Peripheral artery disease and intermittent claudication - InDepth

Peripheral vascular disease - InDepth; Peripheral arterial disease - InDepth; PVD - InDepth; PAD - InDepth; Arteriosclerosis obliterans - InDepth; Blockage of leg arteries - InDepth; Claudication - InDepth; Intermittent claudication - InDepth; Vaso-occlusive disease of the legs - InDepth; Arterial insufficiency of the legs - InDepth; Recurrent leg pain and cramping - InDepth; Calf pain with exercise - InDepthAn in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, and treatment of peripheral artery disease (PAD).

Highlights

Peripheral Artery Disease

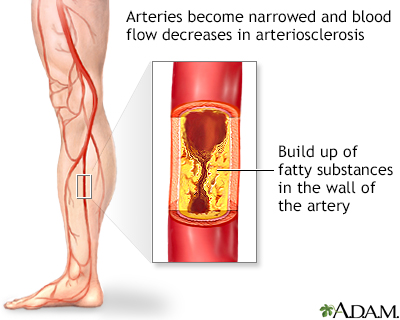

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is a type of atherosclerosis, the condition that causes narrowing of the arteries by cholesterol-rich material called plaque. PAD refers to atherosclerosis of arteries in the limbs (most often the legs). Because PAD interferes with circulation, in severe cases procedures may be required to improve blood flow. When PAD is very severe, it can increase the risk for gangrene and can result in a need for amputation. People with PAD are also at increased risk for complications in other arteries, which can lead to heart attacks and stroke.

Risk Factors of PAD

The main risk factors of PAD include:

- Smoking

- Diabetes

- Unhealthy cholesterol and lipid levels

- High blood pressure

- Advancing age

Symptoms

Many people with PAD do not have symptoms. When symptoms do occur, leg cramp pain (intermittent claudication) is the main symptom. At first, this symptom occurs with predictable amounts of exercise (walking a certain distance, up a hill or stairs), and disappears when at rest. When PAD becomes more severe, symptoms can include:

- Pain or tingling in the calf, feet, or toes, even at rest

- Weakened calf muscles

- Painful non-bleeding ulcers on the feet or toes that do not heal

Treatment

Treatment for PAD includes lifestyle measures, medications that help reduce symptoms and prevent disease progression, and surgery. These include:

- Smoking cessation.

- Regular exercise, which is essential for patients with mild-to-moderate PAD.

- Heart-healthy diet, low in saturated fat and sodium, to reduce unhealthy cholesterol levels and improve blood pressure.

- Medications to help control high blood pressure and cholesterol. Other important drugs include antiplatelet medications to prevent blood clots.

- In severe cases, procedures may be needed to open blocked blood vessels.

Introduction

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) occurs when the arteries in the extremities (usually legs and feet, sometimes arms and hands) become clogged with fat, cells, and other substances, which accumulate and harden into plaque. The build-up of plaque causes the arteries to become narrow and stiff, obstructing blood flow. This hardening and narrowing of the arteries is called atherosclerosis. (Atherosclerosis that affects arteries to the heart and brain is the major process leading to heart disease and stroke.)PAD most often occurs in the legs. PAD is a type of peripheral vascular disease, which also includes carotid artery disease, renal artery disease, aortic disease, venous problems, and some other conditions, such as vasculitis.

Symptoms

People with PAD may or may not have symptoms. Because symptoms may be mild or even absent, many cases of PAD go undiagnosed.

Intermittent Claudication

Claudication comes from the Latin word "to limp." Claudication is leg cramp pain that occurs during exercise, especially walking. The pain is due to insufficient blood flow in the legs (caused by narrowed or completely blocked arteries) to supply oxygen to the working muscles. Intermittent means the pain comes and goes. Intermittent claudication is the most typical symptom of PAD. About one third to one half of people with PAD have this symptom.

Symptoms may be described as pain, ache, cramping, a sense of fatigue, or nonspecific discomfort that occurs with exercise. There is no discomfort while standing. Symptoms go away rapidly with rest. If exercise is restarted, pain will come back after a while and the cycle is repeated, such that the person can predict the distance after which symptoms reoccur. At first, symptoms may only initially develop when walking uphill, walking faster, or walking longer distances.

Intermittent claudication symptoms are most common in the calf muscles. This is because the most frequently affected artery is the popliteal artery, which branches off from the femoral artery (the major artery in the thigh). The popliteal artery continues below the knee where it carries blood to the muscles in the calf and foot. Talk to your doctor about any leg or thigh pain you have.People may experience muscle pain in one leg or in both legs. People may also have fatigue or pain in the thighs and buttocks.

Critical Limb Ischemia

In advanced cases of PAD, the arteries are so blocked that even rest does not help. Leg pain that continues when lying down is called ischemic rest pain. It is caused by critical limb ischemia, the medical term for insufficient blood flow through arteries of the legs to the muscles and other tissues. Critical limb ischemia is a chronic condition and a very serious form of advanced PAD.

Typical symptoms of critical limb ischemia may include:

- Pain or tingling in the foot or toes, which may be so severe that even the weight of clothes or bed sheets cause or worsen the discomfort

- Pain worsens when the leg is elevated and improves by dangling legs over the side of the bed

People with critical limb ischemia are at risk for developing non-healing skin ulcers and gangrene (tissue death). In severe cases, amputation may be required.

Other signs of advanced PAD can include:

- Calf muscles that atrophy (shrink)

- Hair loss over the toes and feet

- Thick toenails

- Shiny, tight skin

- Painful non-bleeding ulcers on the feet or toes (usually black) that are slow to heal

Sometimes, blood clots form in the arteries in the legs, producing abrupt and severe symptoms (acute occlusion).

Risk Factors

About 8 million American adults have PAD, and the prevalence of the disease is increasing worldwide. Men and women are equally susceptible although women face a greater risk for limb loss. African Americans have twice the risk for PAD as white people. Between 12% to 20% of people over age 65 suffer from the condition.

PAD Risk Factors

The risk factors for PAD are the same as those for heart disease and stroke. Smoking and high cholesterol levels increase the risk for PAD progression in large blood vessels (such as the legs), while diabetes increases the risk for PAD in small blood vessels (such as the feet). Quitting smoking and controlling cholesterol and high blood pressure are the best ways to slow PAD progression.

The most important risk factors for PAD include:

Smoking.

Smoking is an important risk factor for PAD. Smoking is associated with a higher risk for PAD complications, and smoking even a few cigarettes a day can interfere with PAD treatment. Smoking increases the risk for PAD by 2 to 25 times, with the danger being higher when other risk factors are present. Between 80% to 90% of people with PAD are current or former smokers. Progression to a more critical state of illness is likely for patients who continue to smoke.Smoking

An in-depth report on the health risks of smoking and how to quit.

Image

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article Diabetes.

People with type 2 diabetes have 3 to 4 times the normal risk for PAD and intermittent claudication. In fact, their risk for PAD is higher than their risk for heart disease. People with type 2 diabetes also tend to develop PAD at an earlier age and have more severe cases. People with both diabetes and PAD are at high risk for complications in the feet and ankles. Poor blood sugar (glucose) control increases the risk of developing PAD.Metabolic syndrome.

This term refers to a constellation of findings, including obesity, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and insulin resistance. People with metabolic syndrome are also at increased risk for PAD.Unhealthy cholesterol and lipid levels.

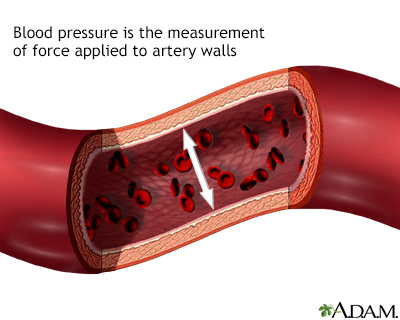

The risk for PAD is increased in patients with high total cholesterol levels. Levels of HDL (good cholesterol) below 40 mg/dL and high triglyceride levels also increase the risk for PAD.Hypertension.

High blood pressure, especially when combined with other cardiovascular risk factors, puts stress on the arteries and increases the chances for PAD. High blood pressure is generally considered to be a reading greater than 130 systolic and 80 diastolic (130/80 mm Hg).High blood pressure

An in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of high blood pressure.

Image

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Blood pressure is the force applied against the walls of the arteries as the heart pumps blood through the body. The pressure is determined by the force and amount of blood pumped and the size and flexibility of the arteries.

Obesity and Physical Inactivity.

Obesity and lack of exercise are risk factors for heart disease and diabetes, and contribute to increased risk for PAD. Increased physical activity is one of the most important measures for both preventing and treating PAD. Losing excess weight can help improve cholesterol, blood pressure, and other atherosclerotic disease risk factors.Family history of heart and artery disease.

Genetic factors that cause specific lipid and cholesterol abnormalities may increase the risk for PAD.Age.

PAD occurs more frequently in people over age 50 and particularly affects those ages 65 years and older.Race and Ethnicity.

African Americans are at highest risk for PAD. They are twice as likely to develop PAD as white people.

Diagnosis

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is greatly under-diagnosed. Many people do not report symptoms or may not even have symptoms.

People should be checked for PAD if they have leg pain during walking, or ulcers on their legs. People who may not have symptoms but who should be screened for PAD include those with coronary artery disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or people who have had a previous stroke.

Doctors use the ankle-brachial index (ABI) to screen for PAD. The United States Preventive Services Task Force has determined that the current evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation on ABI screening in asymptomatic patients.

Physical Examination

The doctor should check for high blood pressure, heart abnormalities, blockage(s) in the artery in the neck, and abdominal aneurysms. The doctor should also examine the skin of the legs and feet for color changes, ulcers, infection, or injuries, and check the pulse of the arteries in the leg.

- The skin may appear thin, dry, shiny, or hairless.

- Nails may become brittle, thickened, or ridged.

- The area of the leg below any blockage may feel cooler to the touch.

Your health care provider may do the following during physical exam:

- While you are lying down, your leg will be elevated. If the blood supply is healthy, the leg will remain pink. If not, the skin and leg will be pale (pallor).

- The leg will then be lowered below the level of your heart. For those with PAD, the leg will take on a dusky flush or blueish redness. This coloring will usually begin at the toes and spread toward your upper leg.

If someone has a sudden blockage of an artery, the leg or foot may appear chalky white.

Ankle-Brachial Index

The standard diagnostic and screening test for peripheral artery disease is a calculation called the ankle-brachial index. The procedure is done as follows:

- The doctor or technician measures the systolic blood pressure of both arms while the patient is lying down. (The systolic pressure is the "top" number in a blood pressure measurement. It is the force that blood exerts on the artery walls as the heart contracts to pump out the blood. For example, in a blood pressure reading of 120/80, 120 is the systolic number.)

- The doctor or technician then puts blood pressure cuffs on four different locations on each leg and passes a Doppler probe over arteries in the foot. The signal emitted from the strongest artery is recorded as the cuffs are inflated and deflated. This is the ankle's systolic pressure.

The doctor divides the systolic pressure in the ankle by the systolic pressure in the arm. The result is called the ankle-brachial index (ABI), also called ankle-arm pressure index (API).

Who should undergo this test?

- Screening should be performed on those with symptoms or findings suggestive of PAD.

- Screening can be considered for those over 70 years, smokers, diabetic patients, those with other types of cardiovascular diseases, and those with an abnormal pulse on physical exam.

- Screening people without risk factors and without symptoms of PAD is generally not recommended.

What the results mean:

ABI over 0.90.

An ABI result from 1.00 to 1.40 is considered normal. Results from 0.91 to 0.99 are considered borderline. If results fall in the borderline range, the person takes a treadmill test and another ABI measurement. If the API index drops after exercise, the doctor makes a diagnosis of peripheral artery disease. ABI may be normal or even above the normal range (over 1.4) in people who have PAD but whose arteries are significantly thickened and calcified, such as some older adults or people with diabetes. If PAD is strongly suspected in these cases, the toe-brachial index (TBI) may be used instead.ABI 0.40 to 0.90.

ABI measurements below 0.90 are considered abnormal. Measurements from 0.40 to 0.90 indicate mild-to-moderate impairment and symptoms such as leg pain.ABI less than 0.40.

ABI measurements below 0.40 indicate very severe blockage in the leg arteries (critical limb ischemia) and a risk for gangrene. People should take precautions to avoid foot injuries, which can increase the risk for non-healing wounds and gangrene.

Treadmill Test

The ABI test is often followed by a treadmill test to find out how exercise affects the blood flow in your extremities. The treadmill test is also useful for determining the severity of the pain while walking and assessing the effectiveness of treatments.

Ultrasound Imaging

Ultrasound imaging is used to provide an anatomic view of the arteries and report on blood velocity and flow characteristics. A duplex ultrasound combines traditional ultrasound with Doppler ultrasound. These tests can also help identify areas of arterial blockage and help doctors decide which patients may need surgical interventions.

Angiography, Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA), and Computed Tomography Angiography (CTA)

Before considering invasive procedures to treat peripheral artery disease, the surgeon needs a better understanding of which arteries are involved, how severe the blockage is, and the state of the blood vessels surrounding the blockage. In the past, invasive or conventional angiography was typically performed. This type of angiogram uses dye, which is injected through a catheter that is inserted in the groin or arm.

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is a type of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). It provides a non-invasive alternative to a traditional angiogram. The MRA uses a magnetic field and radiofrequency waves instead of radiation to provide pictures of arteries and blood vessels. People are given gadolinium (a contrast material) through an IV to improve the image quality. In many medical centers, MRA is considered almost or as accurate as invasive angiography and will frequently be the only test required.

Another technology called computed tomography angiography (CTA) uses x-rays to visualize blood flow in arteries throughout the body. This technique is also highly effective in diagnosing PAD.

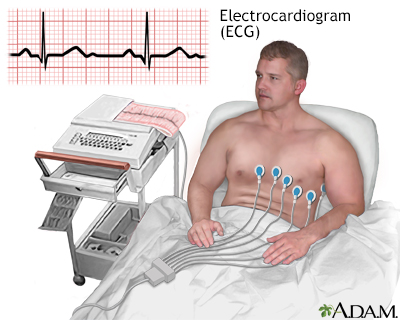

Tests for Detecting Heart Disease

People with suspected PAD should have an electrocardiogram (ECG) and other tests that can detect heart problems.

The electrocardiogram (ECG) is used extensively in the diagnosis of heart disease, from congenital heart disease in infants to myocardial infarction and myocarditis in adults. There are several different types of electrocardiograms.

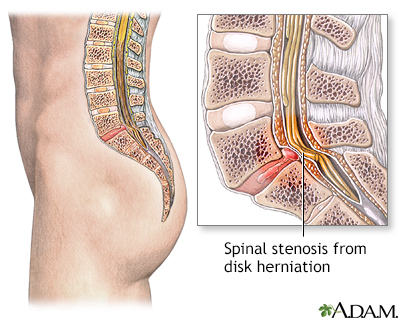

Ruling Out Other Disorders with Similar Symptoms

A number of other tests may be ordered to rule out disorders with similar symptoms. Such conditions include:

- Arthritis

- Anemia

- Spinal stenosis -- narrowing of the spinal canal causing leg or lower back pain

- Deep vein thrombosis -- blood clots in the deep veins of the legs

- Peripheral neuropathy -- nerve damage in the legs and feet, usually in people with diabetes

- Night cramps in older people that are not due to problems in blood vessels

- Muscle entrapment of the arteries or kinks in the arteries in the leg -- typically occurs in young athletes

Complications

Coronary Artery Disease and Stroke

People with peripheral artery disease (PAD) have the same risk of death from heart events or stroke as people already diagnosed with heart disease. The risk increases as PAD gets worse. The worse the leg condition, the poorer is the overall health of the patient.

If people have blood clots and blockages in other arteries (brain, heart) as well as the legs, the risk for any vascular complication involving the heart, the brain, or the leg arteries increases much more.

Gangrene and Amputation

Severe advanced PAD can cause gangrene (tissue death) that leads to limb amputation. These conditions may result from critical limb ischemia (chronic blockage of arteries in the legs) or acute occlusion (sudden development of blood clot in a major artery of the leg.).

Poor Physical and Mental Functioning

Peripheral artery disease can significantly impair daily physical functioning. Leg pain can limit physical activity, cause unsteadiness, and increase the risk for falling. PAD may also cause erectile dysfunction and it is associated with mental decline.

Treatment

Symptoms and complications of PAD are likely to progress over time. Overall, more than one fifth of patients who present with symptoms of PAD will progress and experience problems or complications. However, the presence of certain risk factors may predict a more rapid progression. These risk factors include:

- Increasing age, smoking, and the presence of heart disease, stroke or TIA, or other health problems related to narrowing of the arteries.

- Gender may play a role, with male sex increasing the risk for worsening PAD.

There are 2 treatment goals for PAD and claudication.

- Manage the pain of intermittent claudication, improve functioning, and prevent PAD from getting worse so that gangrene does not occur.

- Reduce the risk for cardiovascular disease (heart attack and stroke).

Lifestyle changes such as smoking cessation and exercise, are critical for every person with PAD. Medication is often required to improve function and protect the heart. In very severe cases, surgery may be needed to improve blood flow.

Treatment for PAD also involves managing the medical conditions (diabetes, high cholesterol, and high blood pressure) that often accompany it.

Managing Diabetes

People with diabetes (type 1 or type 2) need to strictly control their blood sugar (glucose) levels. Poor glycemic control is associated with vascular and circulation complications such as PAD. People should aim for an A1c level around 7%. The A1c test measures a person's average blood sugar over the past 2 to 3 months. People with diabetes need to follow certain dietary restrictions. Many different types of medications are used to control blood sugar levels.

Managing Unhealthy Cholesterol and Lipid Levels

It is very important for people with PAD to keep their LDL (bad cholesterol) levels controlled. The latest guidelines recommend high-potency statin therapy to control cholesterol in people with PAD. Unhealthy cholesterol levels are major contributors to atherosclerosis, the common factor in PAD and heart disease.

People should follow lifestyle principles to reduce unhealthy cholesterol levels including consuming a heart-healthy diet, engaging in regular physical activity (the AHA recommends 150 minutes of moderate activity or 75 minutes of vigorous activity per week), and maintaining a healthy body weight.

Managing High Blood Pressure

Most people with PAD should aim for blood pressure less than 130/80 mm Hg. But people with diabetes may need to have a lower systolic (top number) or diastolic (bottom number) goal. Ask your doctor what your target blood pressure goal should be.

People should be sure to follow dietary measures to reduce sodium (salt) and increase potassium intake. The DASH diet is a good example of a diet plan based on these principles.

Various medications are used to control high blood pressure (hypertension). There is some evidence that the best drugs for people with high blood pressure and PAD may be angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.

Lifestyle Changes

Quit Smoking

People who smoke should quit, and everyone should avoid second-hand smoke. Smoking is one of the primary risk factors for PAD and a major cause of complications. Quitting smoking may not make leg pain go away, at least not in the short term, but it certainly may keep blockages from getting worse. Continued smoking is a major reason why people progress from milder forms of PAD to critical limb ischemia involving severe pain, skin ulcers, and possible amputation. Smoking cessation also reduces the risk to the heart and brain.

Exercise

Exercise is second only to avoiding tobacco as the most important lifestyle measure for treating, and preventing, PAD.

Exercise to Help the HeartThe benefits of regular moderate exercise for the heart are undisputed. People who maintain an active lifestyle have a much lower risk of developing heart disease than do sedentary people. According to the American Heart Association, patients with PAD who are physically active have death rates that are a third of those who are less physically active.

Exercise Training to Improve Blood Flow in the LegsExercise training improves blood flow in the legs and, in some cases, can work as well as medications and surgical procedures in increasing pain-free walking distance. To maintain benefits, exercise must be regular and consistent. A regular walking program, either outside or on a treadmill, is the best type of exercise for people with PAD and can significantly slow the rate of functional decline.

For people with intermittent claudication who find that their leg cramps make it difficult to walk or participate in lower-extremity exercise, upper-body aerobic exercise can still provide benefits.

Eat Right

The goals of a heart-healthy diet are to:

- Reduce overall cholesterol levels and low-density lipoproteins (LDL or bad cholesterol), which are harmful to the heart

- Increase high-density lipoproteins (HDL or good cholesterol), which are beneficial for the heart

- Reduce other harmful lipids (fatty molecules) such as triglycerides and lipoprotein(a)

Any diet should also help keep blood pressure and weight under control. General guidelines for a heart-healthy diet include:

- Make vegetables, fruits, and whole grains the focus of your diet. Examples of whole grains include brown rice, quinoa, oats, barley, and millet.

- Include low-fat dairy products, poultry, fish, legumes (beans), nontropical vegetable oils, and nuts.

- Limit intake of sweets, sugar-sweetened beverages, and red meats.

- Avoid saturated fats (found mostly in animal products) and trans fatty acids (found in hydrogenated fats and many commercial baked products and fast-foods). Choose unsaturated fats (particularly omega-3 fatty acids found in vegetable and fish oils).

- When selecting proteins, choose soy protein, poultry, and fish over meat.

- Weight control, quitting smoking, and exercise are essential companions of any diet program.

Vitamins

While vitamin deficiencies may be associated with PAD and heart disease, vitamin supplements have not been proven to reduce the risk for heart-related conditions. Low levels of vitamin D are linked to an increased risk of PAD, and many older Americans are deficient in this vitamin. More research is needed to determine if vitamin D supplements protect against PAD.

Deficiencies in the B vitamins folate and B12 are associated with elevated levels of homocysteine, an amino acid that may be a marker for increased risk for heart disease and PAD. However, while vitamin supplementation lowers homocysteine levels, it has no effect on heart disease outcomes. Similarly, vitamin E and other multivitamin supplements do not help PAD symptoms.

Herbs and Supplements

Generally, manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need FDA approval to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been a number of reported cases of serious and even lethal side effects from herbal products. Always check with your health care provider before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements.

Ginkgo biloba is an herbal remedy reported to have blood-thinning properties. However, studies have shown it does not provide any benefit for people with PAD or intermittent claudication. Although the risks for ginkgo appear to be low, there is an increased risk for bleeding at high doses and harmful interaction with high doses of anti-clotting medications. This is particularly important because people with PAD often use these types of medications. Commercial ginkgo preparations have also been reported to contain colchicine, a chemical that can be harmful in pregnant women and people with kidney or liver problems.

Medications

Medications for PAD help prevent blood clots and reduce the risk for heart attack and stroke.

Aspirin and Other Antiplatelet Drugs

Antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin prevent blood clots. Most people with peripheral artery disease receive antiplatelet medication. For the most part, this recommendation is made to prevent future death from heart attack or stroke. Antiplatelet drugs may or may not provide benefit for PAD symptoms and progression.

Aspirin (75 to 100 mg per day) is usually the recommended first-line choice to prevent heart attack or stroke in people with PAD. It is also recommended to be started before any surgical procedure and continued afterwards without stopping or bypasses on arteries below the inguinal area. However, recent studies have indicated that aspirin may not have much benefit in preventing heart attack or stroke in people who have PAD without also having heart disease.

Clopidogrel (Plavix, generic) (75 mg per day) is another antiplatelet drug that is sometimes used as an alternative to aspirin. Clopidogrel plus aspirin is recommended for people after bypass graft surgery that uses a man-made or prosthetic graft performed on arteries below the knee.

Vorapaxar (Zontivity) is a new type of antiplatelet drug approved to lower risk of heart attack, stroke, or heart disease death for people who have peripheral artery disease or those who have had a heart attack. It is the first in a new class of drugs called protease-activated receptor-1 (PAR-1) antagonists. People who have had a stroke should not use this drug because the risk of bleeding is too great.

Research indicates that adding an anticoagulant drug, such as warfarin (Coumadin, generic), to antiplatelet therapy does not help prevent heart complications of PAD, and can increase the risks for life-threatening bleeding. Coumadin may be used in some people after bypass surgery that utilizes a venous graft, if concern for clotting is high.

All antiplatelet drugs can increase the risks for bleeding.

Statin Drugs

Statins are the most common type of medication used to help lower LDL cholesterol and improve lipid profiles. Cholesterol management is a very important part of PAD treatment. Current guidelines recommend statin therapy for all people with PAD.

Statin drugs include:

- Lovastatin (Mevacor, generic)

- Pravastatin (Pravachol, generic)

- Simvastatin (Zocor, generic)

- Fluvastatin (Lescol)

- Atorvastatin (Lipitor, generic)

- Rosuvastatin (Crestor)

- Pitavastatin (Livalo)

ACE Inhibitors

ACE inhibitors are a type of drug used to treat high blood pressure. These drugs block the effects of the angiotensin-renin-aldosterone system, which is associated with many harmful effects on the heart and blood vessels. They are important drugs for patients with PAD and diabetes who also have high blood pressure.

In addition to heart protection, ACE inhibitors may help reduce pain that patients experience when walking. The ACE inhibitor ramipril (Altace, generic) is often specifically recommended for people with symptomatic peripheral artery disease. Studies indicate that in addition to reducing the risk of cardiovascular events, ramipril may help improve walking ability and quality of life in people with intermittent claudication.

ACE inhibitors include:

- Ramipril (Altace, generic)

- Captopril (Capoten, generic)

- Enalapril (Vasotec, generic)

- Quinapril (Accupril, generic)

- Benazepril (Lotensin, generic)

- Perindopril (Aceon, generic)

- Lisinopril (Prinivil, Zestril, generic)

Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors for Intermittent Claudication

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors are drugs that help improve blood flow. They may be prescribed to treat intermittent claudication.

CilostazolCilostazol (Pletal, generic) is used to treat disabling intermittent claudication. A number of studies have reported that the drug helps improve walking distance and quality of life. It also helps improve HDL and triglyceride levels. Cilostazol works better than pentoxifylline, the first drug approved for claudication. However, it is expensive, and currently recommended only for people with moderate-to-severe intermittent claudication who do not respond to aspirin or less costly treatments.

Common side effects include headache, swelling in the limbs, and stomach problems such as diarrhea and flatulence (gas). It does not appear to have bad effects on the liver or kidney. Similar drugs can have serious side effects in patients with heart failure, so patients with heart failure should avoid cilostazol.

PentoxifyllinePentoxifylline (Trental, generic) reduces the sticky properties of blood cells, improving blood flow. It is approved in the United States for managing claudication, although doctors do not recommend its routine use. Studies regarding the drug's effectiveness have been mixed. Some studies have reported a small effect on walking ability; another found the drug significantly improved walking distance. Other research has found that the drug does not work any better than a dummy pill (placebo). The most common side effects include headache, nausea, heartburn, flatulence (gas), dizziness, blurred vision, and flushing.

Surgery

In severe cases of PAD, surgery may be needed to open blocked blood vessels. Many different types of surgical procedures can be performed. They include open bypass procedures, which connect an artery before the location of the obstruction to an artery below the obstruction, or minimally invasive endovascular techniques such as angioplasty and stenting. The location of the lesions and how many other risk factors and illnesses patients have often determine which procedure is chosen.

Surgery is generally performed for claudication that has become disabling despite full medical and exercise therapy. Surgery may also be necessary for patients with rest pain, and to save a limb when a person develops critical limb ischemia and is in danger of amputation.

A grading system helps classify peripheral artery disease in patients in a manner that suggests who will do better with any type of surgery, as well as whether bypass surgery or percutaneous angioplasty and stent is a better choice. The system takes into consideration which arteries are involved, as well as how many arteries and how many parts of an individual artery are narrowed. The age of the patient and how disabled they are by other medical problems must also be considered. Before any procedures, all patients must be evaluated further risk of having heart complications or a stroke during any surgical procedure.

Leg Bypass Surgery

For many years, leg bypass surgery was the main type of surgery used for extensive PAD. This procedure involves the creation of a tube (graft) that acts as a new blood vessel. Grafts can be made from synthetic material (artificial vein) or from a vein taken from a different location in the person's leg (natural vein). The graft reroutes blood flow in the leg, around the blocked artery. Possible bypass connections between arteries include aorta to iliac arteries, aorta to femoral arteries, and bypass between the femoral artery and popliteal, tibial, and peroneal arteries.

Artificial veins tend to pose a much higher risk for blood clots, and the consequences of re-blockage are must more severe than when the natural vein recloses. To keep the artificial vein open, oral anti-clotting drugs such as aspirin or warfarin may be used. (Such drugs do not work with natural vein bypass.)

In general, less invasive procedures, such as balloon angioplasty and stenting, are now more frequently performed.

Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty

Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) is an approach that has several variations. The object of the procedure is to open the blocked blood vessels that are causing intermittent claudication. Angioplasty is being increasingly used in place of leg bypass surgery, especially in patients who have other medical conditions.

Although not exclusively, percutaneous treatment is more likely to be recommended for those with focal narrowing of the aorta or iliac arteries, such as the common and external iliac arteries.

The PTA procedure requires only a local anesthetic. People can return to normal activity in 24 to 48 hours. Complication rates are low. The effects are not permanent, but the procedure can be repeated with minimal risk.

Anticoagulants (such as warfarin or heparin) and antiplatelets (such as aspirin) may be used to prevent blood clots occurring during surgery. All of these drugs increase the risk for bleeding.

Thrombolytic drugs such as alteplase (Activase) and reteplase (Retavase) may be used intravenously before, during, or after angioplasty if a blood clot is present. Such drugs are commonly called "clot-busters." They break up existing clots, and may be used in cases of acute vascular occlusion (the sudden development of a blood clot).

Balloon AngioplastyThe standard procedure is balloon angioplasty. A thin tube is inserted through an artery in the groin and passed through the blocked artery. A wire is threaded through the tube. A deflated balloon is passed over the wire to the blockage. When inflated, it opens the artery.

Because balloon angioplasty poses a risk for reclosure of the artery, various other procedures are used or are being investigated.

StentingRe-blockage of the blood vessels from blood clotting, even long after surgery, is a major complication. To help prevent this complication, and repeat surgery, a tiny expandable metal mesh tube (stent) is often used along with angioplasty. However, even with stents, some people experience new blockages within a year of surgery. Some angioplasties are performed with a drug-eluting stent, which is coated with the drug paclitaxel to help prevent blockages from occurring in the stents.

Drug-eluting stents may not be recommended for people who had recent heart surgery, or women who are nursing or pregnant. People who receive a drug-eluting stent may need to take blood thinning drugs for at least several months.

Resources

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute -- www.nhlbi.nih.gov

- American Heart Association -- www.heart.org

- American College of Cardiology -- www.acc.org

- American Diabetes Association -- www.diabetes.org

- Vascular Cures -- www.vascularcures.org

- Society of Interventional Radiology -- www.sirweb.org

References

Aboyans V, Criqui MH, Abraham P, et al. Measurement and interpretation of the ankle-brachial index: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;126(24):2890-2909. PMID: 23159553 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23159553/.

Aday AW, Lawler PR, Cook NR, Ridker PM, Mora S, Pradhan AD. Lipoprotein particle profiles, standard lipids, and peripheral artery disease incidence - prospective data from the Women's Health Study. Circulation. 2018; pii: CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035432. PMID: 30021845 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30021845/.

Alonso-Coello P, Bellmunt S, McGorrian C, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in peripheral artery disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e669S-e690S. PMID: 22315275 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22315275/.

Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e596-e646. PMID: 30879355 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30879355/.

Bonaca MP, Creager MA. Peripheral artery diseases. In: Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Braunwald E, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 64.

Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2960-2984. PMID: 24239922 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24239922/.

Fakhry F, Spronk S, van der Laan L, et al. Endovascular revascularization and supervised exercise for peripheral artery disease and intermittent claudication: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(18):1936-1944. PMID: 26547465 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26547465/.

Firnhaber JM, Powell CS. Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(6):362-369. PMID: 30874413 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30874413/.

Fleg JL, Forman DE, Berra K, et al. Secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in older adults: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128(22):2422-2446. PMID: 24166575 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24166575/.

Fowkes FG, Aboyans V, Fowkes FJ, McDermott MM, Sampson UK, Criqui MH. Peripheral artery disease: epidemiology and global perspectives. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14(3):156-170. PMID: 27853158 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27853158/.

Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135(12):e726-e779. PMID: 27840333 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27840333/.

Hennion DR, Siano KA. Diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial disease. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(5):306-310. PMID: 24010393 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24010393/.

Hirsch AT, Allison MA, Gomes AS, et al. A call to action: women and peripheral artery disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(11):1449-1472. PMID: 22343782 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22343782/.

Joosten MM, Pai JK, Bertoia ML, et al. Associations between conventional cardiovascular risk factors and risk of peripheral artery disease in men. JAMA. 2012;308(16):1660-1667. PMID: 23093164 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23093164/.

Mackman N, Spronk HMH, Stouffer GA, Ten Cate H. Dual anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy for coronary artery disease and peripheral artery disease patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38(4):726-732. PMID: 29449336 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29449336/.

Morley RL, Sharma A, Horsch AD, Hinchliffe RJ. Peripheral artery disease. BMJ. 2018;360:j5842. PMID: 29419394 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29419394/.

Murphy TP, Cutlip DE, Regensteiner JG, et al. Supervised exercise, stent revascularization, or medical therapy for claudication due to aortoiliac peripheral artery disease: the CLEVER study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(10):999-1009. PMID: 25766947 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25766947/.

Rooke TW, Hirsch AT, Misra S, et al. Management of patients with peripheral artery disease (compilation of 2005 and 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline Recommendations): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(14):1555-1570. PMID: 23473760 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23473760/.

Shu J, Santulli G. Update on peripheral artery disease: epidemiology and evidence-based facts. Atherosclerosis. 2018; 275:379-381. PMID: 29843915 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29843915/.

Smith SC Jr, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation endorsed by the World Heart Federation and the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(23):2432-2446. PMID: 22055990 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22055990/.

Society for Vascular Surgery Lower Extremity Guidelines Writing Group; Conte MS, Pomposelli FB, et al. Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines for atherosclerotic occlusive disease of the lower extremities: management of asymptomatic disease and claudication. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61(3 Suppl):2S-41S. PMID: 25638515 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25638515/.

Stoekenbroek RM, Boekholdt SM, Fayyad R, et al. High-dose atorvastatin is superior to moderate-dose simvastatin in preventing peripheral arterial disease. Heart. 2015;101(5):356-362. PMID: 25595417 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25595417/.

Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2889-2934. PMID: 24239923 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24239923/.

US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for peripheral artery disease and cardiovascular disease risk assessment with the ankle-brachial index: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;320(2):177-183. PMID: 29998344 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29998344/.

Valentine EA, Ochroch EA. 2016 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: perioperative implications. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2017;31(5):1543-1553. PMID: 28826846 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28826846/.

Wardle BG, Ambler GK, Radwan RW, Hinchliffe RJ, Twine CP. Atherectomy for peripheral arterial disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;9:CD006680. PMID: 32990327 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32990327/.

Review Date: 12/29/2020

Reviewed By: Deepak Sudheendra, MD, RPVI, FSIR, Director of DVT & Complex Venous Disease Program, Assistant Professor of Interventional Radiology & Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, with an expertise in Vascular Interventional Radiology & Surgical Critical Care, Philadelphia, PA. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.