lead to renal hypertension and to kidney failure, a serious condition that requires lifelong treatment with dialysis or kidney transplant. Most of these adults with kidney damage have other predisposing diseases or structural abnormalities. Recurrent UTIs almost never lead to progressive kidney damage in otherwise healthy people.

Scarring and future kidney problems are concerns for children who experience severe or multiple kidney infections.

Symptoms

Symptoms of lower UTIs usually begin suddenly and may include one or more of the following signs:

- The urge to urinate frequently, which may recur immediately after the bladder is emptied.

- A painful burning sensation when urinating. If this is the only symptom, then the infection is most likely urethritis, an infection limited to the urethra.

- Discomfort or pressure in the lower abdomen. The abdomen can feel bloated.

- Pain in the pelvic area or back.

- The urine often has a strong smell, looks cloudy, or contains blood. This is a sign of

pyuria

, a high white blood cell count in the urine, and is a very reliable indicator of UTIs. - Occasionally, fever develops.

Symptoms of Severe Infection in the Kidney (Pyelonephritis)

Symptoms of kidney infections tend to affect the whole body and be more severe than those of cystitis (inflammation of the bladder and ureters). They may include:

- Symptoms of lower UTIs that persist longer than a week. Sometimes lower UTI symptoms may be the only signs of kidney infection. People at highest risk for such "silent" upper urinary tract infections include people with diabetes, impaired immune systems, or a history of relapsing or recurring UTIs.

- An increased need to urinate at night.

- Chills and persistent fever (typically lasting more than 2 days).

- Pain in the flank (pain that runs along the back at about waist level).

- Vomiting and nausea.

- Fever.

Symptoms of UTIs in Infants and Toddlers

UTIs in infants and preschool children tend to be more serious because they are more likely to involve the kidneys. Older children are more likely to have lower UTIs and standard symptoms. Infants and young children should always be checked for UTIs if the following symptoms are present:

- A persistent high fever of otherwise unknown cause, particularly if it is accompanied by signs of feeding problems, listlessness, and fatigue.

- Painful, frequent, and foul-smelling urine. (Parents are generally unable to identify a UTI just by the smell of their child's urine. Medical tests are needed.)

- Cloudy urine. (If the urine is clear, the child most likely has some other ailment, although it is not absolute proof that the child is UTI-free.)

- A recurrence of bedwetting or poor urine control during the day in a child who previously had bladder control.

- Abdominal and low back pain.

- Vomiting and abdominal pain (usually in infants).

Symptoms of UTIs in Older People

The classic lower UTI symptoms of pain, frequency, or urgency and upper tract symptoms of flank pain, chills, and tenderness may be absent or altered in older people with UTIs.

Symptoms of UTIs that may occur in seniors but not in younger adults include mental changes or confusion, nausea or vomiting, abdominal pain, or cough and shortness of breath. A preexisting health condition may further confuse the picture and make diagnosis difficult.

Diagnosis

A doctor can confirm if you have a UTI by testing a sample of your urine. For some younger women who are at low risk of complications, the doctor may not order a urine test and may diagnose a UTI based on the description of symptoms.

Urine Tests

UrinalysisA urinalysis is an evaluation of various components of a urine sample. It involves looking at the urine color and clarity, using special dipsticks to do different chemical tests, and possibly inspecting some of the urine underneath a microscope. A urinalysis usually provides enough information for a doctor or nurse to start treatment. Besides the visual examination of color and clarity, urinalysis can detect properties and contents of urine, including:

- pH

- Urine specific gravity (concentration)

- Presence of protein, glucose (sugar), or other metabolic products

- Bacteria or other microorganisms

- Cells (red blood cells, white blood cells, cells from the urinary tract)

- Casts

- Crystals

If necessary, the doctor may order a urine culture, which involves incubating and growing the bacteria contained in the urine. A urine culture can help identify the specific bacteria causing the infection and determine which type of antibiotics to use for treatment. A urine culture may be ordered if the urinalysis does not show signs of infection but the doctor still suspects a UTI is causing the symptoms. It may also be ordered if the doctor suspects complications from the infection. The results of a urine culture are typically available after 2 days.

Clean-Catch SampleTo obtain an untainted urine sample, doctors usually request a so-called midstream, or clean-catch, urine sample. Here are some tips for providing an accurate sample:

- Wash your hands thoroughly, and then wash the penis or vulva and surrounding area four times, with front-to-back strokes, using a new soapy sponge each time.

- Urinate a small amount into the toilet for a few seconds and then stop. (Women should hold open with one hand the folds of the labia while urinating.)

- Position the container to catch the middle portion of the stream. Urinate until the collection cup is halfway full (about 2 ounces).

- Remove the cup and urinate the remainder of your flow into the toilet.

- Securely screw the container cap in place without touching the inside of the rim and place it where directed. The sample will be given to the doctor or sent to the laboratory for analysis.

Some people (small children, elderly people, or hospitalized people) cannot provide a urine sample. In such cases, a catheter may be inserted into the bladder to collect urine. This is the best method for providing a contaminant-free sample, but it carries a risk of introducing or spreading infection.

Other Tests

If the infection does not respond to treatment, the doctor may order other tests to determine what is causing the symptoms. Imaging tests such as ultrasound and computed tomography (CT scan) may help identify:

- Serious and recurrent cases of pyelonephritis

- Structural abnormalities

- Obstruction (such as kidney stones) or abscess

- Possible obstruction or vesicoureteral reflux in children ages 2 to 24 months

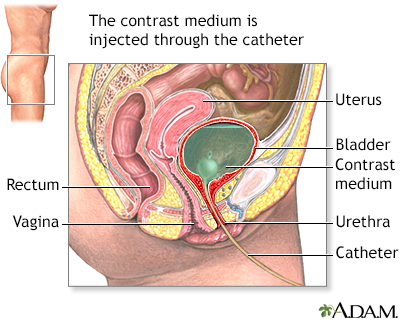

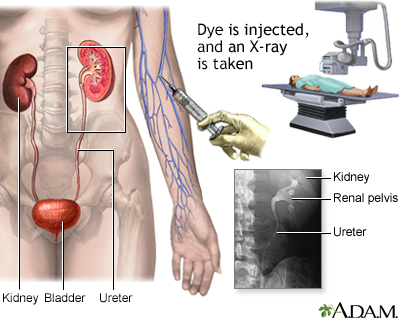

Special x-rays can be used to screen for structural abnormalities, urethral narrowing, or incomplete emptying of the bladder:

Voiding cystourethrogram

is an x-ray of the bladder and urethra. To obtain a cystourethrogram, a dye, called contrast material, is injected through a catheter inserted into the urethra and passed through the bladder.Intravenous pyelogram

(IVP) is an x-ray of the kidney. For a pyelogram, the contrast matter is injected into a vein and eliminated by the kidneys. In both cases, the dye passes through the urinary tract and reveals any obstructions or abnormalities on x-ray images. This test is rarely done anymore and has largely been replaced by CT scan.CT scan

(computerized tomography) is a special x-ray that can evaluate the entire urinary tract as well as the rest of the abdomen. IV dye is injected into a vein, but the test is sometimes done without dye, especially when looking for kidney stones.

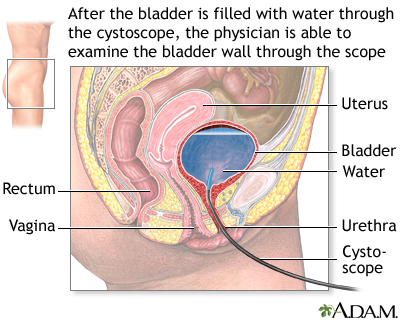

Cystoscopy

Cystoscopy is used to detect structural abnormalities, interstitial cystitis (painful bladder syndrome), or masses that might not show up on x-rays during an IVP. The person is given a local anesthetic jelly and the bladder is filled with water. The procedure uses a cystoscope, a flexible, tube-like instrument that the urologist inserts through the urethra into the bladder.

Blood Cultures

If the person has a fever or other signs of a serious infection, the doctor will order blood cultures to determine if the infection has entered the bloodstream and is threatening other parts of the body.

Ruling Out Conditions with Similar Symptoms

About half of women with symptoms of a UTI actually have some other condition, such as irritation of the urethra, vaginitis, interstitial cystitis, or sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Some of these problems may also accompany or lead to UTIs.

VaginitisVaginitis is an inflammation of the vagina. It is commonly by a yeast infection (candidiasis) or bacterial infection (vaginosis). Occasionally, the infection causes frequent urination, mimicking cystitis. The typical symptoms of vaginitis are itching and an abnormal discharge.

Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs)Women with painful urination whose urine does not exhibit signs of bacterial growth in culture may have an STD. The most common microorganism is Chlamydia trachomatis. Other STDs that may be responsible for similar symptoms include gonorrhea and genital herpes.

Interstitial CystitisInterstitial cystitis (IC), also known as painful bladder syndrome, is an inflammation of the bladder wall that occurs almost predominantly in women. Symptoms are very similar to cystitis, but no bacteria are present. Pain during sex is a very common complaint in these patients, and stress may intensify symptoms. It may be diagnosed if symptoms of a UTI are present but the urine cultures are repeatedly negative.

Kidney StonesThe pain of kidney stones along with blood in the urine can resemble the symptoms of pyelonephritis. However, there are no bacteria present with kidney stones.

Thinning Urethral and Vaginal WallsAfter menopause, the vaginal and urethral walls become dry and fragile, causing pain and irritation that can mimic a UTI.

Disorders in Children that Mimic UTIsProblems that might cause painful urination in children include reactions to chemicals in bubble bath, diaper rashes, and infection from the pinworm parasite.

Prostate Conditions in MenProstate conditions, including prostatitis (inflammation of the prostate) and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), can cause symptoms similar to UTIs.

Poorly-controlled DiabetesExcess sugar in the urine can have a diuretic effect, thereby causing frequent urination.

Treatment

Antibiotics are the main treatment for UTIs. A variety of antibiotics are available, and choices depend on many factors, including whether the infection is complicated or uncomplicated or primary or recurrent. Treatment decisions are also based on the type of person (man or woman, a pregnant or nonpregnant woman, child, hospitalized or nonhospitalized person, or person with diabetes).

Due to the recent increase of drug-resistant bacteria, a doctor may also select an antibiotic based on the resistance rate in that geographic area.

Treatment for Uncomplicated UTIs

UTIs can often be successfully treated with antibiotics prescribed over the phone. In such cases, a health professional provides the people with 3 to 5-day antibiotic regimens without requiring an office urine test. This course is recommended only for women who have typical symptoms of cystitis, who are at low risk for recurrent infection, and who do not have symptoms (such as vaginitis) suggesting other problems. It is always best to have a urine culture done before starting antibiotics when possible.

Antibiotic RegimenOral antibiotic treatment cures nearly all uncomplicated UTIs, although the rate of recurrence remains high. To prescribe the best treatment, the doctor should be made aware of any drug allergies of the person.

The following antibiotics are commonly used for uncomplicated UTIs:

- A recommended regimen is a 3-day course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, commonly called TMP-SMX (Bactrim, Septra, and generic). TMP-SMX combines the antibiotic trimethoprim with a sulfa drug. A single dose of TMP-SMX is sometimes prescribed in mild cases, but cure rates are generally lower than with 3-day regimens. Allergies to sulfa drugs are common and may be serious. Therefore another antibiotic may be prescribed for a patient who is sensitive to sulfa drugs.

- Another first-line option is nitrofurantoin (Furadantin, Macrobid, Macrodantin, and generic). It is usually taken daily for 5 days.

- Fosfomycin (Monurol) is not as effective as other antibiotics but may be used during pregnancy. Resistance rates to this drug are very low.

- Fluoroquinolone antibiotics, also called quinolones, are only recommended for UTIs when other antibiotics cannot be used. Ciprofloxacin (Cipro, generic) is the quinolone antibiotic most commonly prescribed. Quinolones are usually given over a 3-day period. Pregnant women should not take these drugs.

- Other antibiotics may also be used, including amoxicillin-clavulanate cefdinir, cefaclor, and cefpodoxime-proxetil. These drugs may be prescribed when other antibiotics are not appropriate. They are usually given in 3- to 7-day regimens.

After an appropriate course of antibiotic treatment, most people are free of infection. If the symptoms do not clear up within the first few days of therapy, doctors may suggest an alternate course of antibiotics. This may depend on the result of the urine culture. A urine culture may be ordered in order to identify the specific organism causing the condition if not done prior to starting antibiotics.

It should be noted that resistance to many of the commonly used antibiotics is growing and this is why it is now recommended to culture the urine before starting antibiotics. This helps reduce the overuse of these medications.

Treatment for Relapsing InfectionA relapsing infection (caused by treatment failure) occurs within 3 weeks in about 10% of women. Relapse is treated similarly to a first infection, but the antibiotics are usually continued for 7 to 14 days. Relapsing infections may be due to structural abnormalities, abscesses, or other problems that may require surgery. Such conditions should be ruled out.

Treatment for Recurrent Infections

Women who have 2 or more symptomatic UTIs within a 6-month period, or 3 or more episodes over the course of a year, may need preventive antibiotics. All women should use lifestyle measures to prevent recurrences.

Intermittent Self TreatmentMany, if not most, women with recurrent UTIs can effectively self-treat recurrent UTIs without going to a doctor. In general, this requires the following steps:

- As soon as the person develops symptoms, she takes the antibiotic. Infections that occur less than twice a year are usually treated as if they were an initial attack, with single-dose or 3-day antibiotic regimens.

- In some cases, she also performs a clean-catch urine test before starting antibiotics and sends it to the doctor for culturing to confirm the infection.

A woman should consult a doctor under the following circumstances:

- If symptoms have not gone away within 48 hours of starting the antibiotic treatment

- If there is a change in symptoms

- If the person suspects that she is pregnant

- If the person has more than 4 infections a year

Women who are not good candidates for self-treatment are those with impaired immune systems, previous kidney infections, structural abnormalities of the urinary tract, or a history of infection with antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Postcoital AntibioticsIf recurrent infections are clearly related to sexual activity and episodes recur more than two times within a 6-month period, a single preventive dose taken immediately after intercourse is effective. Antibiotics for such cases include TMP-SMX, nitrofurantoin, cephalexin, or a fluoroquinolone (such as ciprofloxacin). Fluoroquinolones are not appropriate during pregnancy.

Continuous Preventive Antibiotics (Prophylaxis)Continuous preventive (prophylactic) antibiotics are an option for some women who do not respond to other measures. With this approach, low-dose antibiotics are taken continuously for 6 months or longer.

Treatment for Kidney Infections (Pyelonephritis)

People with uncomplicated kidney infections (pyelonephritis) may be treated at home with oral antibiotics. Ciprofloxacin (Cipro, generic) or another fluoroquinolone is typically given but other antibiotics, such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), may be used. People with moderate-to-severe acute kidney infection and those with severe symptoms or other complications may need to be hospitalized. In such cases, antibiotics are usually given intravenously for several days. Chronic pyelonephritis may require long-term antibiotic treatment.

Treatments for Specific Populations

Treating Pregnant WomenPregnant women should be screened for UTIs, since they are at high risk for UTIs and their complications. Antibiotics used for treating pregnant women with UTIs include amoxicillin, ampicillin, nitrofurantoin, and cephalosporins (cephalexin). Fosfomycin (Monurol) is not as effective as other antibiotics but is sometimes prescribed for pregnant women. In general, there is no consensus on which antibiotic is best for pregnant women although some types of antibiotics, such as fluoroquinolones and tetracyclines, should not be taken as they can cause harm to the fetus.

Pregnant women with asymptomatic bacteriuria (evidence of infection but no symptoms) have an increased risk for acute pyelonephritis in their second or third trimester. They need screening and treatment for this condition. In such cases, they should be treated with a short course of antibiotics (3 to 5 days). For an uncomplicated UTI, pregnant women may need longer-term antibiotics (7 to 10 days).

Treating Children with UTIsChildren with UTIs are generally treated with TMP-SMX, cephalexin (Keflex, generic) and other cephalosporins, or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (Augmentin, generic). These drugs are usually taken by mouth in either liquid or pill form. Doctors sometimes give them as a shot or IV. Children usually respond to treatment within a few days. Prompt treatment with antibiotics may help prevent renal scarring.

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is a concern for children with UTIs. (See Risk Factors section in this report.) VUR can lead to kidney infection (pyelonephritis), which can cause kidney damage. If the reflux of urine is not severe, the child has a good chance of growing out of this problem without any damage to the kidneys. The two treatment options for children with VUR that is more severe or has caused infections are long-term antibiotics to prevent infections or surgery to correct the condition. However, there is debate as to the benefit of these approaches. Current guidelines advise that antibiotics do not really help prevent recurrent UTIs in children, and that VUR itself may not substantially increase the risk for recurrent UTI.Children with acute kidney infection are treated with various antibiotics including oral cefixime (Suprax) or a short course (2 to 4 days) of an intravenous (IV) antibiotic (typically gentamicin, given in one daily dose). An oral antibiotic then follows the IV.

Management of Catheter-Induced Urinary Tract Infections

Catheter-induced UTIs are very common, and preventive measures are extremely important. In-dwelling catheters should not be used unless absolutely necessary and they should be removed as soon as possible. Long-term catheter use is associated with increased risk for infections. For men, external catheters (condom catheters) may be an alternative to indwelling catheters.

Daily Catheter HygieneA typical catheter comes pre-connected and sealed and uses a drainage bag system. To prevent infection, some of the following tips may be helpful:

- Drink plenty of fluids.

- Make sure the catheter tube is free of any knots or kinks.

- Clean the catheter and the area around the urethra with soap and water daily and after each bowel movement. (Women should be sure to clean front to back.)

- Wash hands before touching the catheter or surrounding area.

- Never disconnect the catheter from the drainage bag without careful instructions from a health professional on strict methods for preventing infection.

- Keep the drainage bag off the floor.

- Stabilize the bag against the leg using a leg strap, tape or some other system.

People using catheters who develop UTIs with symptoms should be treated for each episode with antibiotics and the catheter should be removed, if possible, or changed. A major problem in treating catheter-related UTIs is that the organisms involved are constantly changing. Because there are likely to be multiple species of bacteria, doctors generally recommend an antibiotic that is effective against a wide variety of microorganisms.

Although high bacteria counts in the urine (bacteriuria) occur in most catheterized people, administering antibiotics to prevent a UTI is rarely recommended. Many catheterized people do not develop symptomatic UTIs even with high bacteria counts. If bacteriuria occurs without symptoms, antibiotic therapy has little benefit if the catheter is to remain in place for a long period.

Catheterization is accomplished by inserting a catheter (a hollow tube, often with an inflatable balloon tip) into the urinary bladder. This procedure is performed for urinary obstruction, non-functioning bladder due to many different causes, following surgical procedures to the urethra, in unconscious people (due to surgical anesthesia or coma), or for any other problem in which the bladder needs to be kept empty (decompressed) and urinary flow ensured.

Medications

Although antibiotics are the first treatment choice for UTIs, antibiotic-resistant strains of E. coli, the most common cause of UTIs, are increasing worldwide. As more bacteria have become resistant to the standard UTI treatment TMP-SMX, the antibiotics nitrofurantoin and fosfomycin have become alternative first-line choices for drug therapy.

Below are some of the antibiotic classes used most commonly to treat UTIs.

Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX)

The typical treatment for an uncomplicated UTI is a 3-day course of the combination drug trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, commonly called TMP-SMX (Bactrim, Septra, and generic). A 1-day course is somewhat less effective but poses a lower risk for side effects. Longer courses (7 to 10 days) work no better than the 3-day course and have a higher rate of side effects.

TMP-SMX should not be used during the first trimester in pregnant women and should not be used in people who are allergic to sulfa drugs. Allergic reactions can be very serious. Trimethoprim (Proloprim or Trimpex) is sometimes used alone in those allergic to sulfa drugs. TMP-SMX can interfere with the effectiveness of oral contraceptives. High rates of bacterial resistance to TMP-SMX exist in many parts of the United States.

Nitrofurantoin

Nitrofurantoin (Furadantin, Macrodantin, Macrobid, and generic) is an antibiotic that is used specifically for UTIs as an alternative to TMP-SMX. It is usually taken twice a day for 5 days. It is not useful for treating kidney infections. Nitrofurantoin frequently causes stomach upset and interacts with many drugs. Other chronic or serious medical conditions may also affect its use. It can be used during pregnancy but should not be used in pregnant women within 1 to 2 weeks of delivery, in nursing mothers, or in those with kidney disease.

Fosfomycin

The antibiotic fosfomycin (Monurol) may be prescribed as a 1-dose treatment for women who are pregnant or for other select people. In general, it is less effective for treating UTIs than TMP-SMX or nitrofurantoin.

Beta-Lactams

Beta-lactam antibiotics share common chemical features and include penicillin, cephalosporins, and some newer drugs.

PenicillinUntil recent years, the standard treatment for a UTI was 10 days of amoxicillin, a penicillin antibiotic, but due to antibiotic resistance it is now ineffective against E. coli bacteria in many cases. A combination of amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin) is sometimes given for drug-resistant infections.

CephalosporinsAntibiotics known as cephalosporins are alternatives for infections that do not respond to standard treatments or for special populations. They are often classed as first, second, or third generation. Cephalosporins used for treatment of UTIs include cephalexin (Keflex, generic), cefadroxil (Duricef, generic), cefuroxime (Ceftin, generic), loracarbef (Lorabid), and cefixime (Suprax), among others.

Cefiderocol (Fetroja) is a newly approved cephalosporin for complicated UTIs or kidney infections to be used when other antibiotics have failed. Cefiderocol is indicated for the treatment of multi-drug resistant Gram-negative bacteria.

Other Beta-Lactam DrugsOther beta-lactam antibiotics have been developed. For example, pivmecillinam (a form of mecillinam), is commonly used in Europe for UTIs. It is not available in the United States.

Fluoroquinolones (Quinolones)

Fluoroquinolones (also simply called quinolones) were formerly used as alternatives to TMP-SMX but they are now recommended for UTIs only when other antibiotics are not appropriate. Fluoroquinolones are effective for treating acute kidney infections (pyelonephritis). Examples of quinolones include ofloxacin (Floxacin, generic), ciprofloxacin (Cipro, generic), and levofloxacin (Levaquin, generic). These drugs can have severe side effects that the person should discuss with the doctor.

Pregnant women should not take fluoroquinolone antibiotics. They also have more adverse effects in children than other antibiotics and should not be the first-line option in most pediatric situations.

Other Antibiotics Used for UTIs

DoripenemDoripenem (Doribax) is a newer carbapenem antibiotic, which is used to treat complicated UTIs and pyelonephritis. It is given by injection.

Vabomere (meropenem and vaborbactam)Vabomere, a combination of a beta-lactam antibiotic (meropenem) and a penicillinase inhibitor (vaborbactam), has been approved by the FDA in 2017 for the treatment of complicated UTIs, including pyelonephritis caused by E coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterobacter cloacae. This drug is also given by injection.

TetracyclinesTetracyclines include doxycycline, tetracycline, and minocycline. They may be used for UTIs caused by Mycoplasma or Chlamydia. Side effects include skin reactions to sunlight (photosensitivity) and permanent tooth discoloration. Tetracyclines cannot be taken by children or pregnant women.

AminoglycosidesAminoglycosides include gentamicin, tobramycin, and amikacin. They are given by injection for very serious bacterial infections. They can be given only in combination with other antibiotics. Gentamicin is the most commonly used aminoglycoside for severe UTIs. They can have very serious side effects, including damage to hearing, sense of balance, and kidneys.

Medications for Treating Symptoms

Although antibiotics can cure most UTIs, severe symptoms can persist for several days until the drug eliminates the bacteria. Other medications may be used for relieving symptoms until the antibiotics take action.

PhenazopyridinePhenazopyridine (Pyridium, Uristat, AZO Standard, Urodol, and generic) relieves pain and burning caused by the infection. People should not take this medicine for more than 2 days without discussing it with their doctor.

Side effects include headache and upset stomach. The drug turns urine a red or orange color, which can stain fabric and be difficult to remove. Rarely, it can cause serious side effects, including shortness of breath, a bluish skin, a sudden reduction in urine output, and confusion. In such cases, people should immediately call the doctor.

Antispasm DrugsMethenamine (Hiprex, Urised, Cystex, and generic) or flavoxate (Urispas, generic) reduce bladder spasms, which may occur with some UTIs. However, these drugs can have severe side effects, which the person should discuss with the doctor.

Lifestyle Changes

Although there is no evidence that good hygiene makes a real difference in preventing UTIs, it is always a wise practice. The following are some hygiene tips for women:

- Wipe front-to-back after urinating.

- Wash the genital and urinary areas from front to back with liquid soap and water after each bowel movement.

- Change underwear at least once a day. (Mild detergents are best for washing underwear.)

- Take showers rather than baths.

- Avoid bath oils, feminine hygiene sprays, douches, and powders. As a general rule, do not use any product containing perfumes or other possible allergens near the genital area. Douching is never recommended as it may irritate the vagina and urethra and increase the risk of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).

- Tampons or sanitary napkins should be changed frequently.

- Drink plenty of fluids and urinate frequently.

Appropriate hygiene and cleanliness of the genital area may help reduce the chances of introducing bacteria through the urethra. Females are especially vulnerable to this, because the urethra is in close proximity to the rectum. The genitals should be cleaned and wiped from front to back to reduce the chance of dragging E. coli from the rectal area to the urethra.

Sexual Precautions

Sexual intercourse is one of the most common risk factors for uncomplicated UTIs in women. In addition to abstaining from sex while you have a UTI, the following recommendations may reduce the risks from sexual activity:

- Keep the genital and anal areas clean before and after sex. Urinate before and after intercourse to empty the bladder and cleanse the urethra of bacteria.

- Discuss with your doctor contraceptive alternatives to the spermicides used with condoms and diaphragms.

- Avoid sex with multiple partners. This can cause many health problems, including STDs.

Cranberries, Blueberries, and Lingonberries

Cranberries, blueberries, and lingonberries (European relative of the cranberry), are three fruits thought by many to have protective properties against urinary tract infections. These fruits contain compounds called tannins (or proanthocyanadins). Tannins may prevent E. coli from adhering to cells in the urinary tract, thereby inhibiting infection.

Cranberry juice is the best-studied home remedy for UTIs. Many small studies have indicated that cranberry juice may help decrease the number of symptomatic UTIs, especially for women with recurrent urinary tract infections. However, randomized controlled studies and reviews suggest that cranberries provide little benefit. Using concentrated cranberry tablets may be more effective than cranberry juice.

Fluid Intake

Studies indicate that higher water intake (over 1.5 L or 50 oz each day) lowers the risk for urinary tract infections in both adults and children. This is probably because with more frequent urination, bacteria don't have enough time to attach themselves to the lining of the bladder.

Probiotics and Lactobacilli

Probiotics are beneficial microorganisms that may protect against infections in the genital and urinary tracts. The best-known probiotics are the lactobacilli strains, such as Lactobacillus acidophilus, which is found in yogurt and other fermented milk products (kefir), as well as in dietary supplement capsules. The probiotics bifidobacteria and GG lactobacilli may also be helpful. Studies do not conclusively show a benefit for probiotics in preventing UTIs. More research is needed.

Resources

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases -- www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/kidney-disease

- Urology Care Foundation -- www.urologyhealth.org

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists -- www.acog.org

References

Abraham SN, Miao Y. The nature of immune responses to urinary tract infections. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(10):655-663. PMID: 26388331 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26388331.

American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Male circumcision. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):e756-e785. PMID: 22926175 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22926175.

Anger J, Lee U, Ackerman AL, et al. Recurrent Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections in Women: AUA/CUA/SUFU Guideline. J Urol. 2019;202(2):282-289. PMID: 31042112 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31042112.

Cooper KL, Badalato GM, Rutman MP. Schaeffer AJ, Matulewicz RS, Klumpp DJ. Infections of the urinary tract. In: Partin AW, Dmochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 55.

Cortes-Penfield NW, Trautner BW, Jump RLP. Urinary Tract Infection and Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Older Adults. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017;31(4):673-688. PMID: 29079155 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29079155.

Elder JS. Vesicoureteral reflux. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 554.

Fasugba O, Mitchell BG, McInnes E, et al. Increased fluid intake for the prevention of urinary tract infection in adults and children in all settings: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect. 2020;104(1):68-77. PMID: 31449918 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31449918.

Gupta K, Grigoryan L, Trautner B. Urinary tract infection. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(7):ITC49-ITC64. PMID: 28973215 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28973215.

Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(5):e103-120. PMID: 21292654 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21292654.

Jerardi KE, Jackson EC. Urinary tract infections. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 553.

Kang CI, Kim J, Park DW, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Antibiotic Treatment of Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infections. Infect Chemother. 2018;50(1):67-100. PMID: 29637759 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29637759.

Keren R, Shaikh N, Pohl H, et al. Risk factors for recurrent urinary tract infection and renal scarring. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):e13-21. PMID: 26055855 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26055855.

Mody L, Juthani-Mehta M. Urinary tract infections in older women: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311(8):844-854. PMID: 24570248 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24570248.

Okarska-Napierala M, Wasilewska A, Kuchar E. Urinary tract infection in children: Diagnosis, treatment, imaging - Comparison of current guidelines. J Pediatr Urol. 2017; 13(6):567-573. PMID: 28986090 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28986090.

Sobel JD, Brown P. Urinary tract infections. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 72.

Stein R, Dogan HS, Hoebeke P, et al; European Association of Urology; European Society for Pediatric Urology. Urinary tract infections in children: EAU/ESPU guidelines. Eur Urol. 2015;67(3):546-58. PMID: 25477258 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25477258.

Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infection, Roberts KB, Downs SM, et al. Reaffirmation of AAP Clinical Practice Guideline: The diagnosis and management of the initial urinary tract infection in febrile infants and young children 2-24 months of age. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6). pii: e20163026. PMID: 27940735 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27940735.

Trautner BW, Hooton TM. Health care-associated urinary tract infections. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 302.

Vigil HR, Hickling DR. Urinary tract infection in the neurogenic bladder. Transl Androl Urol. 2016;5(1):72-87. PMID: 26904414 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26904414.

Review Date: 2/27/2020

Reviewed By: Sovrin M. Shah, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.