Hypothyroidism - InDepth

Autoimmune thyroiditis - InDepth; Hashimoto's thyroiditis - InDepth; Myxedema - InDepth; Adult hypothyroidism - InDepth; Underactive thyroid - InDepth; Goiter - hypothyroidism - InDepth; Thyroiditis - hypothyroidism - InDepth; Thyroid hormone - hypothyroidism - InDepthAn in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of hypothyroidism.

Highlights

What is Hypothyroidism?

Hypothyroidism, also called underactive thyroid, is a condition in which the thyroid gland does not produce enough hormones. Hypothyroidism can be caused by the autoimmune disorder Hashimoto thyroiditis, irradiation or surgical removal of the thyroid gland, and medications that reduce thyroid hormone levels.

Anyone can develop hypothyroidism, but people ages 50 years and above are at greater risk, and women are at higher risk than men. Only a small percentage of people have full-blown (overt) hypothyroidism. The prevalence of overt hypothyroidism in the general population varies between 0.3% and 3.7% in the United States. Many more people have mildly underactive thyroid glands (subclinical hypothyroidism).

Symptoms

Symptoms of hypothyroidism include:

- Dry skin

- Thin, brittle hair and fingernails

- Increased sensitivity to cold

- Feeling tired

- Slow thinking

- Constipation

- Depression

- Muscle and joint pain

- Heavier menstrual periods

- Hoarse voice

- Weight gain or difficulty losing weight

- Fertility problems

In older patients symptoms can be only fatigue, weakness, memory loss, or chest pain.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Hypothyroidism can cause serious complications if left untreated. Fortunately, it can be easily diagnosed with blood tests that measure levels of the pituitary thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and the thyroid hormone thyroxine (T4). Your health care provider may also want to test for antithyroid antibodies and check your cholesterol levels. Based on these test results, the provider will decide whether to prescribe medication or simply see you again in 6 to 12 months to review your symptoms with you again, if necessary.

Medications

The standard drug treatment for hypothyroidism is a daily dose of a synthetic thyroid hormone called levothyroxine. This drug helps normalize blood levels of thyroid hormones, T4, and triiodothyronine (T3). Continuous treatment with an adequate dose of levothyroxine will also normalize TSH levels.

Many prescription medications and dietary supplements can interact with levothyroxine and either increase or decrease its potency. (Make sure your provider knows all the medications and supplements you are taking.) Large amounts of dietary fiber can also interfere with levothyroxine treatment. People who eat high-fiber diets may need higher doses of the drug. Not taking the medication as instructed (on an empty stomach at least 2 hours after or 1 hour before eating) is the most common cause of poor absorption of the medication.

Introduction

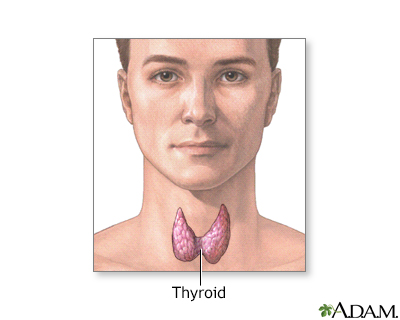

Hypothyroidism is a condition in which the thyroid gland does not make enough thyroid hormones. Hypothyroidism is often called underactive or low thyroid.

The thyroid is a small, butterfly-shaped gland located in the front of the neck. The thyroid gland produces hormones, notably thyroxine (T4, 80%) and triiodothyronine (T3, 20%), which stimulate vital processes in every part of the body. These thyroid hormones have a major impact on the following functions:

- Growth

- Use of energy and oxygen

- Heat production

- Fertility

- Metabolism of vitamins, proteins, carbohydrates, fats, electrolytes, and water

- Immune regulation in the intestine

Thyroid hormones can also alter the actions of other hormones and drugs.

The thyroid gland, a part of the endocrine (hormone) system, plays a major role in regulating the body's metabolism.

Iodine and Thyroid Hormone Production

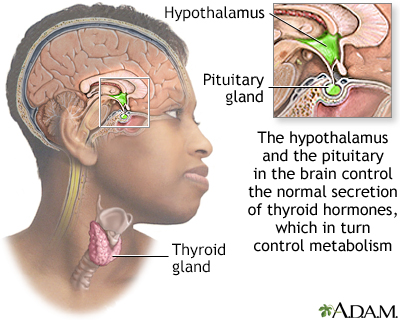

The regulation of thyroid function is a complex process. It involves 4 hormones and iodine.

IodineIodine is a key element used by the thyroid gland to make the hormone thyroxine (T4). Eighty percent of the body's iodine supply is stored in the thyroid.

Thyroid HormonesFour hormones are critical in the regulation of thyroid function:

-

Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH).

TRH is produced in a region of the brain called the hypothalamus, which monitors and regulates thyrotropin (TSH) levels. -

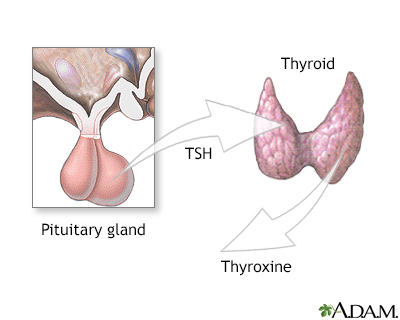

Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).

TSH, also called thyrotropin, is secreted by the pituitary gland. TSH directly affects the process of iodine trapping and thyroid hormone production. When thyroxine (T4) levels drop even slightly, the pituitary gland goes into action to pump up secretion of TSH so that it can stimulate T4 production. When T4 levels fall, TSH levels increase. -

Thyroxine (T4).

T4 is the key hormone produced in the thyroid gland. Low levels of T4 producehypothyroidism

, and high levels producehyperthyroidism

. -

Triiodothyronine (T3).

Thyroxine (T4) converts to triiodothyronine (T3), which is a more biologically active hormone. Only about 20% of T3 is actually formed in the thyroid gland. The rest is synthesized from circulating T4 in tissues outside the thyroid, such as the liver and kidney. Once T4 and T3 are in the circulation, they typically bind to substances called thyroid hormone transport proteins (thyroid binding globulins). After having their effect in various parts of the body, the thyroid hormones are later inactivated and the iodine is recycled to form new thyroxine.

Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism occurs when thyroxine (T4) levels drop so low that body processes begin to slow down. Hypothyroidism was first diagnosed in the late 19th century, when doctors observed that surgical removal of the thyroid gland resulted in swelling of the hands, face, feet, and the tissues around the eyes. They named this syndrome myxedema and correctly concluded that it was due to the absence of thyroid hormones, which are normally produced by the thyroid gland. Hypothyroidism is usually progressive and irreversible. Treatment, however, is nearly always completely successful and allows a person to live a fully normal life.Hypothyroidism is classified as either overt or subclinical disease. That diagnosis is determined on the basis of the TSH laboratory blood tests:- Levels from 0.45 to 4.5 mU/L are considered normal. (TSH results can vary by laboratory with normal as low as 0.3 mU/L or as high as 5.5 mU/L.)

- Levels from 4.5 to 10 mU/L indicate mildly underactive thyroid (subclinical hypothyroidism).

- Levels greater than 10 mU/L indicate overt hypothyroidism, which should be treated with medication.

Subclinical hypothyroidism (mildly underactive thyroid) is a condition in which TSH levels have started to increase in response to an early decline in T4 levels in the thyroid. However, blood tests for T4 are still normal. The person may have mild symptoms (usually slight fatigue) or none at all. Mildly underactive thyroid is very common and is a topic of considerable debate among health care providers because it is not clear how to manage this condition.

In many people, subclinical hypothyroidism eventually progresses to the full-blown disorder.

Other factors associated with a higher risk of developing clinical overt hypothyroidism include:

- Being an older woman (5% to 10% of women over age 50 have subclinical hypothyroidism and 2% women between age 70 and 80 years have overt hypothyroidism)

- Having a goiter (enlarged thyroid gland)

- Having high levels of thyroid antibodies

- Having immune factors that suggest an autoimmune condition

- Having family members (mother, sister, aunt) who have thyroid disease

Causes

Many permanent or temporary conditions can reduce thyroid hormone secretion and cause hypothyroidism. More than 90% of hypothyroidism cases occur from problems that start in the thyroid gland. In such cases, the disorder is called primary hypothyroidism. (Secondary hypothyroidism is caused by disorders of the pituitary gland. Tertiary hypothyroidism is caused by disorders of the hypothalamus.)The two most common causes of primary hypothyroidism are:

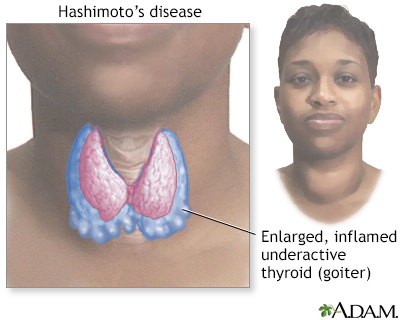

Hashimoto thyroiditis.

This is an autoimmune condition (chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis) in which the body's immune system attacks its own thyroid cells.- Overtreatment of

hyperthyroidism

(an overactive thyroid).

Autoimmune Diseases of the Thyroid

Hashimoto thyroiditis, atrophic thyroiditis, and postpartum thyroiditis are all autoimmune diseases of the thyroid. An autoimmune disease occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks the body's own healthy cells. In the case of autoimmune thyroiditis, a common form of primary hypothyroid disease, the cells under attack are in the thyroid gland and include, in particular, a thyroid protein called thyroid peroxidase. The autoimmune disease process results in the destruction of thyroid cells.

Hashimoto ThyroiditisThe most common form of hypothyroidism is Hashimoto thyroiditis, a genetic disease named after the Japanese doctor who first described thyroid inflammation (swelling of the thyroid gland). Women are more likely than men to develop this disease.

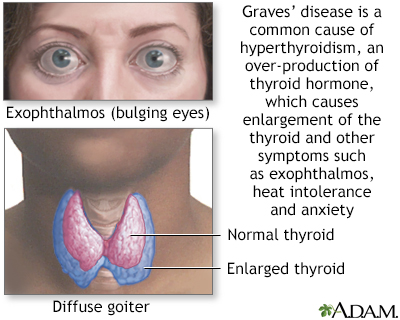

An enlargement of the thyroid gland, called a goiter, is almost always present and may appear as a growth in the neck. Hashimoto thyroiditis is permanent and requires lifelong treatment. Both genetic and environmental factors appear to play a role in its development.The other main type of autoimmune thyroid disease is Graves disease, which causes hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid).

Atrophic Thyroiditis

Atrophic thyroiditis is similar to Hashimoto thyroiditis, except a goiter is not present.

Riedel ThyroiditisRiedel thyroiditis is a rare autoimmune disorder, in which scar tissue progresses in the thyroid until it produces a hard, stony mass that suggests cancer. Hypothyroidism develops as the scar tissue replaces healthy tissue. Surgery is usually required, although early stages may be treated with corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive drugs.

Autoimmune Thyroiditis Due to PregnancyHypothyroidism may also occur in women who develop antibodies to their own thyroid during pregnancy, causing inflammation of the thyroid after delivery.

Subacute Thyroiditis

Subacute thyroiditis is a temporary condition that passes through 3 phases: hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and a return to normal thyroid levels.

People may have symptoms of both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism (such as rapid heartbeat, nervousness, and weight loss, along with or followed by depression and fatigue), and they can feel extremely sick. Symptoms last about 6 to 8 weeks and then usually resolve, although each form carries some risk for becoming chronic.

The 3 forms of subacute thyroiditis follow a similar course.

Painless Postpartum Subacute ThyroiditisPostpartum thyroiditis is an autoimmune condition that occurs in up to 10% of pregnant women and tends to develop between 4 to 12 months after delivery. In most cases, the woman develops a small, painless goiter. This condition is generally self-limiting and requires no therapy unless the hypothyroid phase is prolonged. If so, therapy may be thyroxine replacement for a few months. A beta-blocker drug may also be recommended if the hyperthyroid phase needs treatment. About 20% of women with this condition go on to develop permanent hypothyroidism.

Painless Sporadic, or Silent ThyroiditisThis painless condition is very similar to postpartum thyroiditis, except it can occur in both men and women and at any age. About 20% of people with silent thyroiditis may develop chronic hypothyroidism. Treatment considerations are the same as for postpartum subacute thyroiditis. Some medications may cause this type of thyroiditis.

Painful, or Granulomatous ThyroiditisSubacute granulomatous thyroiditis, also called de Quervain thyroiditis, comes on suddenly with mild to severe neck pain and swelling, and often occurs several weeks after flu-like symptoms. It is thought to be caused by a viral infection and generally occurs in the summer. It is much more common in women than men and is usually a temporary condition. Treatments typically include pain relievers and, in severe cases, corticosteroids or beta-blockers.

After Treatment of Hyperthyroidism

Many people who receive radioactive iodine treatments for an overactive thyroid develop permanent hypothyroidism within a year of therapy. Radioactive iodine is a common treatment for Graves disease, which is the most common form of hyperthyroidism, an autoimmune condition resulting in excessive secretion of thyroid hormones.After treatment for Graves disease, many people gradually develop hypothyroidism and need to take thyroid hormones for the rest of their lives. Other types of treatment for overactive thyroid glands (such as anti-thyroid drugs or surgery) may also result in hypothyroidism.

Iodine Abnormalities

Too much or too little iodine can cause hypothyroidism. If there is a deficiency of iodine, the body cannot manufacture thyroxine (T4). Millions of people around the world have hypothyroidism because of insufficient iodine in their diets. This global public health issue used to be even more widespread, but has now been almost completely resolved due to salt iodization programs. Too much iodine is a signal to inhibit the conversion process of T4 to T3. The end result in both cases is inadequate production of thyroid hormones. Some evidence suggests that excess iodine may trigger the process leading to Hashimoto thyroiditis.

Thyroid Surgery

People who have complete removal (total thyroidectomy) of the thyroid gland to treat thyroid cancer need lifetime treatment with thyroid hormone. Removing one of the two lobes of the thyroid gland (hemithyroidectomy), usually because of benign growths on the thyroid gland, rarely produces hypothyroidism. The remaining thyroid lobe will generally grow so that it can produce sufficient amounts of thyroid hormone for normal function. However, to prevent the formation of additional nodules, many doctors recommend thyroid hormone treatment.

People with Graves disease who have surgery to remove most of both thyroid lobes (subtotal thyroidectomy) may develop hypothyroidism.

Drugs and Medical Treatments that Reduce Thyroid Levels

LithiumA drug used to treat bipolar disorder, has multiple effects on thyroid hormone synthesis and secretion. Many people treated with lithium go on to develop hypothyroidism and some develop a goiter. Most people develop subclinical hypothyroidism, but a small percentage experience overt hypothyroidism.

Amiodarone (Cordarone)Is used to treat abnormal heart rhythms, contains high levels of iodine and can induce hyper- or hypothyroidism, particularly in people with existing thyroid problems.

Other DrugsDrugs used for treating epilepsy, such as phenytoin and carbamazepine, can reduce thyroid hormone levels. Interferons and interleukins, which are used to treat hepatitis, multiple sclerosis, and other conditions, can induce either hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. Some drugs used in cancer chemotherapy, such as sunitinib (Sutent) or imatinib (Gleevec), can also cause or worsen hypothyroidism.

Radiation TherapyHigh-dose radiation for cancers of the head or neck and for Hodgkin disease can cause hypothyroidism up to 10 years after treatment.

Other Medical Conditions

Several medical conditions involve the thyroid and can change the normal gland tissue so that it no longer produces enough thyroid hormone. Examples include hemochromatosis, scleroderma, and amyloidosis.

Causes of Secondary and Tertiary Hypothyroidism

In rare instances, usually due to a tumor, the pituitary gland will fail to produce TSH, the hormone that stimulates the thyroid to produce its hormones. In such cases, the thyroid gland shrinks and secondary hypothyroidism occurs.

Causes of Hypothyroidism in Infants

Hypothyroidism in newborns (known as congenital hypothyroidism) occurs in one in every 3,000 to 4,000 births. It usually persists throughout life.Permanent Congenital HypothyroidismIn most cases of permanent congenital hypothyroidism, the thyroid gland is missing, underdeveloped, or not properly located. In other cases, hormone production is impaired or the pituitary or hypothalamus glands function abnormally. Genetic abnormalities may be a factor in congenital hypothyroidism, but in many cases the cause is unknown.

Temporary Hypothyroidism in InfantsTemporary hypothyroidism can also occur in infants. Possible causes include various immunologic, environmental, and genetic factors, including the following:

- Women who have an underactive (low) thyroid, including those who develop the problem during pregnancy, are at increased risk for delivering babies with congenital (newborn) hypothyroidism. Maternal hypothyroidism can also cause premature delivery and low birth weight.

- Some of the drugs used to treat hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid) block the production of thyroid hormone. These same drugs can also cross the placenta and cause hypothyroidism in the infant.

- If a pregnant woman has untreated hyperthyroidism, her newborn infant may have hypothyroidism for a short period of time. This is because the excess thyroid hormone in the woman's blood crosses the placenta and signals the fetus not to produce as much of its own thyroid hormone.

- Iodine deficiency may cause temporary hypothyroidism. (Exposure to too much iodine immediately after birth, for example from iodine-containing disinfectants or medicines, can also cause thyroid dysfunction.)

- Premature birth increases the risk of temporary hypothyroidism in the infant.

Children with temporary congenital hypothyroidism should be followed up regularly during adolescence and adulthood for possible thyroid problems. The risk for future thyroid problems is highest when girls born with this condition reach adulthood and become pregnant.

Risk Factors

Many people have some degree of thyroid disease, mostly subclinical hypothyroidism (mildly underactive thyroid). Only a small percentage of people have full-blown (overt) clinical hypothyroidism.

Gender

Women are much more likely than men to develop hypothyroidism. While hypothyroidism most often occurs in middle-aged and older women, it is also common during pregnancy.

Pregnancy affects the thyroid in a number of ways. The thyroid gland may increase in size, and changes in reproductive hormones and thyroid hormone transport proteins can cause changes in thyroid hormone levels. Pregnancy also boosts iodine requirements in both the mother and fetus. In addition, some women develop antibodies to their own thyroid during pregnancy, which causes postpartum subacute thyroiditis and can increase the risk of developing permanent hypothyroidism.

Age

The risk for hypothyroidism is greater after age 50 years and increases with age. Symptoms may overlap with and be similar to those of menopause. However, hypothyroidism can affect people of all ages.

Family History

Genetics plays a role in many cases of underactive and overactive thyroid. Many people with hypothyroidism have a family history of thyroid problems, particularly Hashimoto thyroiditis.

Lifestyle Factors

Smoking affects thyroid function and significantly increases risk for thyroid disease, especially autoimmune Hashimoto thyroiditis and postpartum thyroiditis. Smoking also increases hypothyroidism's negative effects on the arteries and heart.

Medical Conditions Associated with Hypothyroidism

People with certain medical conditions have a higher risk for hypothyroidism. These conditions include:

- Autoimmune disorders such as type 1 diabetes, systemic lupus erythematosus, pernicious anemia, rheumatoid arthritis, celiac disease, Addison disease (primary adrenal insufficiency), and myasthenia gravis.

- Chromosomal disorders such as Down syndrome and Turner syndrome.

- Eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa.

Symptoms

Symptoms of hypothyroidism tend to develop slowly over a long period of time and vary widely from person to person. Intermittent symptoms that vary from hour to hour or day to day are rarely due to thyroid hormone problems.

Early SymptomsCommon early symptoms of hypothyroidism may include:

- Dry, pale skin

- Thin, brittle hair and fingernails

- Increased sensitivity to cold

- Feeling tired

- Constipation

- Slow thinking

- Depression

- Muscle and joint pain

- Slow heart rate

- Heavier menstrual periods

- Hoarse voice

- Enlarged tongue

- Weight gain or difficulty losing weight

- Fertility problems

Symptoms of severe, untreated hypothyroidism may include:

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- Puffy "moon" face

- Cognitive problems, including slow speech and difficulty concentrating

- Numbness in fingers and toes (peripheral neuropathy)

- Hair loss

- Decreased sense of taste and smell

- Sleep apnea

- Milky discharge from breasts (galactorrhea)

- Accumulation of fluid in the skin and tissues (myxedema)

- Decreased heart function

Symptoms in Infants and Children

In the United States, nearly all babies are screened for hypothyroidism in order to prevent cognitive developmental problems that can occur if treatment is delayed. Symptoms of hypothyroidism in children vary depending on when the problem first develops.

- Most children who are born with a defect that causes congenital hypothyroidism initially have no obvious symptoms. Symptoms that sometimes appear in newborns may include jaundice (yellowish skin), noisy breathing, and an enlarged tongue.

- Early symptoms of undetected and untreated hypothyroidism in infants include feeding problems, failure to thrive, constipation, hoarseness, and sleepiness.

- Later symptoms in untreated children include protruding abdomen; rough, dry skin; and delayed teething. In advanced cases, yellow raised bumps (called xanthomas) may appear under the skin, the result of cholesterol buildup.

- If children with hypothyroidism do not receive proper treatment in time, they may be extremely short for their age; have a puffy, bloated appearance; and have intellectual disabilities. Any child whose growth is abnormally slow should be examined for hypothyroidism.

Complications

Hypothyroidism increases the risk for physical and mental problems.

Emergency Conditions

Myxedema ComaA rare, life-threatening complication of untreated hypothyroidism. Symptoms include:

- Constipation

- Delirium

- Fluid buildup

- Reduced lung function

- Seizures

- Severe drop in body temperature (hypothermia)

- Slow heart rate

- Stupor

- Urine retention

- Coma

Myxedema coma is uncommon, but it may develop in untreated people who are under severe stress, such as those with an infection or severe cold, or after surgery. Certain drugs (such as sedatives, painkillers, narcotics, amiodarone, and lithium) may increase the risk. Emergency treatment is required.

Suppurative ThyroiditisA life-threatening infection of the thyroid gland. It is very rare, since the thyroid is normally resistant to infection. People with pre-existing thyroid diseases, such as Hashimoto thyroiditis may be at higher than average risk for suppurative thyroiditis. It often begins with an upper respiratory infection. Symptoms include:

- Difficulty swallowing and speaking

- Fever

- Neck pain

- Rash

Immediate treatment is required.

Heart Problems

Thyroid hormones, particularly triiodothyronine (T3), affect the heart directly and indirectly. They are closely linked with heart rate and heart output. T3 provides particular benefits by relaxing the smooth muscles of blood vessels. This helps keep the blood vessels open so that blood flows smoothly through them.

Hypothyroidism is associated with:

Unhealthy cholesterol levels.

Hypothyroidism raises levels of total cholesterol, LDL (bad) cholesterol, triglycerides, and other lipids associated with heart disease. Treating the thyroid condition with thyroid replacement therapy can significantly reduce these levels.High blood pressure.

Hypothyroidism can slow the heart rate, reduce the heart's pumping capacity, and increase the stiffness of blood vessel walls. These effects can lead to high blood pressure. Everyone with chronic hypothyroidism, especially pregnant women, should have their blood pressure checked regularly.Heart failure.

Hypothyroidism can affect the heart muscle's contraction and increase the risk of heart failure in people with heart disease.Pericardial effusion.

Hypothyroidism sometimes leads to the buildup of fluid in the sac that surrounds the heart, known as a pericardial effusion.

The evidence for effects of subclinical hypothyroidism on heart disease is mixed. Some studies, but not all, indicate that subclinical hypothyroidism increases the risks for coronary artery disease, heart failure, and even stroke. However, many researchers believe that treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism will not help prevent or improve these problems.

Mental Health Effects

DepressionCommon in hypothyroidism and can be severe. Hypothyroidism should be considered as a possible cause of any chronic depression, particularly in older women.

Mental and Behavioral ImpairmentUntreated hypothyroidism can, over time, cause mental and behavioral impairment and, eventually, even dementia (memory loss). Whether treatment can completely reverse problems in memory and concentration is uncertain, although research suggests that only mental impairment in hypothyroidism that occurs at birth is permanent.

Other Health Effects of Hypothyroidism

The following medical conditions have also been associated with hypothyroidism. Often the causal relationship is not clear in individual cases. These conditions include:

- Iron deficiency anemia.

- Respiratory problems.

- Abnormal kidney function.

- Glaucoma.

- Headache (hypothyroidism may worsen headaches in people predisposed to them).

- Thyroid cancer (people with Hashimoto thyroiditis and people who received childhood radiation treatments to the head or neck are at higher risk for this rare form of cancer).

Infertility and Pregnancy

Hypothyroidism can interfere with fertility and increase the risk for miscarriage and preterm births. Many women with overt hypothyroidism have menstrual cycle abnormalities and some fail to ovulate. In women who do become pregnant, overt hypothyroidism can affect normal fetal development.

Women who have a history of miscarriages often have antithyroid antibodies during early pregnancy and are at risk for developing autoimmune thyroiditis over time. Postpartum thyroiditis is a specific type of autoimmune thyroiditis that develops within the first year following delivery. It can cause overactive thyroid (thyrotoxicosis), followed by underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism).

Effects of Hypothyroidism on Infants and Children

Children of Untreated MothersChildren born to untreated pregnant women with hypothyroidism are at risk for impaired mental performance, including attention problems and verbal impairment.

Effects of Hypothyroidism During InfancyTransient hypothyroidism is common among premature infants. Although temporary, severe cases can cause difficulties in neurologic and mental development.

Infants born with permanent congenital (inborn) hypothyroidism need to receive treatment as soon as possible after birth to prevent intellectual disability, stunted growth, and other aspects of abnormal development (a syndrome referred to as cretinism). An early start of lifelong treatment avoids or minimizes this damage. Even with early treatment, mild problems in memory, attention, and mental processing may persist into adolescence and adulthood.

Effects of Childhood-Onset HypothyroidismIf hypothyroidism develops in children older than 2 years, severe intellectual disability is not a danger, but physical growth may be slowed and tooth eruption delayed. If treatment is delayed, adult height could be affected. Even with treatment, some children with severe hypothyroidism may have attention problems and hyperactivity.

Diagnosis

A health care provider will diagnose hypothyroidism after completing a medical history and physical exam, and performing laboratory tests on the person's blood. The standard test for diagnosing hypothyroidism is to measure blood levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH). Based on the results of the TSH test, your provider may order additional thyroid tests.

Physical Examination

The provider will check your neck for signs of an enlarged thyroid (goiter), which may be a sign of Hashimoto thyroiditis. The provider will also check your heart, eyes, hair, skin, and reflexes for signs of hypothyroidism.

Blood Tests

Blood tests measuring thyroid hormone and TSH levels are needed to make a correct diagnosis. In some cases, antibody tests are also helpful.

Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH)TSH levels are the most important indicator of hypothyroidism. However, certain medical conditions, such as pregnancy, can affect thyroid hormone levels. In general, TSH results indicate the following:

- TSH levels over 10mU/L indicate overt hypothyroidism. People will usually need thyroxine (T4) replacement therapy.

- TSH levels between 4.5 and 10 mU/L indicate mildly underactive (subclinical) hypothyroidism. People should be retested every 6 to 12 months. The decision to treat is made on an individual basis.

- TSH levels between 0.45 and 4.5 mU/L indicate normal thyroid function.

- TSH levels under 0.45 mU/L suggest hyperthyroidism, which is overactive thyroid, or overtreated hypothyroidism.

If TSH levels appear abnormal, your provider may order a free T4 test. Low levels of T4 suggest hypothyroidism. A high TSH level and a low T4 level confirm a diagnosis of primary hypothyroidism.

Much less commonly, people will have normal TSH levels but low T4 levels. This combination suggests secondary hypothyroidism, a condition where thyroid function is impaired due to problems in the pituitary gland.

Antithyroid AntibodiesA test for antithyroid antibodies may be ordered if your provider suspects your hypothyroidism is due to the autoimmune condition Hashimoto thyroiditis. This test usually checks for thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody. An alternate test checks for thyroglobulin antibodies.

High levels of these antibodies indicate that the immune system is attacking the thyroid and may interfere with its function. If your test results show high levels of antithyroid antibodies, but your TSH and T4 levels are within normal limits, your provider will probably delay treatment until your thyroid function levels indicate an underactive thyroid. Many people with positive thyroid antibodies never develop overt hypothyroidism.

Other Blood TestsBecause hypothyroidism is often associated with high cholesterol levels, anemia, and other health problems, your provider may order other tests to detect them.

Imaging Tests

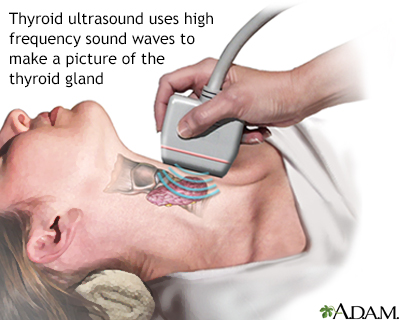

UltrasoundAn ultrasound test uses sound waves to visualize the thyroid gland. It can evaluate swelling in the thyroid, show if any thyroid nodules (lumps) are present, and if they are solid, filled with fluid, or have signs of cancer. Thyroid nodules are very common and are usually benign. The ultrasound and other imaging tests do not measure thyroid function.

More Advanced Imaging Tests

Other tests used for visualizing the thyroid gland include computed tomography (CT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Radiologic Tests

Radioactive Iodine Uptake Test (RAIU Test)The thyroid uptake test is a nuclear medicine test that uses a radioactive iodine tracer. You will drink a liquid or capsule containing the radioactive iodine. A special gamma probe is placed on the neck to measure how much of the tracer the thyroid absorbs from the blood. A low uptake indicates hypothyroidism.

Thyroid Scan (Scintigraphy)Thyroid scintigraphy, or scan, is another nuclear medicine test. It provides pictures that help the provider evaluate the structure and function of the thyroid gland. This procedure also uses the radioactive iodine tracer. A special gamma camera then takes images of the thyroid. Thyroid scans may be performed to evaluate a goiter (swollen thyroid) or thyroid nodules. They can help identify areas of the gland that may have cancer.

Needle Aspiration Biopsy

Needle aspiration biopsy is used to obtain thyroid cells for microscopic evaluation. It may be useful to rule out thyroid cancer in people with thyroid nodules, abnormal findings on a thyroid scan or ultrasound, or those who have a goiter that is large or feels unusual on physical exam. Much like drawing blood, the provider inserts a small needle into the thyroid gland and draws cells from the gland into a syringe. The cells are put onto a slide, stained, and examined under a microscope.

Screening Recommendations for Hypothyroidism

Professional organizations differ widely on hypothyroidism screening recommendations. Most do not recommend widespread routine screening for healthy nonpregnant adults who have no symptoms. The US preventive service (USPSTF) concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the thyroid screening in nonpregnant, asymptomatic adults.

The American Thyroid Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommend considering screening for hypothyroidism in patients older than 60 years. They also recommend "aggressive case finding" in women who are planning pregnancy and in persons who are at increased risk for hypothyroidism, such as those with personal or familial history of autoimmune disease.

Screening in Pregnant WomenCurrent guidelines recommend screening women before or during pregnancy based on their symptoms or medical history. Factors that indicate screening is necessary include:

- History of thyroid disease, goiter, type 1 diabetes or other autoimmune illnesses

- History of miscarriages

- History of head and neck radiation or surgery

Women with these factors should have their thyroid checked before pregnancy, or within the first weeks of pregnancy, and should be retested during each trimester.

Screening in InfantsIn the U.S., most newborns are routinely screened for hypothyroidism using a thyroid blood test.

Ruling out Other Disorders

Hypothyroidism can mimic other medical conditions.

Age-Related DisordersSome symptoms of hypothyroidism and aging are very similar. Menopausal symptoms often resemble hypothyroidism. Many other problems related to aging, such as vitamin deficiencies, Parkinson and Alzheimer diseases, and arthritis, also have characteristics that can mimic hypothyroidism.

DepressionDrowsiness, fatigue, and difficulty concentrating are signs of clinical depression as well as hypothyroidism. Depression and hypothyroidism often coexist, particularly in older women, so diagnosing one does not rule out the presence of the other.

Chronic Kidney DiseaseEdema, sallow complexion, and drowsiness may also be present in chronic kidney disease.

Treatment

Hypothyroidism cannot be cured, but the condition can be controlled by taking daily synthetic thyroxine (T4) medication, most often for life.

Treating Overt HypothyroidismIn general, health care providers prescribe thyroid medication for people who have TSH levels above 10 mU/L. The exact dosage depends on many factors, including:

- Age.

- Weight.

- Severity of symptoms.

- Presence of other medical conditions that may benefit from or be worsened by thyroid replacement therapy.

- Pregnancy status.

- Medications that the person is also taking to treat other conditions, which may interfere with absorption of thyroxine (T4) from the small intestine.

Considerable debate exists about whether to treat people with subclinical hypothyroidism (TSH levels in the upper range of normal levels or slightly higher than normal, normal T4 levels, and no obvious symptoms). In general, current evidence does not support treating most people in this group.

Providers who recommend against treatment argue that thyroid levels can vary widely, and subclinical hypothyroidism may not persist. In such cases, overtreatment leading to hyperthyroidism is a real risk. Most professional organizations recommend against treating subclinical hypothyroidism and suggest monitoring for changes in thyroid levels that would warrant treatment.

Your provider may recommend treating subclinical hypothyroidism in the presence of other factors, including:

- Pregnancy

- Infertility

- Goiter

- Heart disease risk factors, including high total or LDL (bad) cholesterol levels

Treatment of Special Cases

Treating Older PeopleThyroid dysfunction is common in older people, with most having subclinical hypothyroidism. There is no evidence that this condition poses any great harm in this population, and most providers recommend treating only high-risk patients. Older people, particularly those with heart conditions, usually start with very low doses of thyroid replacement, since thyroid hormone may cause angina or even a heart attack. People who have heart disease must take lower-than-average maintenance doses.

Treating Newborns and Infants with HypothyroidismBabies born with hypothyroidism (congenital hypothyroidism) should be treated with levothyroxine (T4) as soon as possible to prevent complications. Early treatment can help improve cognitive and other developmental factors. However, even with early treatment, mild problems in mental functioning may last into adulthood. In general, children born with milder forms of hypothyroidism will fare better than those who have more severe forms.

Oral levothyroxine (T4) can usually restore normal thyroid hormone levels within 1 to 2 weeks. It is critical that normal levels are achieved within a 2-week period. If thyroid function is not normalized within 2 weeks, it can pose greater risks for developmental problems. Infants should continue to be monitored closely to be sure that thyroxine levels remain as consistently close to normal as possible. These children need to continue lifelong thyroid hormone treatments.

Treatment During Pregnancy and for Postpartum ThyroiditisWomen who have hypothyroidism before becoming pregnant may need to increase their dose of levothyroxine during pregnancy. Women who are first diagnosed with overt hypothyroidism during pregnancy should be treated immediately, with quick acceleration to therapeutic levels. Providers often recommend treating women who are diagnosed with subclinical hypothyroidism while pregnant, although the benefit is not well proven.

Women with subclinical hypothyroidism who are not treated should be evaluated throughout the pregnancy to see if they progress to overt hypothyroidism. There are no risks to the developing baby when the pregnant woman takes appropriate doses of thyroid hormones. The pregnant woman with hypothyroidism should be monitored regularly (thyroid tests every 4 weeks during the first half of pregnancy) and medication doses adjusted as necessary. If postpartum thyroiditis develops after delivery, any thyroid medication should be reduced or temporarily stopped during this period.

Women who are considering becoming pregnant should take a prenatal multivitamin that contains 150 to 200 micrograms of iodine in the form of potassium iodide or iodate. (Not all prenatal vitamins contain this recommended amount, so check the label.) Women who are pregnant should also take a multivitamin containing 150 to 200 micrograms of iodine. Breastfeeding women need to maintain a daily intake of 250 micrograms of iodine to ensure that their infants are provided with 100 micrograms of iodine a day.

Prevention of iodine deficiencySince iodine is indispensable for the synthesis of thyroid hormones in the body, iodine deficiency is a cause of hypothyroidism. An adequate dietary intake of iodine prevents iodine deficiency and reduces the risk for hypothyroidism. The following are U.S. recommended daily allowance (RDA) or adequate intake values for iodine:

- Birth to 6 months: 110 micrograms per day

- 7 to 12 months: 130 micrograms per day

- 1 to 8 years: 90 micrograms per day

- 9 to 13 years: 120 micrograms per day

- 14 years and above: 150 micrograms per day

- Pregnant women: 220 micrograms per day

- Lactating women: 290 micrograms per day

Iodine deficiency used to be prevalent in many countries worldwide. Iodization of salt implemented through country-level programs has significantly reduced the number of people with iodine deficiency worldwide. However, iodine deficiency remains the world's most prevalent, although preventable, cause of brain damage.

Dietary sources of iodine include:

- Fish and seafood

- Milk and dairy products

- Eggs

- Seaweed

- Iodized salt and other iodine fortified foods

Additionally, many multivitamin or other supplements also contain the RDA of iodine.

Medications

Thyroid Hormone Replacement

The goal of thyroid drug therapy is to provide the body with replacement thyroid hormone when the gland is not able to produce enough itself.

A synthetic thyroid hormone called levothyroxine is the treatment of choice for hypothyroidism. This drug is a synthetic derivative of T4 (thyroxine), and it normalizes blood levels of TSH, T4, and T3.

Brand NamesA number of levothyroxine brands are available in different countries and regions of the world, such as Synthroid, Euthyrox, L-Thyroxin, and others. Before synthetic thyroid hormones were first manufactured, hypothyroidism used to be treated with dried powder thyroid hormone made from animal glands. In the past, manufacturers of synthetic levothyroxine did not need to meet as strict standards as in the production of other drugs. This resulted in thyroid products with varying quality and potency. The FDA has since issued stronger requirements that have largely corrected this problem.

Generics versus Brand-Name ProductsThe American Thyroid Association (ATA) recommends the prescription of brand-name levothyroxine, or alternatively maintenance of the same generic preparation (for example, maintenance of an identifiable formulation of levothyroxine). ATA also advices sticking with the same brand or preparation, since potency often varies from one drug to the next.

T3 and T4 CombinationsTriiodothyronine (T3), the other important thyroid hormone, is not ordinarily prescribed except under special circumstances. Most people respond well to thyroxine (T4) alone, which is converted in the body into T3. In addition, the use of T3 may cause disturbances in heart rhythms. Some people treated only with thyroxine continue to have mood and memory problems or other symptoms, however.

Combination products containing T4 and T3, such as liotrix (Thyrolar), are available, but there is controversy concerning their benefits. Research indicates that T3 and T4 together do not work better than T4 alone. It does not appear that combination products offer any advantage for normalizing TSH levels.

Levothyroxine Regimens

Levothyroxine needs to be taken only once a day. Although many people feel better after only 2 to 3 weeks of treatment, levothyroxine is slowly assimilated by body organs, so it usually takes up to 6 weeks before symptoms improve in adults. The speed at which specific symptoms improve varies:

- Weight loss, less puffiness, and improved pulse usually occur early in the treatment.

- Improvements in anemia and skin, hair, and voice tone may take a few months.

- High LDL (bad) cholesterol levels decline very gradually. HDL (good) cholesterol levels are not affected by treatment.

- Goiter size declines very slowly, and some people may need high-dose thyroid hormone (called suppressive thyroid therapy) for a short period.

Levothyroxine can help reduce blood pressure in people who have both hypothyroidism and hypertension, although blood pressure medications may still be needed.

Appropriate Dosage LevelsInitial dosage levels are determined on an individual basis and can vary widely, depending on a person's age, medical condition, other drugs they are taking, and, in women, whether or not they are pregnant. For example, pregnant women with hypothyroidism need higher replacement dosage than normal.

- Starting out. Most people need to build up gradually until they reach a maintenance dose. In uncomplicated cases, the dose typically starts at 50 micrograms (mcg) per day, which then increases in 4 to 6 week intervals until reaching the maintenance dose which produces normal TSH levels. Seniors and those with heart disease may start at 12.5 to 25 mcg per day. On the other hand, young adults who have not had hypothyroidism for very long might be able to tolerate a full maintenance dosage right away.

- Maintenance dose. Maintenance daily dose for most people averages 112 mcg, but it can vary from 75 to 260 mcg. If conditions such as pregnancy, surgery, or other drugs alter hormone levels, the person's thyroid hormone needs will have to be reassessed.

Because thyroid replacement therapy is usually lifelong, setting up a regular daily routine is helpful. Here are some tips to remember:

- Establish a habit of taking the medication at the same time each day. This may help prevent missed doses. It's best to take levothyroxine on an empty stomach usually 30 to 60 minutes before eating breakfast.

- If you miss a dose of your medicine, take it as soon as you can. If it is almost time for your next dose, take your medicine then and skip the missed dose. Do not use extra medicine to make up for a missed dose.

- Fiber and common daily supplements such as calcium supplements, calcium aluminum-containing antacids or iron can interfere with levothyroxine absorption, as can medications such as proton pump inhibitors and bile acid sequestrants (that are used to lower cholesterol).

- Foods like soy and walnuts can also affect absorption. It is best to take your thyroid medication 1 hour before or 2 hours after taking supplements or eating high-fiber foods like oatmeal or calcium-containing foods like dairy products.

Many factors can cause changes that require modifications to levothyroxine dosages. A dose that is appropriate one year may be too low the next. To maintain normal thyroid levels, some people may need to take gradually increasing doses of thyroid hormone. Your provider will re-evaluate you 6 months after your TSH levels have normalized, and then once a year thereafter.

Specific factors, such as changes in health or diet, new medications for other conditions, or simply switching brands, can also cause changes in thyroid hormone levels that require different doses. If you change dose levels or levothyroxine brands, your thyroid levels should be checked again at least 6 weeks later.

Monitoring Levothyroxine Treatment

Because levothyroxine is identical to the thyroxine the body manufactures, side effects are rare. Over- or underdosing is fairly common, although rarely serious in the short term.

Symptoms of underdosing are the same hypothyroidism symptoms originally experienced and may include:

- Sluggishness, fatigue, mental dullness

- Feeling cold

- Weight gain

- Constipation

- Muscle cramps

Symptoms of overdosing include:

- Heart symptoms (rapid or irregular heartbeat, palpitations, and wide variations in pulse; possible angina or heart failure)

- Agitation, tremor, nervousness, insomnia

- Feeling warm, flushed skin, intolerance to heat

- Metabolic symptoms (change in appetite, weight loss)

- Diarrhea

Overdosing can cause symptoms of hyperthyroidism. A person with too much thyroid hormone in the blood is at increased risk for abnormal heart rhythms, rapid heartbeat, heart failure, and possibly a heart attack if there is underlying heart disease. Excess thyroid hormone is particularly dangerous in newborns, and their drug levels must be carefully monitored to avoid brain damage. Long term overdosing may also lead to thinning of the bones or osteoporosis.

Drug Interactions with LevothyroxineMany drugs interact with levothyroxine. Important interactions include:

- Amphetamines

- Anticoagulants (blood thinners)

- Tricyclic antidepressants

- Anti-anxiety drugs

- Arthritis medications

- Aspirin

- Beta-blockers

- Insulin

- Oral contraceptives (estrogens)

- Testosterone

- Digoxin

- Certain cancer drugs

- Anticonvulsants (phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine)

- Rifampin (antibiotic used to treat or prevent tuberculosis)

- Sertraline (antidepressant)

- Iron and calcium supplements

- Proton pump inhibitors (which reduce stomach acid)

- Bile acid sequestrants (which lower cholesterol levels)

Large amounts of dietary fiber may reduce the drug's effectiveness. People whose diets are consistently high in fiber may need larger doses of the drug. Since thyroid hormones regulate metabolism and can affect the actions of a number of medications, dosages may also need to be adjusted if a person is being treated for other conditions. Even changing thyroxine brands can have an effect.

People who require much higher than average doses of thyroxine to normalize their hormone levels may need to be evaluated for several conditions that interfere with absorption of levothyroxine from the small intestine, such as celiac disease and Helicobacter pylori gastritis. They may also have had surgery in the past to remove portions of their intestines.

Inappropriate Use of Thyroid Hormone

Thyroid hormone replacement is sometimes prescribed inappropriately. It should be used only to treat diagnosed hypothyroidism.

Inappropriate uses of thyroid hormones include to induce weight loss, to reduce high cholesterol levels, or to treat so-called metabolic insufficiency. Vague symptoms suggesting low metabolism, such as dry skin, fatigue, slight anemia, constipation, depression, and apathy should not be treated indiscriminately with thyroid hormone. Some patients with severe depression are treated with thyroid hormone even though their thyroid blood tests are normal.

Doctors who specialize in thyroid disorders are concerned with an increasing trend of treating people who have subclinical hypothyroidism. Overtreatment of borderline hypothyroidism can be risky, especially for older people.

No evidence exists that thyroid hormone therapy is beneficial unless the person has proven clinical hypothyroidism. Indiscriminate use of thyroid hormones can weaken muscles, possibly increase the risk for fractures, and, over the long term, negatively affect the heart.

Resources

- American Thyroid Association -- www.thyroid.org

- Hormone Health Network -- admin.hormone.org/

- Endocrine Society -- www.endocrine.org/

References

Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent GA, et al. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and the postpartum. Thyroid. 2017;27(3):315-389. PMID: 28056690 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28056690.

Bekkering GE, Agoritsas T, Lytvyn L, et al. Thyroid hormones treatment for subclinical hypothyroidism: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2019;365:l2006. PMID: 31088853 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31088853.

Biondi B, Cappola AR, Cooper DS. Subclinical hypothyroidism: A review. JAMA. 2019;322(2):153-160. PMID: 31287527 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31287527.

Brent GA, Weetman AP. Hypothyroidism and thyroiditis. In: Melmed S, Auchus RJ, Goldfine AB, Koenig RJ, Rosen CJ, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 14th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 13.

Casey BM, Thom EA, Peaceman AM, et al. Treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism or hypothyroxinemia in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(9):815-825. PMID: 28249134 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28249134.

Chaker L, Bianco AC, Jonklaas J, Peeters RP. Hypothyroidism. Lancet. 2017;390(10101):1550-1562. PMID: 28336049 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28336049.

De Groot L, Abalovich M, Alexander EK, et al. Management of thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy and postpartum: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(8):2543-2565. PMID: 22869843 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22869843.

Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(6):988-1028. PMID: 23246686 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23246686.

Harding KB, Peña-Rosas JP, Webster AC, et al. Iodine supplementation for women during the preconception, pregnancy and postpartum period. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3:CD011761. PMID: 28260263 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28260263.

Hennessey JV, Espaillat R. Diagnosis and management of subclinical hypothyroidism in elderly adults: a review of the Literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(8):1663-1673. PMID: 26200184 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26200184.

Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism: prepared by the American Thyroid Association Task Force on thyroid hormone replacement. Thyroid. 2014;24(12):1670-1751. PMID: 25266247 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25266247.

LeFevre ML; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for thyroid dysfunction: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(9):641-650. PMID: 25798805 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25798805.

Mestman JH. Thyroid and parathyroid diseases in pregnancy. In: Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, et al, eds. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 42.

Papaleontiou M, Esfandiari NH. Disorders of the thyroid. In: Fillit HM, Rockwood K, Young J, eds. Brocklehurst's Textbook of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 88.

Rugge JB, Bougatsos C, Chou R. Screening and treatment of thyroid dysfunction: An evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(1):35-45. PMID: 25347444 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25347444.

Wassner AJ, Smith JR. Hypothyroidism. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 581.

Wiersinga WM. Hypothyroidism and myxedema coma. In: Jameson JL, De Groot LJ, de Kretser DM, et al, eds. Endocrinology: Adult and Pediatric. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016:chap 88.

Review Date: 9/7/2019

Reviewed By: Brent Wisse, MD, board certified in Metabolism/Endocrinology, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.