| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hyperemesis Gravidarum

Hyperemesis gravidarum is the term used for persistent nausea and vomiting during pregnancy.

While over half of all pregnant women experience some form of morning sickness, only 1.5% to 2% suffer from hyperemesis gravidarum, a much more serious condition. Often leading to dehydration and malnutrition, hyperemesis gravidarum sends more than 50,000 pregnant women to the hospital each year. While more common in the first trimester, it often continues throughout the entire pregnancy. Fortunately, if diagnosed in time and treated properly, it presents little risk to you or your baby.

The exact cause of hyperemesis gravidarum is unknown, but some factors may include:

- High levels of hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). Levels of this pregnancy hormone rise quickly during the early stages of pregnancy and may trigger the part of the brain that controls nausea and vomiting.

- Increased estrogen levels. This hormone also affects the part of the brain that controls nausea and vomiting.

- Gastrointestinal changes. During your entire pregnancy the digestive organs displace to make room for the growing fetus. This may result in acid reflux and the stomach emptying more slowly, which can cause nausea and vomiting.

- Psychological factors. Stress can often make you physically ill. The anxiety that can accompany a pregnancy may trigger acute morning sickness.

- High-fat diet. Recent research shows that women with a high-fat diet are at a much greater risk for developing hyperemesis gravidarum. Their risk increases five times for every additional 15 grams of saturated fat (such as a quarter-pound cheeseburger) they eat each day.

- Helicobacter pylori. A research study in Obstetrics &Gynecology reported that 90% of pregnant women with hyperemesis gravidarum are also infected with this bacterium, which may sometimes cause stomach ulcers.

Women at increased risk for hyperemesis include those in their first pregnancy, carrying more than one baby, under the age of 24, or carrying a female fetus. Women with a prior history of nausea in pregnancy and those who are obese are also at increased risk.

How Do I Know Have It?

The symptoms are unmistakable and sometimes even crippling, including:

- Severe nausea.

- Persistent, excessive vomiting or the urge to vomit. Vomiting is considered excessive if it occurs more than three or four times per day and prevents you from keeping down any food or fluids for a period of 24 hours.

- Weight loss of 5 or more pounds over a 1-2 week period. *

- Lightheadedness or fainting. *

- Infrequent urination. *

- Pale skin.

- Jaundice. *

- Dehydration. *

*(These symptoms result from malnutrition and dehydration brought on by excessive vomiting.)

Your health care provider may perform several tests to rule out other possible causes, including:

- Gastrointestinal problems.

- Thyroid problems and other metabolic disorders.

- Liver problems.

- Neurological disorders.

- Molar pregnancy.

- HELLP syndrome, in cases where the condition appears later in the pregnancy.

Your health care provider may also check for signs of dehydration with urine tests and blood tests.

How Can I Treat It?

It is important to contact your health care provider if you are experiencing severe nausea and vomiting. If properly treated, there should be no serious complications for you or your baby. Your health care provider can tell you whether your case is mild or severe. If it's mild, you should change your diet by eating more protein and complex carbohydrates, such as nuts, cheese and crackers, and milk. It's best to eat these foods in small portions, several times throughout the day. You should also avoid eating fatty foods, drink plenty of water, and get as much rest as possible. (For more suggestions, see our morning sickness article). Your doctor may also recommend taking antacids and an antiemetic (anti-vomiting) medication.

Medications your doctor may prescribe for severe cases include:

- Antihistamines, which help ease nausea and motion sickness.

- Vitamin B6, which helps ease nausea (if you're unable to take it orally your doctor can give you an injection).

- Phenothiazine, which helps ease nausea and vomiting.

- Metoclopramide, which helps increase the rate that the stomach moves food into the intestines.

- Antacids, which can absorb stomach acid and help prevent acid reflux.

Severe cases of hyperemesis gravidarum require hospitalization. Once at the hospital, you may receive intravenous fluids, glucose, electrolytes, and, occasionally, vitamins and other nutritional supplements. Your vitamin levels may also be monitored since women suffering from hyperemesis gravidarum are often deficient in thiamine, riboflavin, vitamin B6, vitamin A, and retinol-binding proteins. Remember, pregnant women need to maintain a much higher level of calories, protein, iron, and folate than nonpregnant women. Your health care provider will talk to you about the sufficient levels and how to maintain them.

Anti-nausea drugs and sedatives may be given, and you will be encouraged to rest. After receiving intravenous (IV) fluids for 24 to 48 hours, you may be ready to eat a clear liquid diet and then move on to eating several small meals a day. You will be monitored by your health care provider after you leave the hospital, and be readmitted if problems continue or recur.

Women with hyperemesis gravidarum are often encouraged to work with a counselor since emotional problems may not only contribute to this condition, but may result from it as well.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can I take steps to prevent this from happening to me?

A: Women who start taking prenatal vitamins early in pregnancy seem to be at lower risk of hyperemesis. Once symptoms start, it’s important to get care as soon as possible, so that the problem doesn’t progress.

Q: I am suffering from a mild case of hyperemesis gravidarum. Am I going to be sick like this my whole pregnancy?

A: For most women, nausea and vomiting are worse between six and 12 weeks gestation, and will subside and even vanish by the second half of pregnancy.

Q: Are there any serious complications with hyperemesis gravidarum?

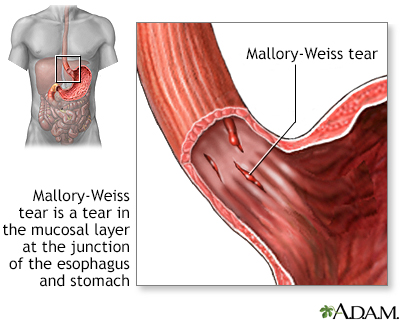

A: Complications are extremely rare, but do happen. Mallory-Weiss tears (tears to the cardiac part of the stomach from excessive vomiting) and Wernicke's encephalopathy (a syndrome related to thiamin deficiency that may cause disorientation, confusion, and coma) have been reported in some rare cases. Miscarriage is extremely rare. In fact, women with bad nausea and vomiting have lower rates of miscarriage than those who breeze through early pregnancy.

|

Review Date:

12/9/2012 Reviewed By: Irina Burd, MD, PhD, Maternal Fetal Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. |