Newborn jaundice

Jaundice of the newborn; Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia; Bili lights - jaundice; Infant - yellow skin; Newborn - yellow skinNewborn jaundice occurs when a baby has a high level of bilirubin in the blood. Bilirubin is a yellow substance that the body creates when it replaces old red blood cells. The liver helps break down the substance so it can be removed from the body in the stool.

A high level of bilirubin makes a baby's skin and whites of the eyes look yellow. This is called jaundice.

Causes

It is normal for a baby's bilirubin level to be a bit high after birth.

When the baby is growing in the mother's womb (uterus), the placenta removes bilirubin from the baby's body. The placenta is the organ that grows during pregnancy to feed the baby. After birth, the baby's liver starts doing this job. But, it may take some time for the baby's liver to be able to do this efficiently.

Most newborns have some jaundice. This is called physiological jaundice. It is usually noticeable when the baby is 2 to 4 days old. Most of the time, it does not cause problems and goes away within 2 weeks.

Two types of jaundice may occur in newborns who are breastfed. Both types are usually harmless.

- Breastfeeding jaundice is seen in breastfed babies during the first week of life. It is more likely to occur when babies do not nurse well or the mother's milk is slow to come, leading to dehydration.

Dehydration

Dehydration occurs when your body does not have as much water and fluids as it needs. Dehydration can be mild, moderate, or severe, based on how much...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Breast milk jaundice may appear in some healthy, breastfed babies after day 7 of life. It is likely to peak during weeks 2 and 3, but may last at low levels for a month or more. The problem may be due to how substances in the breast milk affect the breakdown of bilirubin in the liver. Breast milk jaundice is different from breastfeeding jaundice.

Severe newborn jaundice may occur if the baby has a condition that increases the number of red blood cells that need to be replaced in the body, such as:

- Abnormal blood cell shapes (such as sickle cell anemia)

Sickle cell anemia

Sickle cell disease is a disorder passed down through families. The red blood cells that are normally shaped like a disk take on a sickle or crescen...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Blood type mismatch between the mother and baby (Rh incompatibility or ABO incompatibility)

ABO incompatibility

A, B, AB, and O are the 4 major blood types. The types are based on small substances (molecules) on the surface of the blood cells. When people who ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Bleeding underneath the scalp (cephalohematoma) caused by a difficult delivery

- Higher levels of red blood cells, which is more common in small-for-gestational age (SGA) babies and some twins

- Infection

- Lack of certain important proteins, called enzymes

Enzymes

Enzymes are complex proteins that cause a specific chemical change. For example, they can help break down the foods we eat so the body can use them....

Read Article Now Book Mark Article

Things that make it harder for the baby's body to remove bilirubin may also lead to more severe jaundice, including:

- Certain medicines

- Infections present at birth, such as rubella, syphilis, and others

Rubella

Congenital rubella is a condition that occurs in an infant whose mother is infected with the virus that causes German measles. Congenital means the ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark ArticleSyphilis

Congenital syphilis is a severe, disabling, and often life-threatening infection seen in infants whose mothers were infected with syphilis and not fu...

Read Article Now Book Mark Article - Diseases that affect the liver or biliary tract, such as cystic fibrosis or hepatitis

Cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis is a disease that causes thick, sticky mucus to build up in the lungs, digestive tract, and other areas of the body. It is one of th...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark ArticleHepatitis

Hepatitis is swelling and inflammation of the liver.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Low blood oxygen level (hypoxia)

- Infections (sepsis)

- Many different genetic or inherited disorders

Babies who are born too early (premature) are more likely to develop jaundice than full-term babies.

Symptoms

Jaundice causes a yellow color of the skin. It usually begins on the face and then moves down to the chest, belly area, legs, and soles of the feet.

Sometimes, infants with severe jaundice may be very tired and feed poorly.

Exams and Tests

Your baby's health care providers will watch for signs of jaundice at the hospital. After the newborn goes home, family members will usually spot the jaundice.

Any infant who appears jaundiced should have bilirubin levels measured right away. This can be done with a blood test.

Many hospitals check total bilirubin levels on all babies at about 24 hours of age. Hospitals use probes that can estimate the bilirubin level just by touching the skin. High readings need to be confirmed with blood tests.

Blood tests

The bilirubin blood test measures the level of bilirubin in the blood. Bilirubin is a yellowish pigment found in bile, a fluid made by the liver. Bi...

Tests that will likely be done include:

-

Complete blood count

Complete blood count

A complete blood count (CBC) test measures the following:The number of white blood cells (WBC count)The number of red blood cells (RBC count)The numb...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Coombs test

Coombs test

The Coombs test looks for antibodies that may stick to your red blood cells and cause red blood cells to die too early.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Reticulocyte count

Reticulocyte count

Reticulocytes are slightly immature red blood cells. A reticulocyte count is a blood test that measures the amount of these cells in the blood....

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Further testing may be needed for babies who need treatment or whose total bilirubin level is rising more quickly than expected.

Treatment

Treatment is not needed most of the time.

When treatment is needed, the type will depend on:

- The baby's bilirubin level

- How fast the level has been rising

- Whether the baby was born early (babies born early are more likely to be treated at lower bilirubin levels)

- How old the baby is

A baby will need treatment if the bilirubin level is too high or is rising too quickly.

A baby with jaundice needs to take in plenty of fluids with breast milk or formula:

- Feed the baby often (up to 12 times a day) to encourage frequent bowel movements. These help remove bilirubin through the stools. Ask your provider before giving your newborn extra formula.

- In rare cases, a baby may receive extra fluids by intravenous (IV).

Intravenous

Dehydration occurs when your body does not have as much water and fluids as it needs. Dehydration can be mild, moderate, or severe, based on how much...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Some newborns need to be treated before they leave the hospital. Others may need to go back to the hospital when they are a few days old. Treatment in the hospital usually lasts 1 to 2 days.

Leave the hospital

Your baby has been treated in the hospital for newborn jaundice. This article tells you what you need to know when your baby comes home.

Sometimes, special blue lights are used on infants whose bilirubin levels are very high. These lights work by helping to break down bilirubin in the skin. This is called phototherapy.

Phototherapy

Bili lights are a type of light therapy (phototherapy) that is used to treat newborn jaundice. Jaundice is a yellow coloring of the skin and eyes. ...

- The infant is placed under these lights in a warm, enclosed bed to maintain a constant temperature.

- The baby will wear only a diaper and special eye shades to protect the eyes.

- Breastfeeding should be continued during phototherapy, if possible.

- In rare cases, the baby may need an IV line to deliver fluids.

If the bilirubin level is not too high or is not rising quickly, you can do phototherapy at home with a fiberoptic blanket, which has tiny bright lights in it. You may also use a bed that shines light up from the mattress.

- You must keep the light therapy on your child's skin and feed your child every 2 to 3 hours (10 to 12 times a day).

- A nurse will come to your home to teach you how to use the blanket or bed, and to check on your child.

- The nurse will return daily to check your child's weight, feedings, skin, and bilirubin level.

- You will be asked to count the number of wet and dirty diapers.

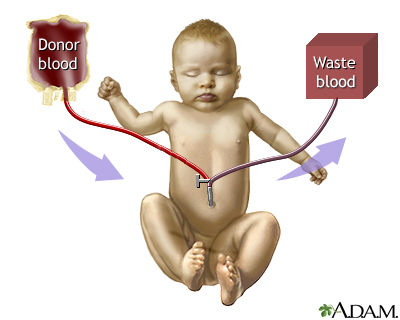

In the most severe cases of jaundice, an exchange transfusion is required. In this procedure, the baby's blood is replaced with fresh blood. Giving IV immunoglobulin to babies who have severe jaundice may also be effective in reducing bilirubin levels.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Newborn jaundice is not harmful most of the time. For most babies, jaundice will get better without treatment within 1 to 2 weeks.

A very high level of bilirubin can damage the brain. This is called kernicterus. The condition is almost always diagnosed before the level becomes high enough to cause this damage. Treatment is usually effective.

Kernicterus

Bilirubin encephalopathy is a rare neurological condition that occurs in some newborns with severe jaundice.

Possible Complications

Rare, but serious complications from high bilirubin levels include:

-

Cerebral palsy

Cerebral palsy

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a group of disorders that involve the brain. This affects nervous system functions, such as movement, learning, hearing, seei...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Deafness

- Kernicterus, which is brain damage from very high bilirubin levels

When to Contact a Medical Professional

All babies should be seen by a provider in the first 5 days of life to check for jaundice:

- Infants who spend less than 24 hours in a hospital should be seen by age 72 hours.

- Infants who are sent home between 24 and 48 hours should be seen again by age 96 hours.

- Infants who are sent home between 48 and 72 hours should be seen again by age 120 hours.

Jaundice is an emergency if the baby has a fever, has become listless, or is not feeding well. Jaundice may be dangerous in high-risk newborns.

Jaundice is generally not dangerous in babies who were born full term and who do not have other medical problems. Contact the infant's provider if:

- Jaundice is severe (the skin is bright yellow)

- Jaundice continues to increase after the newborn visit, lasts longer than 2 weeks, or other symptoms develop

- The feet, especially the soles, are yellow

Talk with your baby's provider if you have questions.

Questions

Newborn jaundice is a common condition. It is caused by high levels of bilirubin (a yellow coloring) in your child's blood. This can make your chil...

Prevention

In newborns, some degree of jaundice is normal and probably not preventable. The risk for serious jaundice can often be reduced by feeding babies at least 8 to 12 times a day for the first several days and by carefully identifying infants at highest risk.

All pregnant women should be tested for blood type and unusual antibodies. If the mother is Rh negative, follow-up testing on the infant's umbilical cord is recommended. This may also be done if the mother's blood type is O positive.

Careful monitoring of all babies during the first 5 days of life can prevent most complications of jaundice. This includes:

- Considering a baby's risk for jaundice

- Checking bilirubin level in the first day or so

- Scheduling at least one follow-up visit the first week of life for babies sent home from the hospital in 72 hours

References

Kaplan M, Wong RJ, Bensen R, Sibley E, Stevenson DK. Neonatal jaundice and liver disease. In: Martin RJ, Fanaroff AA, eds. Fanaroff and Martin's Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2025:chap 95.

Kemper AR, Newman TB, Slaughter JL, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline Revision: Management of hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant 35 or more weeks of gestation. Pediatrics. 2022;150(3):e2022058859. PMID: 35927462 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35927462/.

Kliegman RM. Digestive system disorders. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 22nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2025:chap 134.

Rozance PJ, Wright CJ. The neonate. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al, eds. Gabbe's Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2025:chap 25.

-

Erythroblastosis fetalis - photomicrograph - illustration

Antibodies from an Rh negative mother may enter the blood stream of her unborn Rh positive infant, damaging the red blood cells (RBCs). The infant responds by increasing RBC production and sending out immature RBCs that still have nuclei. This photograph shows normal RBCs, damaged RBCs, and immature RBCs that still contain nuclei.

Erythroblastosis fetalis - photomicrograph

illustration

-

Jaundiced infant - illustration

Newborn jaundice (producing yellow skin) can have many causes, but the majority of these infants have a condition called physiological jaundice, a natural occurrence in the newborn due to the immature liver. This type of jaundice is short term, generally lasting only a few days. Jaundice should be evaluated by a physician until decreasing or normal levels of bilirubin are measured in the blood.

Jaundiced infant

illustration

-

Exchange transfusion - series

Presentation

-

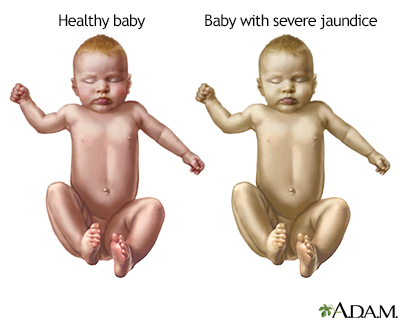

Infant jaundice - illustration

Jaundice is a yellow discoloring of the skin, mucous membranes, and eyes, caused by too much bilirubin (a breakdown product of hemoglobin made by the liver) in the blood. Jaundice is a condition produced when excess amounts of bilirubin circulating in the blood stream dissolve in the subcutaneous fat (the layer of fat just beneath the skin), causing a yellowish appearance of the skin and the whites of the eyes.

Infant jaundice

illustration

-

Erythroblastosis fetalis - photomicrograph - illustration

Antibodies from an Rh negative mother may enter the blood stream of her unborn Rh positive infant, damaging the red blood cells (RBCs). The infant responds by increasing RBC production and sending out immature RBCs that still have nuclei. This photograph shows normal RBCs, damaged RBCs, and immature RBCs that still contain nuclei.

Erythroblastosis fetalis - photomicrograph

illustration

-

Jaundiced infant - illustration

Newborn jaundice (producing yellow skin) can have many causes, but the majority of these infants have a condition called physiological jaundice, a natural occurrence in the newborn due to the immature liver. This type of jaundice is short term, generally lasting only a few days. Jaundice should be evaluated by a physician until decreasing or normal levels of bilirubin are measured in the blood.

Jaundiced infant

illustration

-

Exchange transfusion - series

Presentation

-

Infant jaundice - illustration

Jaundice is a yellow discoloring of the skin, mucous membranes, and eyes, caused by too much bilirubin (a breakdown product of hemoglobin made by the liver) in the blood. Jaundice is a condition produced when excess amounts of bilirubin circulating in the blood stream dissolve in the subcutaneous fat (the layer of fat just beneath the skin), causing a yellowish appearance of the skin and the whites of the eyes.

Infant jaundice

illustration

Review Date: 1/1/2025

Reviewed By: Charles I. Schwartz, MD, FAAP, Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, General Pediatrician at PennCare for Kids, Phoenixville, PA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.