Heart bypass surgery - discharge

Off-pump coronary artery bypass - discharge; OPCAB - discharge; Beating heart surgery - discharge; Bypass surgery - heart - discharge; CABG - discharge; Coronary artery bypass graft - discharge; Coronary artery bypass surgery - discharge; Coronary bypass surgery - discharge; CAD - bypass discharge; Coronary artery disease - bypass dischargeHeart bypass surgery creates a new route, called a bypass, for blood and oxygen to go around one or more blockages in the coronary arteries to reach your heart muscle. The surgery is used to treat coronary heart disease. This article discusses what you need to do to care for yourself when you leave the hospital.

When You're in the Hospital

Your surgeon took a vein or artery from another part of your body to create a detour, or bypass, around an artery that was blocked and could not bring enough blood to your heart muscle.

Your surgery was done through an incision (cut) in your chest. If the surgeon went through your breastbone, the surgeon repaired it with wire and a metal plate, and your skin was closed with stitches. You also had an incision made in your leg or arm, where the vein was taken to be used for the bypass.

What to Expect at Home

After surgery, it takes 4 to 6 weeks to completely heal and start feeling better. It is normal to:

- Have pain in your chest area around your incision.

- Have a poor appetite for 2 to 4 weeks.

- Have mood swings and feel depressed.

- Have swelling in the leg that the vein graft was taken from.

- Feel itchy, numb, or tingly around the incisions on your chest and leg for 6 months or more.

- Have trouble sleeping at night.

- Be constipated from pain medicines.

- Have trouble with short-term memory or feel confused ("fuzzy-headed").

- Be tired or not have much energy.

- Have some shortness of breath. This may be worse if you also have lung problems. Some people may use oxygen when they go home.

- Have weakness in your arms for the first month.

Self-care

You should have someone stay with you in your home for at least the first 1 to 2 weeks after surgery.

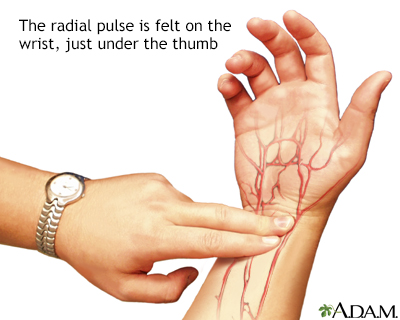

Learn how to check your pulse, and check it every day.

Do the breathing exercises you learned in the hospital for 4 to 6 weeks.

Shower every day, washing the incision gently with soap and water. DO NOT swim, soak in a hot tub, or take baths until your incision is completely healed. Follow a heart-healthy diet.

If you feel depressed, talk with your family and friends. Ask your surgeon or health care provider about getting help from a counselor.

Continue to take all your medicines for your heart, diabetes, high blood pressure, or any other conditions you have.

- Do not stop taking any medicine without first talking with your provider.

- Your provider may recommend antiplatelet (blood-thinning) drugs such as aspirin, clopidogrel (Plavix), prasugrel (Effient), or ticagrelor (Brilinta) to help keep your artery graft open.

Aspirin

Current guidelines recommend that people with coronary artery disease (CAD) receive antiplatelet therapy with either aspirin or clopidogrel. Aspirin ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark ArticleClopidogrel

Platelets are small particles in your blood that your body uses to form clots and stop bleeding. If you have too many platelets or your platelets st...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - If you are taking a blood thinner, such as warfarin (Coumadin), you may need to have extra blood tests to make sure your dose is correct.

Know how to respond to angina symptoms.

Know how to respond to angina symptoms

Angina is a type of chest discomfort due to poor blood flow through the blood vessels of the heart muscle. This article discusses how to care for yo...

Activity

Stay active during your recovery, but start slowly.

- Do not stand or sit in the same spot for too long. Move around a little bit.

- Walking is a good exercise for the lungs and heart after surgery. Do not be concerned about how fast you are walking. Take it slow.

- Climbing stairs is OK, but be careful. Balance may be a problem. Rest halfway up the stairs if you need to.

- Light household chores, such as setting the table, folding clothes, walking, and climbing stairs, should be OK.

- Slowly increase the amount and intensity of your activities over the first 3 months.

- Do not exercise outside when it is too cold or too hot.

- Stop if you feel short of breath, dizzy, or any pain in your chest. Do not do any activity or exercise that causes pulling or pain across your chest, such as using a rowing machine or weight lifting.

- Keep your incision areas protected from the sun to avoid sunburn.

Ask your surgeon when driving is OK. Do not expect to drive for at least 4 to 6 weeks after your surgery. The twisting involved in turning the steering wheel may pull on your incision. Ask your surgeon when you may return to work, and expect to be away from work for about 6 to 8 weeks.

Do not travel for at least 2 to 4 weeks. Ask your surgeon when travel is OK. Also, ask your surgeon before starting sexual activity again. Most of the time it is OK after 4 weeks.

You may be referred to a formal cardiac rehabilitation program. You will get information and counseling regarding activity, diet, and supervised exercise.

Wound Care

For the first 6 weeks after your surgery, you must be careful about using your arms and upper body when you move.

- Do not reach backward.

- Do not let anyone pull on your arms for any reason -- for instance, if they are helping you move around or get out of bed.

- Do not lift anything heavier than 5 to 7 pounds (2 to 3 kilograms).

- Do not do even light housework for at least 2 to 3 weeks.

- Check with your provider before using your arms and shoulder more.

Brushing your teeth is OK, but do not do other activities that keep your arms above your shoulders for any period of time. Keep your arms close to your sides when you are using them to get out of bed or a chair. You may bend forward to tie your shoes. Always stop if you feel pulling on your breastbone.

Your surgeon will tell you how to take care of your chest wound. You will likely be asked to clean your surgical cut every day with soap and water, and gently dry it. Do not use any creams, lotions, powders, or oils unless your provider tells you it is OK.

Clean your surgical cut every day with ...

An incision is a cut through the skin made during surgery. It is also called a surgical wound. Some incisions are small. Others are very long. Th...

If you had a cut or incision on your leg:

- Keep your legs raised when sitting.

- Wear elastic TED hose for 2 to 3 weeks until the swelling goes away and you are more active.

When to Call the Doctor

Contact your surgeon or provider if:

- You have chest pain or shortness of breath that does not go away when you rest.

- Your pulse feels irregular -- it is very slow (fewer than 60 beats a minute) or very fast (over 100 to 120 beats a minute).

- You have dizziness, fainting, or you are very tired.

- You have a severe headache that does not go away.

- You have a cough that does not go away.

- You are coughing up blood or yellow or green mucus.

- You have problems taking any of your heart medicines.

- Your weight goes up by more than 2 pounds (1 kilogram) in a day for 2 days in a row.

- Your wound changes. It is red or swollen, it has opened, or there is more drainage coming from it.

- You have chills or a fever over 101°F (38.3°C).

References

Morrow DA, de Lemos J. Stable ischemic heart disease. In: Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Bhatt DL, Solomon SD, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 40.

Omer S, Bakaeen FG. Acquired heart disease: coronary insufficiency. In: Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. 21st ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2022:chap 60.

Virani SS, Newby LK, Arnold SV, et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline for the management of patients with chronic coronary disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2023;148(9):e9-e119. PMID: 37471501 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37471501/.

-

Taking your carotid pulse - illustration

The carotid arteries take oxygenated blood from the heart to the brain. The pulse from the carotids may be felt on either side of thefront of the neck just below the angle of the jaw. This rhythmic beat is caused by varying volumes of blood being pushed out of the heart toward the extremities.

Taking your carotid pulse

illustration

-

How to take your wrist pulse - illustration

How to take your pulse. 1. Place the tips of your index and middle finger on the inside of your wrist below the base of your thumb. 2. Press lightly. You will feel the blood pulsing beneath your fingers. 3. Use a watch or clock with a second hand. Count the beats you feel for 1 minute. Or count the beats for 30 seconds and multiply by 2. This is also called your pulse rate.

How to take your wrist pulse

illustration

-

Taking your carotid pulse - illustration

The carotid arteries take oxygenated blood from the heart to the brain. The pulse from the carotids may be felt on either side of thefront of the neck just below the angle of the jaw. This rhythmic beat is caused by varying volumes of blood being pushed out of the heart toward the extremities.

Taking your carotid pulse

illustration

-

How to take your wrist pulse - illustration

How to take your pulse. 1. Place the tips of your index and middle finger on the inside of your wrist below the base of your thumb. 2. Press lightly. You will feel the blood pulsing beneath your fingers. 3. Use a watch or clock with a second hand. Count the beats you feel for 1 minute. Or count the beats for 30 seconds and multiply by 2. This is also called your pulse rate.

How to take your wrist pulse

illustration

Review Date: 7/14/2024

Reviewed By: Michael A. Chen, MD, PhD, Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Harborview Medical Center, University of Washington Medical School, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.